As economies in developing Asia are quite diverse in population, demographics, and per capita GDP, it is no surprise that they vary widely in the size, structure, and complexity of their banking systems. They all have a common need, however, for supervision and regulation to keep their banking systems safe and sound. This means ensuring that their inevitable problems are manageable and that their bank failures, when unavoidable, are not large or systemic. Meanwhile, banks must remain able to meet credit needs.

By Asian Development Bank

As economies in developing Asia are quite

diverse in population, demographics, and per capita GDP, it is no surprise that

they vary widely in the size, structure, and complexity of their banking

systems. They all have a common need, however, for supervision and regulation

to keep their banking systems safe and sound. This means ensuring that their

inevitable problems are manageable and that their bank failures, when

unavoidable, are not large or systemic. Meanwhile, banks must remain able to

meet credit needs.

Image Attribute : Shanghai Skyline, China / Source: Wikimedia Commons

Given the huge

role of banks in Asia and the crippling effect of banking crises on growth,

regulatory authorities’ first line of defense against financial stability is

naturally the sound prudential supervision and regulation of these institutions

(Table 2.4.1). In addition, regulatory authorities in the region need to follow

guidelines set by Basel III core principles for bank regulation, which

were recently introduced to strengthen global regulatory standards in the

aftermath of the global financial crisis.

Southeast Asia

in particular has unique regulatory and supervisory challenges arising from

ongoing regional financial integration. The past 20 years have seen the

emergence and expansion of many large banking conglomerates throughout the

region. Some of these conglomerates operate banks that are systemically

important in more than one economy. Conglomerate interconnectedness poses

potential contagion risk—the possibility that problems arising in one affiliate

can spread to other affiliates through various mechanisms such as inter-company

transactions.

Bank

supervisory authorities in jurisdictions where conglomerates operate subsidiary

banks need to ensure timely and effective two-way communication and

information-sharing with their foreign counterparts. Coordination among

supervisors enables better understanding of the risks and financial soundness

of the conglomerate parent and its bank and other subsidiaries, as well as the

risks posed by transactions between affiliated organizations.

Basel III in Developing Asia

Those who set

international standards, such as the Financial Stability Board and the Basel

Committee on Banking Supervision, pursue reform agendas intended to reduce the

risks of bank failure and to mitigate the cost of failures and thereby preserve

public confidence in the banking system when they occur. In particular, Asian

banks are now confronted with Basel III and the tightening of the Basel

Committee’s core principles for bank supervision agreed in 2011–2012 in

response to the global financial crisis. That crisis resulted partly from a

serious failure of bank regulation in the advanced economies. Basel III

presents voluntary regulatory standards on bank capital adequacy, stress

testing, and market liquidity due to be implemented by March 2019. The initial

Basel principles were agreed in 1988 and revised in 2004 (Basel II).

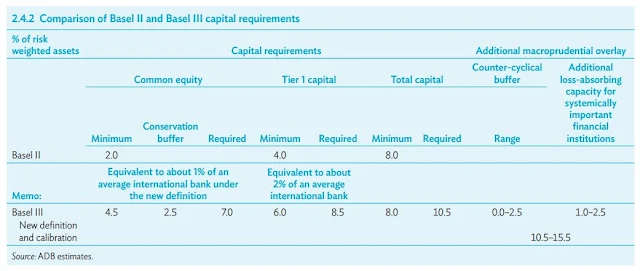

Table 2.4.2 compares Basel II and Basel III, and Table 2.4.3 outlines the

implementation table for Basel III.

Adherence to

the more stringent Basel III standards will further strengthen Asian banks’

balance sheets and mitigate their vulnerability to shocks. The regulatory

framework reduces opportunities for regulatory arbitrage and harmonizes

regulatory standards. However, the region must ensure that tightened

regulations do not seriously compromise banks’ capacity to fulfill their core

function of channeling credit to households and firms for investment and

production.

Banks in Asia

appear sound today even under the new stricter standards of Basel III thanks to

earlier efforts to strengthen their capital base, reduce nonperforming loans,

and bolster loan loss provisions, especially after the Asian financial crisis

of 1997–1998. However, another reason is that the region’s financial markets

are underdeveloped and not as exposed to sophisticated instruments as their

counterparts in more financially advanced economies. Bank capital, for

instance, is mostly held as simple paid-in capital and retained earnings.

Although they

preserve financial stability and improve transparency among banks, the new,

stringent regulatory standards raise the cost of financial intermediation and

limit the availability of bank credit. In upper-middle-income countries,

relatively scant and expensive bank finance will encourage the development of

bond markets, as their economies already have a core bond market and a growing

institutional investor base such as insurance companies. The tight leverage

ratio under Basel III will likely limit the supply of bank finance, as banks in

these countries often stretch their balance sheets. Moreover, capital

requirements will likely constrain the provision of bank finance for SMEs

unless efforts are made to enhance secured and unsecured lending and promote

nonbank finance for SMEs.

For

lower-middle-income countries, the challenges that Basel III pose are

somewhat different and more challenging. The new financial standards,

particularly liquidity requirements, are likely to constrain the generation of

medium- to long-term bank finance because financial systems are heavily dominated

by banks. While solvency policies are designed to encourage very long-term

investment by insurance companies, insurance industries are often too small in

these economies to compensate for the loss of medium- to long-term finance from

banks. Therefore, in addition to developing a base of long-term institutional

investors such as insurance companies and pension funds, regulators must, in

the meantime, induce banks to meet their capital adequacy requirements by

expanding their capital, not cutting back their lending.

Lessons from

the global financial crisis

According to

Zamorski and Lee (forthcoming), international experience during the global

financial crisis provides some valuable lessons for Asian bank regulators.

Above all, the crisis underlined that sound and effective bank regulation is

vital to financial stability. The crisis reflected the failure of regulatory

authorities to keep pace with financial innovation. The sobering lesson for

Asia and the rest of the developing world is that even financially advanced

economies are susceptible to risks from lax regulation and reckless lending.

Assessments of

the global financial crisis of 2008–2009 invariably point to ineffective

finance regulation and supervision as the main reasons for the onset of the

crisis and its severity. In particular, lapses in banking regulation

contributed significantly to the outbreak. Regulators allowed banks to operate

with excessive leverage and failed to curtail risky lending, primarily

mortgages to subprime homebuyers who were inadequately screened for

creditworthiness.

Bank

supervision had been weak by any measure. Supervisors did not conduct regular

onsite bank inspections or examinations of sufficient depth. They did not

properly implement risk-based supervision, and they failed to identify

shortcomings in banks’ risk-management methods, governance structures, and risk

cultures.

Instead,

overemphasis on banks’ historic operating results and static financial

conditions in assessing risk failed to reveal potential vulnerabilities.

Meanwhile, offsite surveillance systems relied too heavily on banks’

self-reported data to effectively monitor risk. Regulators failed to understand

the risk and policy implications of new bank products and services and changing

business models, or to establish effective lines of communication with their

counterparts in other economies, through which they could have shared vital

information.

Post-crisis

analysis by the International Monetary Fund, Financial Stability Board, and

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision identify additional aspects of bank

supervision that could have helped avoid the global financial crisis:

(i) Adequately

monitoring and controlling macro-prudential risk, and not just individual bank

risk, as a buildup of such vulnerabilities could hit a number of institutions

simultaneously, posing systemic risk;

(ii) Conducting

comprehensive stress testing of the banking system and other economic sectors,

taking into account highly risky scenarios even if they seemed unlikely;

(iii) Paying

attention to concentrations of risk and to interdependencies, including cross-border

risks; and

(iv) Considering

risks in the shadow banking industry or cross-sector risks posed by non-bank

financial intermediaries.

The last major

episode of cross-border financial instability and banking crisis in developing

Asia occurred more than 17 years ago. To extend this impressive record of

relative calm, bank supervisory authorities in the region need to assess their

supervisory systems, infrastructure, and actual practices. The lessons learned

in the global financial crisis will be useful to this process. If the

assessment reveals that changes, enhancements, or remedial action are needed, a

definitive plan should be crafted and implemented in a timely way.

________________________

Publication Details:

This article is a

part of a chapter for Asian

Development Outlook 2015

Creative Commons

Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO)

© 2015 Asian

Development Bank

6 ADB Avenue,

Mandaluyong City, 1550 Metro Manila, Philippines

Tel +63 2 632

4444; Fax +63 2 636 2444

www.adb.org;

openaccess.adb.org

ISBN

978-92-9254-895-7 (Print), 978-92-9254-896-4 (PDF)

ISSN 0117-0481

Publication Stock

No. FLS157088-3