By IndraStra Global News Team

By IndraStra Global News Team

Image Attribute: the Caspian Sea from Space

On August 12, 2018, Azerbaijan, Iran, Kazakhstan, Russian, Iran, and Turkmenistan, agreed in principle by signing the Convention on the Legal Status of the Caspian Sea during the Fifth Caspian Summit, on how to divide up the potentially huge oil and gas resources of the Caspian Sea. The landmark agreement reached at the Kazakh port of Aktau after three decades of argument over how to divide the world’s biggest enclosed body of water. Work on the draft document has continued since 1996, while its draft was agreed by the five nations’ foreign ministers on December 4-5, 2017 in Moscow. The new convention will replace the Soviet-Iranian agreements of 1921 and 1940.

The geopolitical experts are calling this development as a "defining moment in the ongoing, massive drive towards Eurasia integration."

Till before this agreement, the territorial disputes have prevented the exploration of at least 20 billion barrels of oil and more than 6.8 trillion cubic meters of gas, the U.S. Energy Information Administration estimated in 2013. At current market prices, that is several trillion dollars' worths of energy resources; with further exploration, it could turn out to be much more.

Image Attribute: Participants of the Fifth Caspian Summit. From left to right: President of Azerbaijan Ilham Aliev, President of Iran Hassan Rouhani, President of Kazakhstan Nursultan Nazarbaev, President of Russia Vladimir Putin and President of Turkmenistan Gurbanguly Berdymukhammedov / Date: August 12, 2018, Place: Aktau, Kazakhstan, Source: Anadolu Agency.

The Caspian Sea convention has been drawn up in 24 articles with the most important highlights being a ban on the military presence of all foreign countries in the sea and transit of military consignments belonging to foreign countries. Also, it emphasizes that the Caspian Sea belongs to all littoral states, prohibiting establishment and handing over of any kind of military bases to foreign countries.

The Caspian Sea convention has been drawn up in 24 articles with the most important highlights being a ban on the military presence of all foreign countries in the sea and transit of military consignments belonging to foreign countries. Also, it emphasizes that the Caspian Sea belongs to all littoral states, prohibiting establishment and handing over of any kind of military bases to foreign countries.

Caspian Sea: A sea or a lake?

The Caspian Sea is the largest enclosed body (an endorheic basin) of water by area (with no exits to any seas or oceans) located between Europe and Asia. And, is variously classified as the world's largest lake or a full-fledged sea.

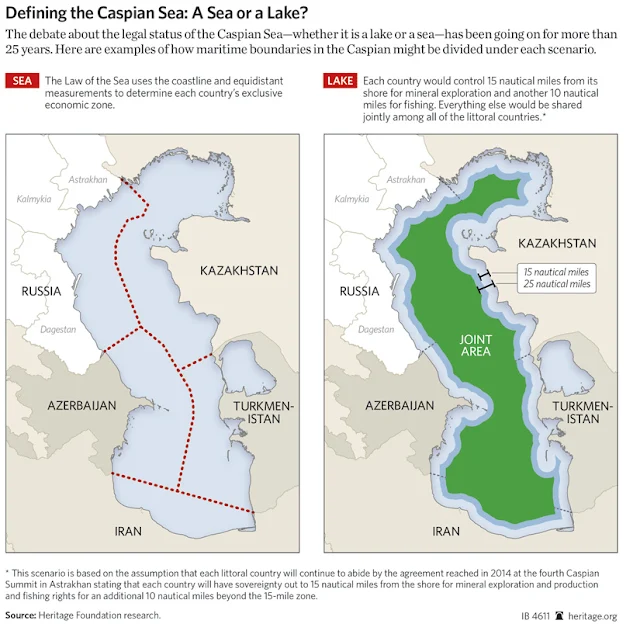

The debate has been going on seen ages. The draft suggests the five littoral states will agree in Aqtau that the Caspian is a sea, but subject to a "special legal status." If the Caspian Sea has been classified as a lake, it would mean the resources of the Caspian should be divided equally among those five countries.

From 1970 until the dissolution of the Soviet Union (USSR) in 1991, the Caspian Sea was divided into subsectors for Azerbaijan (to the west), Russia (to the northwest), Kazakhstan (to the northeast), and Turkmenistan (to the southeast) – all constituent republics of the USSR and Iran (to the south). The division was implemented on the basis of the internationally-accepted median line.

The debate has been going on seen ages. The draft suggests the five littoral states will agree in Aqtau that the Caspian is a sea, but subject to a "special legal status." If the Caspian Sea has been classified as a lake, it would mean the resources of the Caspian should be divided equally among those five countries.

From 1970 until the dissolution of the Soviet Union (USSR) in 1991, the Caspian Sea was divided into subsectors for Azerbaijan (to the west), Russia (to the northwest), Kazakhstan (to the northeast), and Turkmenistan (to the southeast) – all constituent republics of the USSR and Iran (to the south). The division was implemented on the basis of the internationally-accepted median line.

As per the Article 8 of the agreement, the Caspian Sea is regarded as open water, for common use – but the development of seabed reserves will be regulated by separate deals between Caspian nations, in line with international law. The maritime boundaries of each of the five states are already set; 15 nautical miles of sovereign waters, plus a further 10 miles (16 km) for fishing. Beyond that, it’s open water.

Since the beginning of the entire negotiation process, Iran has advocated for an egalitarian approach to delimiting the seabed (each nation would get 20% of the coast), running counter the other countries’ aspirations. But, when Russia concluded its seabed delimitation agreements with Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan in 2001 and 2003, respectively, the parties split their parts using the median line. Article 8's Point 8.1. effectively keeps the delimitation task in the hands of relevant governments, thereby providing a very modest boost to the demarcation of the Southern Caspian. Kindly, do note, the Northern part of the Caspian Sea is fully delimited.

The row between Baku and Teheran revolves around the Araz-Alov-Sharg field (discovered in 1985-1987 by Soviet geologists), the reserves of which are estimated at 300 million tons of oil and 395 bcm of natural gas. Even though the field is only 56 miles (90 km) away from Baku and should seemingly be under Azerbaijan’s grip if one is to draw a straight line from the Azerbaijani-Irani border most of the field ought to be allotted to Iran (the median would keep most of it in Azerbaijan).

Map Attribute: MAP4: Overlapping claims of right to resources in the South Caspian Sea / Source: CIA

The Serdar/Kapaz field (estimated to contain 50 million tons of oil) is the bone of contention between Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan. Considered to be an extension of Azerbaijan’s main oil-producing unit, the Azeri-Chirag-Guneshli field, Baku sees it as an indispensable element in its quest to mitigate decreasing oil output numbers. Geographically, Serdar/Kapaz is closer to Turkmenistan, yet here too Azerbaijan might come out as the ultimate winner. The Apsheron peninsula stretches out some 60km into the Caspian Sea, in effect extending Azerbaijan’s geographical reach. Absent previous demarcation agreements between Baku and Ashgabat, the settlement will once again boil down to getting the angles right, as in the case of Araz-Alov-Sharg.

The most noteworthy element of the agreement is the Article 14, allowing the littoral states to lay undersea pipelines with the approval only of the countries through whose sectors of the sea the pipeline would pass. And, for more than 20 years, Turkmenistan has always wanted to build an energy pipeline to ship its gas across the Caspian Sea to Azerbaijan, where it would be pumped into gas grids leading to Europe via Turkey or the Black Sea. That's how the Trans-Caspian Pipeline (TCP) was envisioned which would run on the seabed of Caspian Sea from Türkmenbaşy to the Sangachal Terminal, where it would connect with the existing pipeline to Erzurum in Turkey, which in turn would be connected to the European Union's Southern Gas Corridor (SGC), thus taking natural gas from Turkmenistan to Central Europe.

Even without an agreement on the Caspian's legal status from all five states, according to energy policy watchers, there was no obstacle to this TCP being built (under the international law) — so long as Turkmenistan and Azerbaijan (both sharing a common median line boundary), through whose territories the pipeline would pass, approved the deal. On the grounds that it poses a potential environmental hazard to the Caspian's unique biosphere, Russia and Iran have opposed the TCP. The claim seemed especially suspect from Russia, since Russia's Gazprom has laid gas pipelines along the Black Sea to Turkey (Blue Stream) and is planning to build another one (TurkStream), and has also completed one pipeline across the Gulf of Finland to Germany (Nord Stream) and is hoping to build another pipeline to Germany (Nord Stream 2).

Some felt Tehran and Moscow's environmental concerns were actually economic concerns, stemming from the desire of each to hinder gas-exporting competitors, in this case, Turkmenistan, from selling to markets in Europe. The European Union supports the construction of the TCP and has included it as a potential part of the EU's SGC strategy.

On the other hand, Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan also have plans to build the Kazakhstan Caspian Transportation System (KCTS) oil pipeline to bring Kazakh oil across the Caspian from the Kazakh port town of Quryq to Baku. If construction of that pipeline goes ahead, it is difficult to imagine that the TCP would not be built.

The Delimitation of the South Caspian Sea

Since the beginning of the entire negotiation process, Iran has advocated for an egalitarian approach to delimiting the seabed (each nation would get 20% of the coast), running counter the other countries’ aspirations. But, when Russia concluded its seabed delimitation agreements with Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan in 2001 and 2003, respectively, the parties split their parts using the median line. Article 8's Point 8.1. effectively keeps the delimitation task in the hands of relevant governments, thereby providing a very modest boost to the demarcation of the Southern Caspian. Kindly, do note, the Northern part of the Caspian Sea is fully delimited.

The row between Baku and Teheran revolves around the Araz-Alov-Sharg field (discovered in 1985-1987 by Soviet geologists), the reserves of which are estimated at 300 million tons of oil and 395 bcm of natural gas. Even though the field is only 56 miles (90 km) away from Baku and should seemingly be under Azerbaijan’s grip if one is to draw a straight line from the Azerbaijani-Irani border most of the field ought to be allotted to Iran (the median would keep most of it in Azerbaijan).

Map Attribute: MAP4: Overlapping claims of right to resources in the South Caspian Sea / Source: CIA

The Serdar/Kapaz field (estimated to contain 50 million tons of oil) is the bone of contention between Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan. Considered to be an extension of Azerbaijan’s main oil-producing unit, the Azeri-Chirag-Guneshli field, Baku sees it as an indispensable element in its quest to mitigate decreasing oil output numbers. Geographically, Serdar/Kapaz is closer to Turkmenistan, yet here too Azerbaijan might come out as the ultimate winner. The Apsheron peninsula stretches out some 60km into the Caspian Sea, in effect extending Azerbaijan’s geographical reach. Absent previous demarcation agreements between Baku and Ashgabat, the settlement will once again boil down to getting the angles right, as in the case of Araz-Alov-Sharg.

The Future of Trans-Caspian Pipeline (TCP)?

The most noteworthy element of the agreement is the Article 14, allowing the littoral states to lay undersea pipelines with the approval only of the countries through whose sectors of the sea the pipeline would pass. And, for more than 20 years, Turkmenistan has always wanted to build an energy pipeline to ship its gas across the Caspian Sea to Azerbaijan, where it would be pumped into gas grids leading to Europe via Turkey or the Black Sea. That's how the Trans-Caspian Pipeline (TCP) was envisioned which would run on the seabed of Caspian Sea from Türkmenbaşy to the Sangachal Terminal, where it would connect with the existing pipeline to Erzurum in Turkey, which in turn would be connected to the European Union's Southern Gas Corridor (SGC), thus taking natural gas from Turkmenistan to Central Europe.

Even without an agreement on the Caspian's legal status from all five states, according to energy policy watchers, there was no obstacle to this TCP being built (under the international law) — so long as Turkmenistan and Azerbaijan (both sharing a common median line boundary), through whose territories the pipeline would pass, approved the deal. On the grounds that it poses a potential environmental hazard to the Caspian's unique biosphere, Russia and Iran have opposed the TCP. The claim seemed especially suspect from Russia, since Russia's Gazprom has laid gas pipelines along the Black Sea to Turkey (Blue Stream) and is planning to build another one (TurkStream), and has also completed one pipeline across the Gulf of Finland to Germany (Nord Stream) and is hoping to build another pipeline to Germany (Nord Stream 2).

Some felt Tehran and Moscow's environmental concerns were actually economic concerns, stemming from the desire of each to hinder gas-exporting competitors, in this case, Turkmenistan, from selling to markets in Europe. The European Union supports the construction of the TCP and has included it as a potential part of the EU's SGC strategy.

On the other hand, Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan also have plans to build the Kazakhstan Caspian Transportation System (KCTS) oil pipeline to bring Kazakh oil across the Caspian from the Kazakh port town of Quryq to Baku. If construction of that pipeline goes ahead, it is difficult to imagine that the TCP would not be built.

With reporting by Asia Times, EurasiaNet, Financial Tribune, OilPrice, RFE/RL, and Reuters