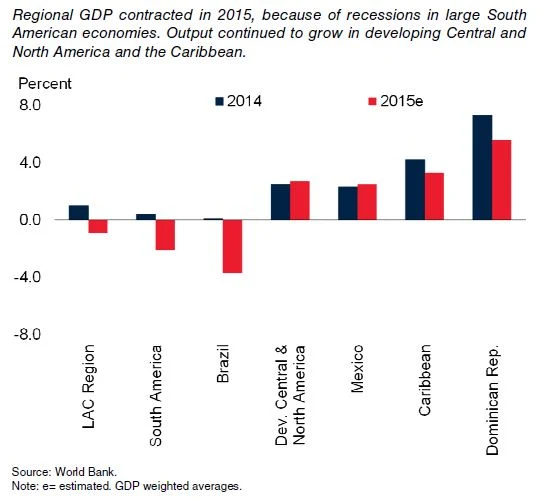

Economic activity in the broader Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) region contracted in 2015. Following three consecutive years of slowing growth, output in the region fell 0.9 percent in 2015,

By World Bank

Economic

activity in the broader Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) region contracted

in 2015. Following three consecutive years of slowing growth, output in the

region fell 0.9 percent in 2015, partly reflecting sharp declines in economic

activity of large regional economies, such as Brazil and the República

Bolivariana de Venezuela (Table 1, Figure 1).

This reduction in output stemmed from a combination of global and domestic factors, particularly the continued slump in commodity prices. Lower crude oil prices – down around 45 percent from 2014 levels – have reduced export earnings and fiscal revenues of regional oil exporters, such as Belize, Colombia, Ecuador, Mexico, and the República Bolivariana de Venezuela.

Figure 1: GDP growth, 2014-2015

Depressed prices of copper, iron ore, gold,

and soy beans have worsened the terms of-trade for commodity exporters, such as

Brazil, Chile, the Dominican Republic, and Peru. A number of governments had to

undertake pro-cyclical fiscal tightening, aggravating the economic slowdown.

Several large South American economies have also been grappling with severe

domestic macroeconomic challenges that have eroded consumer and investor

confidence, further contributing to the regional output decline in 2015.

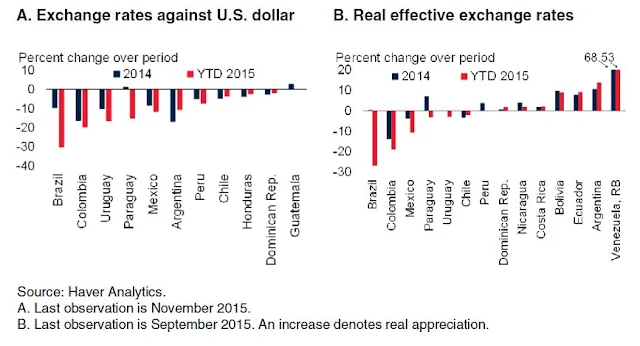

Table 1: Latin America

and the Caribbean forecast summary / Source: World Bank

World Bank

forecasts are frequently updated based on new information and changing (global)

circumstances. Consequently, projections presented here may differ from those

contained in other Bank documents, even if basic assessments of countries’

prospects do not differ at any given moment in time.

a. GDP at market

prices and expenditure components are measured in constant 2010 U.S. dollars.

Excludes Cuba, Granada, and Suriname.

b. Sub-region

aggregate excludes Cuba, Dominica, Granada, Guyana, St. Lucia, St. Vincent and

the Grenadines, and Suriname, for which data limitations prevent the

forecasting of GDP components.

c. Exports and

imports of goods and non-factor services (GNFS).

d. Includes the

following high-income countries: Antigua and Barbuda, Argentina, The Bahamas,

Barbados, Chile, Trinidad and Tobago, Uruguay, and Venezuela, RB.

e. Includes

Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Guyana, Paraguay, Peru,

Uruguay, and Venezuela, RB.

f. Includes

Costa Rica, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, and El Salvador.

g. Includes

Antigua and Barbuda, The Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Dominica, Dominican

Republic, Haiti, Jamaica, St. Lucia, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, and

Trinidad and Tobago.

Output in the

South American sub-region experienced a particularly marked reduction in 2015.[1] With GDP falling in Brazil, Ecuador and the República Bolivariana de Venezuela,

South America saw overall economic growth turn negative, to an estimated -2.1

percent in 2015, after tepid growth in 2014. Investment in Brazil has been

dropping since 2013 due to investors’ loss of confidence, which was exacerbated

in 2015 by the widening investigations into the Petrobras scandal. Monetary and

fiscal tightening, accelerating inflation, and concerns about growing fiscal

deficits also weighed on investment. The República Bolivariana de Venezuela too

is in recession, with very high rates of inflation. Controls that restrict

imports of vital consumer goods and intermediate inputs have curtailed private

consumption and impeded manufacturing. The appreciation of the U.S. dollar has

meant a loss of competitiveness for the fully dollarized Ecuadorean economy.

This, together with lower oil prices, has pushed Ecuador into a recession in

2015. In contrast, Argentina saw activity rebound in 2015.[2] However, the

increase in activity might not be sustainable as it was partly due to a surge

in pre-election public spending, while net exports have been falling and

inflation has been high. Other large economies, particularly commodity

exporters, are continuing to grow at tepid rates.

Despite strong

economic ties to a strengthening United States, developing Central and North

America saw growth rates in 2015 rise modestly from 2014.[3] The sub-region’s

largest economy, Mexico, saw a small pickup in growth in 2015 on the back of

expanding exports to the United States. However, the Mexican economy has been

weighed down by low oil prices and reduced oil production. Lower oil prices

have severely curtailed government revenues, and compelled fiscal

tightening.

Economic growth

in the Caribbean moderated in 2015, with output expanding by 3.3 percent.[4]

The Dominican Republic, the largest economy in the sub-region, experienced a

contraction in mining exports, as prices fell. A surge in investment, including

the construction of new public schools and two new coal-fired power plants,

provided some support to output. In contrast, Jamaica saw growth pick up, amid

increased business and consumer confidence, a successful IMF Extended Fund

Facility program review, and stronger mining output.[5]

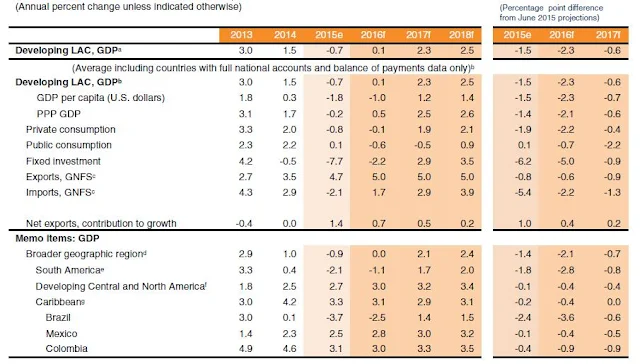

The sharp fall

in commodity prices, predominantly due to well-supplied markets, adversely

affected commodity exporters in LAC. In 2015, prices of agricultural products

declined by about 13 percent, metals by 21 percent, and precious metals by 11

percent from 2014 (Figure 2). Oil prices towards the end of the year were

about 45 percent below 2014 prices. This hurt tax and export revenues, and

exerted pressures on fiscal balances of oil exporters (Belize, Colombia,

Ecuador, Mexico, Venezuela). Similarly, the slump in copper prices, along with

the continued slowdown in major trading partners, dampened investment into the

mining sector, weighing on growth in Chile and Peru.

Figure 2: Commodity Prices

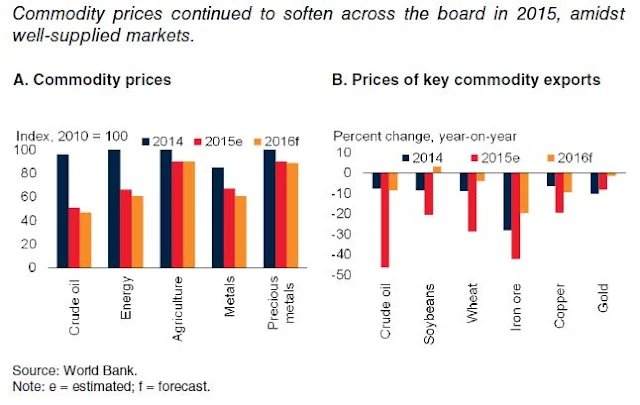

Regional

currencies continued to depreciate in 2015. Commodity exporters in the region

saw large depreciations on account of the continued slump in commodity prices

(Figure 3). At end of October 2015, the currencies of Chile, Colombia,

Mexico and Uruguay depreciated by an average of 13 percent in nominal terms and

around 9 percent in real effective terms with respect to their levels at the

beginning of the year. The Brazilian real saw an exceptionally large

depreciation, due to investor concerns about macroeconomic imbalances and

political uncertainty. The Argentine peso depreciated 27 percent on December

17, 2015 when capital controls were lifted.

Figure 3: Exchange Rates

LAC currencies

continued to depreciate against the U.S. dollar in 2015.The depreciation of the

Brazilian real was particularly steep. Because of high inflation, the real

effective exchange rates of Argentina and the Republica Bolivariana de

Venezuela rose, indicating a loss of cost competitiveness.

Regional export

performance improved in 2015, boosted by weak exchange rates and continued

recoveries in the United States and the Euro Area. Regional export volumes of

goods and services climbed around 5 percent in 2015 after remaining broadly

unchanged in 2014 (Figure 4). Exports in South America expanded by about 4

percent, led by Brazil with a substantially depreciated real. Similarly, with

its close ties with the United States, developing Central and North America

experienced export growth of more than 8 percent. Led by strong tourism demand,

the Caribbean’s exports of goods and services rose almost 5 percent in 2015.

Figure 4: Exports

Regional export

performance improved in 2015, boosted by weak exchange rates and continued

recoveries in the United States and Euro Area.

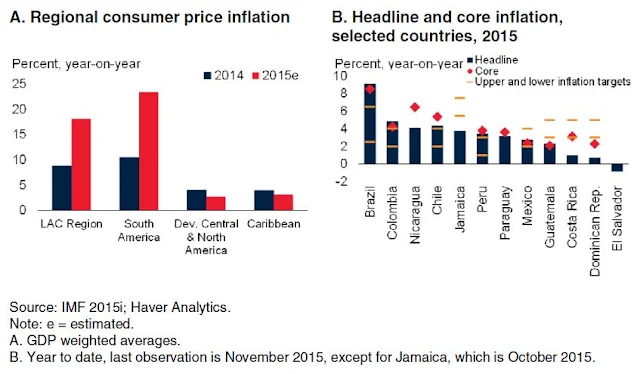

There was a

large divergence in inflation performance across the region. Reduced oil prices

led to lower inflation in developing Central America, North America, and the

Caribbean. For example, despite seeing a 12 percent depreciation of the peso

against the U.S. dollar and being an oil exporter, Mexico’s consumer price

inflation reached historic lows in 2015 (Figure 5). The mild inflation

rates enabled the Banco de México to maintain a record low interest rate of 3

percent for most of 2015 (Figure 6).[6]Inflation pressures in Nicaragua also

eased sharply following a cut in electricity prices in April. El Salvador,

which imports almost all of its oil, saw annual inflation turn negative for

most of 2015. Similarly, consumer prices in Costa Rica fell in the latter half

of 2015, and the central bank further lowered its policy rate to 2.25 percent

in October. Also with low inflation, the Dominican Republic reduced interest

rates and lowered commercial bank reserve requirements in the first half of

2015.

Figure 5: Inflation Rate

Inflation rates are diverging across the countries.

Figure 6: Central bank policy

rates, 2014-2015

Reflecting different

inflation pressures, monetary policies are diverging among countries

In contrast,

consumer price inflation ran at very high rates in Argentina, Brazil, and

especially the República Bolivariana de Venezuela. In Brazil, inflation reached a 12-year high

in the second half of 2015. This was in part due to the one-off effect of a

reduction in subsidies and an increase in administered prices, but the main

reason was higher underlying inflation, as the core inflation accelerated to

above 9 percent. In a series of upward adjustments, the Banco do Brasil raised

policy interest rates to 14.25 percent, a nine-year high. Consumer price

inflation in the República Bolivariana de Venezuela reached well over 100

percent in 2015, as policy has failed to establish an anchor for inflation

expectations.7 Argentina’s.

Inflation in

Colombia is under better control, but has been above the central bank’s 2-4

percent target band since mid-2015. Continued weakness in the peso, along with

a poor harvest of staple crops, contributed to the increase. To guide inflation

back to target, the central bank raised its policy rate in a number of

successive adjustments in the latter half of 2015. Similarly, headline and core

inflation in Peru have been steadily rising and have remained above the

Peruvian central bank’s upper bound target of 3 percent since 2014. This prompted

the central bank to lift the policy rate in September and December.

Fiscal balances

are also on differing paths across LAC. Due to lower commodity and export revenues,

coupled with the slowdown in growth, regional fiscal balances deteriorated, and

the debt/GDP ratio increased in 2015 (Figure 7). Given the large proportion

of major commodity exporters in the sub-region, fiscal balances in South

America as a share of sub-regional GDP are projected to deteriorate by more

than 2 percentage points in 2015. The deficit to GDP ratio for Brazil widened

further, after doubling in 2014. Weak revenues, swelling interest payments, and

losses on central bank dollar swaps, were responsible for the slide. The

Chilean fiscal deficit doubled in 2015. Government revenues have been depressed

by low copper prices. At the same time, the government has boosted public

spending in line with the fiscal stimulus program launched in 2014 to counter slowing

growth. In contrast, Ecuador is projected to see a narrowing of the fiscal

balance in 2015, due to a series of fiscal consolidation measures. Weaker oil

export earnings have led the Ecuadorian government to decrease expenditures by

$2.2 billion in 2015, with cuts almost entirely on capital expenditures.

Figure 7: Fiscal indicators

Fiscal balances are diverging, with

balances deteriorating in South America and improving in the rest of the

region.

Central and

North America, and the Caribbean too saw a narrowing of fiscal deficits in

2015, predominantly due to fiscal consolidation. In Mexico, lower oil prices

and production were offset by a sharp increase in non-oil revenues in the wake

of the tax reform in 2014 and the increase in excise taxes on domestic fuels in

2015. In addition, the government enacted spending cuts equivalent to 0.7

percent of GDP. Supported by the 48-month IMF-supported Extended Fund Facility,

Jamaica introduced new consumption taxes and reduced the public sector wage

bill, as well as sharply lowering gross debt as a share of GDP. After settling

a debt due to the República Bolivariana de Venezuela at a sharp discount, the Dominican

Republic saw a large drop in its debt service costs and registered a

substantial narrowing of its fiscal deficit.

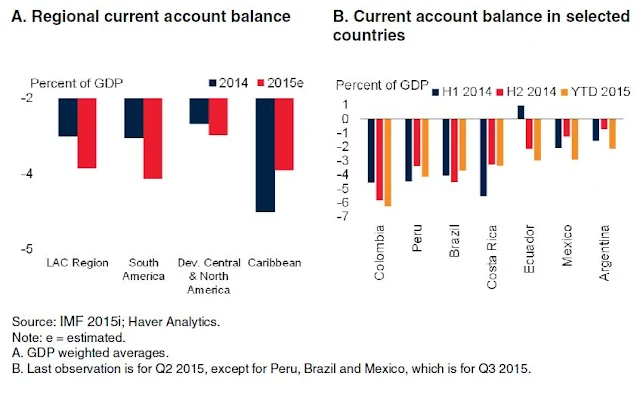

Current account

balances deteriorated throughout most of the region. Despite rising volumes of

total exports, the LAC’s current account deficit as a share of GDP widened to

3.4 percent in 2015 from 2.8 percent in 2014, partly due to reduced export

revenues associated with lower commodity prices (Figure 8). South America’s

current account deficit is estimated to have widened 0.8 percentage point in

2015 to 3.6 percent of GDP. Developing Central and North America saw a smaller

current account deterioration of 0.2 percentage point. As the exception to the

trend, the Caribbean’s deficit narrowed due to elevated tourism receipts.

Colombia saw a current account deficit in the first half of 2015 of more than 6

percent of GDP, due to a plunge in oil export revenues. Similarly, Mexico’s

current account balance suffered from lower oil revenues, owing both to weaker

prices and declining production. However, this was offset by strengthening

export performance of manufactures, which represent a far larger share of

Mexico’s trade and benefited from the weak peso.

Figure 8: Current account balances

Current account balances have

deteriorated in a number of countries.

Gross capital

flows contracted in 2015. Following the sharp slowdown in flows in 2014, gross

capital flows to the region are estimated to have contracted by another 40

percent in 2015 (Figure 9). Brazil and Mexico accounted for around 80

percent of the decline. Weaker-than-expected growth prospects and increased

political uncertainty, especially in Brazil, discouraged investors.

Figure 9: Gross capital

flows

Gross capital

flows declined in 2015.

All three

components of gross capital flows declined in 2015, with equity issuance

contracting the most, falling more than 60 percent. Bond issuance slumped more

than 40 percent from 2014 levels, mainly on account of a $35 billion decline in

new Brazilian bonds. Other economies took advantage of the still favorable

global monetary conditions to put in place refinancing and pre-financing

arrangements. In April, Mexico sold the world’s first 100-year government notes

in euros, as it locked in lower borrowing costs. Colombia issued $4 billion

worth of bonds. Syndicated bank lending dove by 20 percent, reflecting local

banks’ lower funding needs as regional economies cooled.

The large

decline in bond issuance mostly occurred among corporate issuers, particularly Brazilian

corporate deals. Despite its significant appreciation, the U.S. dollar is still

by far the currency of choice for debt issuance in Latin America. From January

to September 2015, over 80 percent of bonds issued were denominated in U.S.

dollars, slightly higher than the same period a year ago.

Sources: Global Economic Prospect 2016 / Download The

Report - LINK

End-Note:

1. The

South American sub-region includes: Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile,

Colombia, Ecuador, Guyana, Paraguay, Peru, Uruguay, and the República Bolivariana

de Venezuela.

2. Based

on official national accounts data.

3.The

developing Central and North America sub-region includes: Costa Rica, Guatemala,

Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, and El Salvador.

4. The

Caribbean sub-region includes: Antigua and Barbuda, The Bahamas, Barbados,

Belize, Dominica, Dominican Republic, Haiti, Jamaica, St. Lucia, St. Vincent

and the Grenadines, and Trinidad and Tobago.

5. Higher

mining output was led by increased production of alumina, boosted by higher

global demand.

6. The

central bank of Mexico raised its benchmark interest rate by 25 bps to 3.25

percent at its December 17th, 2015 meeting.

7. As

estimated in IMF 2015i.

8. Based

on official data.