The continuous expansion of global trade and shipping make these maritime choke points of the Indian Ocean ever more important as the volume of traffic through them increases. Some 30 per cent of world trade already passes through the Strait of Malacca each year, while some 20 per cent of worldwide oil exports have to pass through the Strait of Hormuz. The significance of the Indian Ocean will increase further because of rising demand for raw materials and the associated increase in shipping.

By Carlo Masala , Tim Tepel and Konstantinos Tsetsos

Bundeswehr University Munich

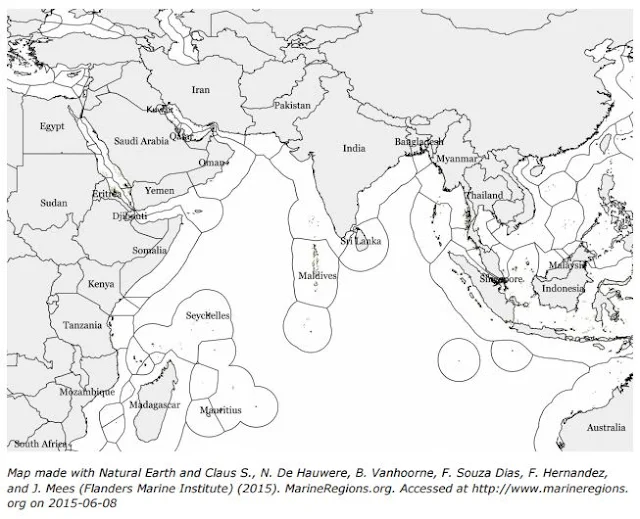

With an area of some 75.8 million km², the Indian Ocean is the world’s third largest ocean. It is linked to the Atlantic, the Pacific and the Antarctic Ocean and covers approximately 14.7 per cent of the surface of the earth. In the west, the Indian Ocean Region (IOR) extends from the Suez Canal in the north to the Cape of Good Hope in the South. In the north, two vast bays dominate the region (the Arabian Sea and the Bay of Bengal), while it borders the Antarctic in the south. In the east, the Indian Ocean borders the Southeast Asian coast and the western Indonesian Archipelago, and in the southeast the western Australian coast. While the Mediterranean was of preeminent significance in the Middle Ages and the Atlantic dominated in the modern era, the Indian Ocean is considered the most important ocean of the 21st century. Its importance derives from its narrow access routes and its role as the transit ocean for global trade. The region contains the most significant maritime choke points worldwide, namely the Gulf of Aden, the Bab-el-Mandeb, the Suez Canal, the Strait of Hormuz, the Strait of Malacca, the Sunda Strait and the Lombok Strait.

Image Attribute:

INDIAN OCEAN (July 16th, 2015) The

amphibious assault ship USS Bonhomme Richard (LHD 6) is underway during a

formation exercise between the Royal Australian Navy and the U.S. Navy. Ashland

is in the Indian Ocean participating in Talisman Sabre 2015, a bilateral

exercise intended to train Australian and U.S. forces in planning and

conducting combined task force operations. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass

Communications 3rd Class David A. Cox/Released) / 150716-N-KM939-181

The continuous

expansion of global trade and shipping make these maritime choke points of the

Indian Ocean ever more important as the volume of traffic through them

increases. Some 30 per cent of world trade already passes through the Strait of

Malacca each year, while some 20 per cent of worldwide oil exports have to pass

through the Strait of Hormuz. The significance of the Indian Ocean will

increase further because of rising demand for raw materials and the associated

increase in shipping. This will not only affect Western states but above all

also China and India, the most populous countries and among the leading

economies of the future. It will ultimately result in more and more countries

looking to secure their interests in the Indian Ocean, thereby boosting the

region’s geo-strategic relevance. Kaplan (2009: 17) believes that this will

produce major changes in international politics: “In other words, more than

just a geographic feature, the Indian Ocean is also an idea. It combines the

centrality of Islam with global energy politics and the rise of India and China

to reveal a multi-layered, multi-polar world.”

All the maritime

choke points mentioned above lie at security hot-spots in the Indian Ocean. Two

of the world’s most fragile states, Somalia and Yemen, are located in the west,

directly on the approach to the Suez Canal, the Gulf of Aden and Bab-el-Mandab.

The instability in these countries is having an impact on the maritime realm,

particularly as both Somalia and Yemen are currently facing civil war,

terrorism and transnational operating organised crime. The activities of Somali

pirates in the period from 2007 to 2012, which disrupted global sea trade, and

the attack on the USS Cole in the Gulf of Aden represent just two cases in

point. Further east, the competition between the USA and Saudi Arabia on the

one hand and Iran on the other has been endangering access to the Persian Gulf

through the Strait of Hormuz. Both the tanker war during the first Gulf War of

1980-1988 and the seizure of a Danish container ship operating under charter

from a German shipping company by the navy of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard

in April 2015 illustrate the tense situation as well as the vulnerability of

the sea routes in the Persian Gulf. Due to its location, its rivalry with

India, its nuclear arsenal and its ethnic composition, Pakistan is deemed to be

one of those fragile states whose collapse would have far-reaching and

threatening security implications. At the most easterly edge of the IOR lies

the Strait of Malacca; it is the most important sea link between Asia, Africa

and Europe, and it has also seen the majority of all pirate attacks since 2013.

Potential

for Interstate Conflicts

There are

numerous territorial conflicts and border disputes between various IOR

countries, which also impact on maritime security. Added to this are

international rivalries between external actors and states in the region.

Particularly in areas close to the straits, disputes about Exclusive Economic

Zones (EEZ) are resulting in interstate conflicts, which are impeding more

intensive cooperation. There are also conflicts of interests between IOR

countries with respect to accusations of illegal fishing in EEZs and the

resulting overfishing in the region.

Unrestricted sea

trade in the Persian Gulf is also coming under repeated threat from escalations

of other conflicts, such as those between the USA and Iran and between Saudi-Arabia

and Iran. Because of their inferiority in terms of conventional hardware, the

Iranian navies in particular (both the Iranian Navy and the navy of the

Revolutionary Guard) have specialized in asymmetrical naval warfare with very small boats, which represent a threat to both warships and civilian vessels.

The IOR is also increasingly developing into an arena of antagonism between the

USA, India and China with respect to spheres of geopolitical influence and

control over trans-shipment ports, sea links and natural resources. The region’s

significance for major powers and economies can also be gauged by the military

presences. The USA as well as Russia, the UK, France and China have ships

stationed in the region or regularly carry out exercises in collaboration with

bordering countries. There have also been signs over recent years of the

countries in the region investing more heavily in their navies in order to

enhance their power projection capabilities.

Piracy and

Maritime Terrorism

The IOR is the

global piracy hotspot. Between 2007 and 2012, activities by Somali pirates off

the Horn of Africa and in the Gulf of Aden seriously disrupted international

sea trade. In the east of the IOR as well, particularly in and close to the

maritime pinch point of the Strait of Malacca, over one hundred attacks on

ships of all sizes are recorded every year. And pirate attacks have also been

on the increase over recent years along the coast of Bangladesh. International,

regional and national security initiatives, such as the Combined Maritime Forces

(CMF) and the associated Combined Task Forces (CTF) with regional remits (CTF

150 operating in the Gulf of Aden, CTF 151 combating piracy and CTF 152

operating in the Persian Gulf), NATO operation Ocean Shield and EU operation

ATALANTA (to protect the ships of the World Food Programme), have resulted in a

serious reduction in piracy around the Horn of Africa, with only few attacks

taking place in 2014 and 2015.

However, the number of pirate attacks in the Strait of Malacca has increased

greatly in the same period, which makes the eastern IOR currently the most

dangerous piracy hot-spot in the world. Due to the fragility of numerous IOR

states, one also has to assume that the phenomenon of piracy will grow further

and may even extend into other sub-regions (such as Bangladesh). Even presently

secure regions may develop into piracy hot-spots again once the international

operations have come to an end. Scenarios of maritime terrorism cannot be

discounted either. As terrorist raids and attacks on ships are rare, albeit not

totally unheard-of, such activities happening in the Indian Ocean cannot be

dismissed out of hand. There are economically significant infrastructures in

the maritime environment as well as on land. A terrorist attack on an

international trans-shipment port in the IOR would result in incalculable damage

to an export-oriented economy such as Germany’s. The most notorious examples of

maritime terrorism include the following:

- In 1985, the cruise ship Achille Lauro was hijacked by terrorists from the Palestine Liberation Front.

- In 2000, the US destroyer USS Cole was badly damaged by a suicide attack in Aden harbour, which left 17 of the crew dead.

- In 2002, the oil tanker Limburg suffered a terrorist attack off Yemen. While the ship was waiting offshore to take on a further load of oil from the terminal, it was rammed on the starboard side by a dinghy that had been loaded with explosive. The explosion caused oil to spill into the Gulf and the incident disrupted international shipping in the area for several weeks.

- Critical infrastructures such as ports and oil production facilities are potential targets, as illustrated by the 2004 attacks on the Al Basrah and Khor al Amaya oil terminals.

Sea-based installations, such as offshore wind farms, can also become targets

for ship-borne attacks. Even if ships are not used directly as weapons, just

knowing that a sizable vessel is in the hands of actors intent on doing harm

can cause sustained damage to international trade. Important maritime choke

points (such as the Suez Canal) can become targets for terrorist attacks. A

ship being blown up, sunk or beached in a strategically chosen location could

potentially result in months of disruption to maritime shipping and energy

supplies.

Trade in Drugs, Weapons and People and Humanitarian Threat Scenarios

Due to the lack

of political stability, the IOR encompasses large drug growing areas. Opium

from Afghanistan in particular is supplied around the world across land and sea

routes. As the classic land routes to Europe are becoming less lucrative

because of stricter border controls, smugglers are using a new southern route.

The drugs are shipped from Pakistan across the Indian Ocean by sea to East

Africa, from where they are transported overland to North Africa and on to the

EU across the Mediterranean (particularly via Italy). In addition to the Afghan

drugs production, there is the “Golden Triangle” comprising Myanmar, Laos and

Thailand, where opium poppies are grown in large quantities and processed into

heroin before being shipped to neighboring countries by sea. Small arms are smuggled by similar routes. Criminal organisations with international networks

in particular but also terrorist groups use the drugs trade to fund their

activities. Human trafficking has been added to the picture, developing into a

further, highly lucrative business model rivaling the drugs trade (Potgeiter

2012: 11).

Ecological risks

in the region harbor further conflict potential, as the IOR states show poor

ecological sensitivity. Marine and coastal pollution is a wide-spread

phenomenon, endangering people’s health and safety. In addition, long stretches

of the coast are at risk of flooding, which could have far-reaching security

implications if large streams of migrants were to push inland (as happened

after cyclone Nargis in 2008) following a rise in sea level. The affected

states are inconsistent in prioritizing measures to improve environmental

protection and disaster control; their efforts are negligible compared to those

taken by other industrialized countries, and there is a need for further

international prevention initiatives.

Conclusion:

The Maritime

Great Game, which experts had expected to take place in the Indian Ocean, has

so far not materialized. Instead, the multilateral measures relating to the

fight against piracy and terrorism, to disaster control following the 2004

tsunami and to the demarcation of EEZ boundaries have shown that cooperative

courses of action are possible and that this is currently the approach

preferred by all the actors in the region. Due to the dependence on open sea

routes, the existing economic interdependence as well as common interests, the

Indian Ocean Region has therefore not yet developed into a stage on which

hegemonic antagonism is played out as people feared, but is moving tentatively

in the direction of cooper-ative negotiations. That said, the numerous arms

programs, and particularly the massive enhancement of naval capabilities,

illustrate the fragility of the current trend towards sustainable cooperation.

About the Authors:

Prof. Carlo

Masala is Professor for International Politics at the Bundeswehr University

Munich.

Tim Tepel is a

Research Associate at the Bundeswehr University Munich.

Dr. Konstantinos

Tsetsos is a Research Associate at the Bundeswehr University Munich.

Publication Details:

This work is an

abridged form of an article titled – “Maritime Security in Indian Ocean – For Greater

German Engagement in the ocean of the 21St Century”, published

by Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V. and licensed under Creative Commons license:

“Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Germany” (CC by-SA 3.0 de). Download the Paper - LINK