This article discusses the geopolitical dimension of maritime security, which has been neglected by scholars despite the growing number of studies devoted to a variety of aspects related to maritime security. T

By Basil Germond

Department of

Politics, Philosophy and Religion, University of Lancaster

Image Attribute: thebureauinvestigates.com / Creative Commons

Geographical

‘permanence’ such as the length of a country’s coastline or the absence of

direct access to the high seas constrains sea power in general and

maritime security policies in particular, “for geography does not argue. It

simply is” This in no way means that politics and policies are

determined by geography but that geographical factors need to be taken into

account in the list of explanatory factors along with other material,

structural and ideational factors.

Maritime security

has to do with (illegal and disruptive) human activities in the maritime

milieu, that is to say a certain geographically delimited space. Thus, states

are differently impacted by maritime security threats depending on their actual

geographical location. For example, in the case of illegal immigration by sea,

Italy is more directly impacted than (for instance) the United Kingdom, because

of its very geographical location. Sicily and especially the island of

Lampedusa are located directly on the main (and one of the shortest)

immigration route from North Africa to the EU and have thus sustained a

constant flow of illegal migrants for the past decades. In other words, even if

Britain, France or Germany may be the ultimate destination goal of illegal

migrants crossing the Mediterranean on small boats, Italy, Spain (through the

Gibraltar Strait) and Malta are more easily, quickly (and relatively safely)

accessible by boat than the UK or even France, due to evident geographical

factors. As a result Italy has to spend more resources on counter-immigration

than many other EU states, which explains its recent request for the EU’s

assistance in dealing with counter immigration at sea in central Mediterranean,

leading to the launch of FRONTEX operation Triton in November 2014. This

example illustrates that simple geographical realities have constraining

impacts on states’ maritime security policies, notably when it comes to

regulating human activities at sea.

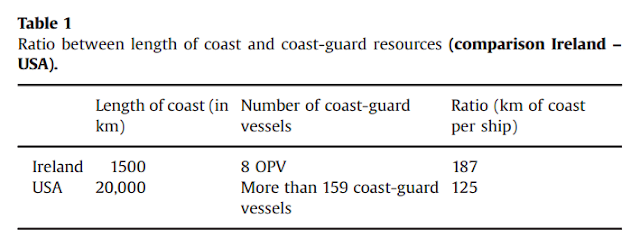

The same reasoning

works for other types of illegal flow within the maritime domain. For example,

drug smuggling directly impacts countries located on the main routes, such as

Spain through the Gibraltar Strait, or those whose coasts are difficult to

monitor due to a negative ratio between the length of the coast to police and

the resources at the disposal of the navy/coast-guard. This can be the case for

small states such as for example Ireland with limited resources and a rather

extended coastline or powerful states such as the United States, which despite

the resources at the disposal of its coast-guard service has such a long coast

to monitor and is the intended destination goal of so much drug trafficking

that it still struggles to ‘seal’ its maritime borders. Here the geographical

factor (length of coasts) is clearly not sufficient to explain the burden of

counter-narcotics. Material power (such as the coast-guard budget) and drug

traffickers’ business strategies (privileged destination countries) need to be

factored in the explanation. As shown in Table 1, the geographical factor is

still very relevant. Despite the US deploying almost 20 times more coast-guard

vessels, each of those vessels have a theoretical length of coast to monitor

that is just 62 km shorter than the one devoted to each Irish offshore patrol

vessels (OPV).

States’

involvement in maritime security also depends on nongeographical factors such

as governments’ capabilities and/or will to tackle maritime security threats.

For example, Somalia has not been in a position to control illegal activities

in its own territorial waters (hence the need for foreign maritime

capacity-building operations, such as EUCAP Nestor). Empowering secessionist

Somaliland’s and autonomist Puntland’s own coast-guard forces shows the

importance of political will and material realities as explanatory factors. It

has also been argued that in certain South East Asian countries, police or

naval forces are reluctant to engage in counterpiracy activities and could even

be “complicit in these crimes, especially in areas where a culture of

corruption (possibly boosted by underpaid maritime security forces or smuggling

activities) has evolved under years of authoritarian governments”

Due to the global

nature of the maritime domain and to the transnational nature of many of the

current maritime security threats (immigration, drug smuggling, piracy, etc.),

countries not directly impacted by the threats coming from the sea can

nevertheless decide to contribute to the policing efforts, based on the

understanding that they will eventually be impacted later. For example the EU

has set up the FRONTEX agency to deal with illegal immigration and coordinate

member states’ activities in this field, based on the principle that member

states are all impacted by the consequences of illegal immigration to the EU

whatever their geographical location. Counter-immigration at sea represents a

major part of FRONTEX’s budget and activities; in 2012, the largest share

(42.3%) of the agency’s operational budget (excluding risk analyses and research

& technology) went to sea borders joint operations (Frontex,: 32). In

2013, within the FRONTEX framework, North European countries such as Denmark,

Iceland, Finland, Latvia and landlocked countries such as Austria, Luxembourg

and even non-EU member Switzerland have contributed to counter-immigration

operations taking place in the wider Mediterranean area (Frontex, : 59).

This shows that states include geographically distant maritime regions into

their security perimeter, for transnational threats need to be tackled beyond

one’s external boundary. Controlling the sea far away from home is of strategic

value. It represents a means to expand one’s zone of control and competencies

beyond one’s external boundary, which can be considered as a form of

post-modern territorial expansion. It must however be noted that

overseas possessions imply the right and the duty to maintain a (naval)

presence there, which is mainly about affirming one’s sovereignty, although

overseas naval bases and prepositioning can also contribute to power projection

and naval diplomacy.

Maritime security

threats are also used in geopolitical discourses as an argument (amongst

others) justifying the projection of security beyond one’s external boundary. In other words, geographical representations framed within the

‘safe/inside’ versus ‘unsafe/outside’ dichotomy encompass maritime elements.

For example, the seas surrounding Europe are represented as vectors of threats

in both EU’s and member states’ discourses, which may then justify various

(sometimes controversial) projection activities in the maritime periphery of

Europe. Securing the freedom of the seas and policing the ‘global commons’

justifies projecting regulations, norms but also police and naval forces beyond

one’s territorial or jurisdictional waters. In other words, maritime security

has a geopolitical dimension. The control of distant maritime areas is

presented as vital to assure security on land. This construction of threats

along geographical lines and the practical consequences in terms of power and

forces projection are strengthened by the fact that the boundary between naval

deployments and maritime security operations is growingly blurred, which is

illustrated by counter-terrorist and counterpiracy operations currently taking

place at the Horn of Africa, which result in

the deployment of frigates within war-like coalitions. It is interesting to

note that the deployment of frigates instead of patrol vessels is mainly due to

geographical considerations; the units sent by the US, the Europeans or the

Chinese need to sustain operating for a long period far away from their bases,

which is beyond the capacity of many coast-guard patrol vessels. As will be

discussed below, the geopolitical dimension of maritime security also reflects

in current maritime security strategies.

This article is an excerpt from a research paper, titled - "The geopolitical dimension of maritime security" published by Elsevier at Marine Policy 54 (2015) 137–142

under Creative Commons License 4.0 | Open Access funded by

Economic and Social Research Council

Download The Paper - Link