They argued that people participated in the demonstrations because “a line had been crossed”: PX, believed to be highly toxic, was seen as “threatening people’s lives, regardless of class.”

By Dr. Ying Miao

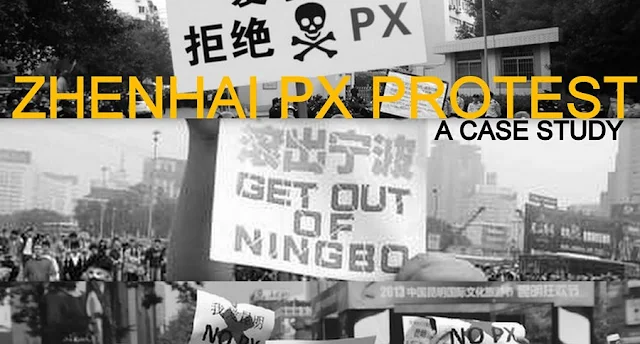

From 24 October through 28 October 2012, a series of protests erupted in Ningbo over the proposed expansion of a petrochemical plant to produce the industrial chemical paraxylene (PX) in the district of Zhenhai, a mere 15.5 kilometres away from the city center. Paraxylene is believed to have severe adverse effects on health, and associated projects have been highly controversial nationwide.Other PX-related projects have been rejected in the cities of Dalian and Xiamen, due to similar protests over health and environmental risks. Emotional pleas and propaganda filled the Internet for weeks leading up to the protest, peaking on the weekend of 27/28 October. The following day, on 29 October, the Ningbo Municipal Government conceded and announced that the project would be halted indefinitely, pending further review.

Although the media (especially the foreign media) were eager to portray the incident as a “middle-class uprising” [1]; [2], China Daily stated that the protests were not inherently a rebellion against the government or even the project, but that the main grievance arose from a lack of information about the project and government accountability for it [3]. Nevertheless, engaging in such an event of mass mobilization, as well as being in direct conflict with the authorities, is inherently political, thus this article’s enquiry into the nature of and participation in the PX incident is very telling of how respondents approached real-life socio-political events.

A series of multiple-choice questions were given to the respondents, who were asked to pick one or more statements that best matched their attitude towards and participation in the PX incident. Overall awareness of the incident was quite high: 65 per cent of all surveyed participants were interested in it. However, actual participation was very low: only 25 per cent participated online and a mere 6 per cent turned up at a protest or participated in some way offline. This is consistent with previous survey findings that suggest that the middle class have high civic awareness, but low civic association [4]. No significant correlation was found between respondents’ age, subjective class identity, and their participation. CCP membership and state employment status had a predictable effect on respondents’ participation: those who had closer ties with the state apparatus were less likely to participate in such politically sensitive events. When examined against their answers to the previous question set on abstract political concepts, it appears that respondents’ proclaimed political attitudes did have a degree of influence on their political behavior, though not tremendously: a larger proportion of those who believed civil society to be disruptive felt disinterested in the PX incident as a whole, while those who saw the government as being like the “head of a family” were generally more disinclined to get involved, whether through discussion or online participation, by a margin of 15 per cent. More interestingly, those who believed that the government should lead reforms were more likely to participate online, but steered away from offline protest, while those who did not believe the government had to lead reforms engaged in more offline activities. This suggests that those who believed in state-led reform initiatives saw online participation both as a legitimate outlet for their concerns and as being within the purview of the state, as the Internet is censored and monitored. Offline participation, by contrast, was seen to be an extra-state activity, and was thus less condoned by those who believe that the state has an essential role to play in the political process. Of course, the numbers of people who turned up at the protests were nevertheless low. Due to the overwhelming support for multi-candidate elections, the high standard deviation presented for the statement “I participated online in the PX incident” is more of an outlier on account of the small sample size, rather than any strong correlation.

The results of the semi-structured interviews with the smaller sample of respondents are more revealing, particularly in terms of how the interviewees remembered and explained the PX incident using their own rationale. None of the interviewed respondents believed the incident was an exclusively middle-class affair or that the middle class had played a prominent role in the events. Typically, they argued that people participated in the demonstrations because “a line had been crossed”: PX, believed to be highly toxic, was seen as “threatening people’s lives, regardless of class.” Often, they described the struggle as being between those who had a vested interest in the expansion of the chemical plant and those who had a vested interest in the safety and health of the local area. Some even thought that the middle class would be the least relevant party, since they would be able to move out of the area, leaving behind the poor as the most vulnerable to a polluted environment. One respondent argued that, if it were not for the fact that public health was at stake, people would never have taken to the streets to demonstrate against the plant.

The imbalance between the potential repercussions from and rewards for participation was a major factor in interviewees’ decisions to opt out of the protests. CCP members and the employees of state-owned enterprises and government institutions recalled how warnings against participating in the demonstrations were distributed to them through mass texts and departmental bulletins. Others stressed that they had a “normal life” at home, which they did not want to put at risk. Although they demonstrated a reasonably good understanding of popular political topics, these respondents preferred to keep their activities in the private sphere. Some respondents said that although they understood that those who took to the streets felt “their lives being threatened,” they did not share this sentiment, so they themselves declined to participate.

During the interviews, it became clear that the interviewees had various different rationales to explain other peoples’ “active” behavior and their own “passive” stance. Several respondents further identified the root of the problem as a lack of information dissemination and transparency about the PX plant, but did not feel the protest had legitimate environmental grounds.They expressed compassion and understanding of the protesters’ cause, but were able to analyse the issue beyond the superficial call to rally. Some respondents believed that the protesters had been misled, not in terms of the outcome of the protest, but in terms of the reasons for participating in the protests. One respondent argued that media exposure had put an unfortunate spotlight on PX, while many other more polluting chemical projects were being left un-examined. Though the sentiments and motivation behind the PX demonstrations were generally endorsed by respondents, they made a distinction between “understanding” and “participating.” Many indicated that they personally would not have followed the protesters to the demonstrations, as they felt the risks of participation outweighed the benefits.

It was clear that these respondents could readily acknowledge and accept the popular rationale behind the protests, but they also prided themselves in “being able to see beyond it.” As PX is believed to have adverse health effects, they could see that the public’s reaction was to be expected; however, because they believed that the adverse health effects of PX had been greatly exaggerated, many respondents felt the cause for protest had been sensationalized and they, therefore, saw the project as less of a threat than did the active protest participants. Instead, because they saw the struggle between industrial and commercial interests over this project, they wanted to disassociate themselves from anyone who appeared “rash” or “hotheaded,” as they felt that these individuals were prone to manipulation. Even though these middle-class respondents understood that protesters felt that “a line had been crossed,” for them, that line was still at some safe distance. Therefore, the costs of participating in this highly politically charged protest would outweigh the benefits. Nevertheless, the fact that they could sympathize with the protesters suggests that if, one day, that invisible line were to be crossed, then they too might join others in open protest.

To learn more about the findings, Kindly download the "Paper" - LINK

About the Author:

Dr. Ying Miao is a lecturer in the Department of China Studies at Xi’an Jiaotong Liverpool University, China. Her research interests include Chinese social stratification and change, socio-political change and the development of contemporary China, and comparative development between China and the West

Cite this Article:

MIAO, Ying (2016), The Paradox of the Middle Class Attitudes in China: Democracy, Social Stability and Reform, in: Journal of Current Chinese Affairs, 45, 1, 174–177.

URN: http://nbn-resolving.org/urn/resolver.pl?urn:nbn:de:gbv:18-4-9509

Publication Details:

Published by GIGA German Institute of Global and Area Studies, Institute of Asian Studies and Hamburg University Press. The Journal of Current Chinese Affairs is an Open Access publication, published under Creative Commons - Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works

References:

[1] Larson, Cristina (2012), Protests in China Get a Boost From Social Media, in: Business Week, 29 October

[2] French, Howard W. (2006), In Chinese Boomtown, Middle Class Pushes Back, in: The New York Times, 28 October, online: (1 September 2015).

[3] Yang, Li (2010), Respect the Villager’s Right to Know, in: China Daily, 30 October, online: (1 September 2015).

[4] Wang, Xin (2008), Divergent Identities, Convergent Interests: The Rising Middle-Income Stratum in China and Its Civic Awareness, in: Journal of Contemporary China, 17, 54, 53–69.