The first methamphetamine seizure in Afghanistan was recorded in 2008, a minor capture of four grams in Helmand province. Now, seven years later, some 17 kilograms of methamphetamine, popularly known as ‘crystal meth’, were seized in the first ten months of 2015, in 14 out of Afghanistan’s 34 provinces. The Ministry of Counter Narcotics warned about the growing number of methamphetamine users, while the Counter Narcotics Police of Afghanistan called for amendments to the current narcotics control legislation to address the low penalties for trafficking. AAN’s Jelena Bjelica visited the only forensics drugs laboratory in Afghanistan and sought to learn about this new drug phenomenon in the country.

The first

methamphetamine seizure in Afghanistan was recorded in 2008, a minor capture of

four grams in Helmand province. Now, seven years later, some 17 kilograms of

methamphetamine, popularly known as ‘crystal meth’, were seized in the first

ten months of 2015, in 14 out of Afghanistan’s 34 provinces. The Ministry of

Counter Narcotics warned about the growing number of methamphetamine users,

while the Counter Narcotics Police of Afghanistan called for amendments to the

current narcotics control legislation to address the low penalties for

trafficking. AAN’s Jelena Bjelica visited the only forensics drugs laboratory

in Afghanistan and sought to learn about this new drug phenomenon in the

country.

Afghanistan Analysts Network

Situated in a

northern neighbourhood of Kabul, state-of-the-art forensics drugs laboratory of

the Counter Narcotics Police of Afghanistan (CNPA) is an unlikely setting in a

war-torn country. Its six high-tech labs are equipped according to the latest

international standards, including a sophisticated instrument that can

determine the molecular structure of sampled drugs. (1) The head of the lab, Dr

Khalid Nabizada, proudly showed AAN the new German-funded building and

equipment and explained that, together with his five-man team, he used to work

out of a container-turned-lab in the well-guarded CNPA compound before they

moved into the new building in May 2014.

The lab also

features a prominent display cabinet of drug samples that have been examined by

Nabizada’s team. It showed drugs one would expect to find in Afghanistan:

opium, hashish, morphine and heroin. But there were also several samples of

methamphetamine and other synthetic drugs, like ecstasy and MDMA

(methylenedioxyphenethylamine). These synthetic drugs are central nervous

system, amphetamine-type stimulants (ATS), recreationally used for their

euphoria-like (‘rush’ and ‘high’) effects. (2) They have recently entered the

Afghan market and seem to be spreading around the country.

According to

Dr Nabizada, the number of methamphetamine samples analysed in the CNPA lab had

clearly increased, indicating an increasing prevalence of the drug. Where in

2011 the CNPA received only samples of 16 cases, in 2012 samples of 99 cases

tested positive for methamphetamine. In 2013, the number remained relatively

steady, with 93 cases, in 2014 this increased to 146 cases, to finally reach

206 cases in the first ten months of 2015.

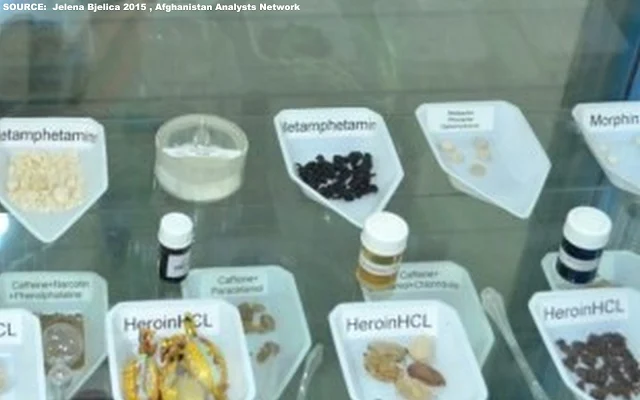

Image

Attribute: Samples of methamphetamine and other synthetic drugs, like ecstasy

and MDMA, exhibited in the display cabinet of state-of-the-art CNPA forensics

lab in Kabul, Afghanistan

(Photo by Jelena Bjelica 2015)

This also

tracks with an increase in methamphetamine seizures. Since the 2008 seizure of

four grams in Helmand, the amount of seized methamphetamine has significantly

increased. Drugs seized by CNPA mobile detection teams are sent to Nabizada’s

lab for weighing. In the glass-walled weighing room (which is according to the

highest international standards, as it allows the arrested person to witness

the procedure while sitting in the room next door), Nabizada and his team

carefully weigh each seizure, taking samples from each batch, before they store

it in the adjacent well-guarded drugs evidence room. The amounts weighed by

Nabizada’s team have been on the increase: from 2.6 kilograms in 2012, 4.9

kilograms in 2013, 4.1 kilograms in 2014, to a record high of 17 kilograms in

the first ten months of 2015.

According to

the Ministry of Counter Narcotics (MCN) 2012 Afghanistan Drug Report, the CNPA lab received methamphetamine

seizures from six provinces in 2012: Herat, Farah, Faryab, Kandahar, Balkh and

Kabul. The largest seizure was from Faryab province, 530 grams of methamphetamine;

the second-largest seizure, in Kandahar, was 240 grams.

In 2015, the

spread of seizures also increased: the 17 kilograms of crystal meth was seized

in 14 out of Afghanistan’s 34 provinces (Badghis, Baghlan, Balkh, Farah,

Faryab, Ghazni, Helmand, Herat, Kabul, Kandahar, Kapisa, Kunduz, Nimroz and

Parwan).

Local or

regional chemistry skills?

The seizures

show that in Afghanistan two types of methamphetamine are in use, crystal (in

Dari called shisha, which means “glass pane”) and tablets. The tablets were

mainly captured in Kabul and Kunduz and probably originate from Central Asia,

which is an emerging ATS market, according to the CNPA lab experts.

By far, most

of the meth, or shisha, is seized in the western Afghan provinces. Between

March 2009 and March 2013, according to the Afghanistan Drug Report, around 92

per cent of methamphetamine samples analysed by the CNPA forensics laboratory

were seized in western Afghanistan, namely in Herat, Farah and Nimroz province,

all close to the Iranian border.

It was

believed, until recently, that the crystal meth seized in Afghanistan

originated mainly from neighbouring Iran. Iran is indeed among the leading

producers of crystal meth in the region and the fourth-largest global importer

of pseudoephedrine, a precursor chemical used for methamphetamine synthesis. As

reported by the Guardian, 375 meth labs were dismantled and 3,500 kilograms of

meth seized by Iranian authorities in 2013 (see the Guardian story here).

Afghanistan, however, was also listed in the 2011 ATS Global Assessment as

among the countries with “unusually high requirements of ephedrine and

pseudoephedrine.”

Already in

2010 Pakistan’s authorities had reported the seizure of 12 kilograms of

amphetamine that they claimed originated from Afghanistan, but it was only in

September 2013 that CNPA’s mobile detection teams actually discovered and

dismantled a methamphetamine lab in Nimroz. (3) Additionally, the Global

Synthetic Drugs Assessment 2014

cautioned that since some ATS laboratories have been dismantled in

Central Asia “there are concerns regarding the spread of manufacture to

Afghanistan.”

The lead

character of the US crime television series Breaking Bad explained the secret

of making crystal meth as “basic chemistry.” According to a CNPA lab expert,

seven to eight recipes exist for cooking crystal meth. The easiest, and

cheapest, is done with ephedrine (or cough syrup), iodine and red phosphorous.

“If you have ephedrine, it costs almost nothing,” he said.

Interestingly,

according to Dr Nabizada of the CNPA lab, the meth seized in Afghanistan is “of

incredible purity; 90 per cent and over; absolute pure crystal.”

Lagging law

enforcement and sentencing

The 1971 UN

Convention on Psychotropic Substances was the first global attempt to prevent misuse

of central nervous system stimulants and to limit their use for medical and

scientific purposes.

Despite these

attempts to control it, crystal meth emerged as a new and commonly abused drug

on the bourgeoning rave scene in the USA, Europe and East Asia in the 1990s,

mainly due to its ability to elevate the mood and increase alertness,

concentration and energy. Many countries, as a result, sharpened their

penalties for crystal meth possession, supply and production, in some cases

awarding up to life imprisonment for the latter offence.

However, in

Afghanistan penalties for possessing and selling crystal meth are rather light.

The current Law against Intoxicating Drinks and Drugs and their Control (see

the law in Dari here and an unofficial UNODC English translation here) has

penalty provisions for amphetamine type stimulants that are the same as those

for cannabis. (4) Additionally, the threshold for considering the trafficking

of methamphetamine to be a major crime, and thus to be processed by the Criminal

Justice Task Force (CJTF), is the possession of 50 kilograms or more, the same

as for cannabis. To date, the CJTF has dealt only with one methamphetamine

case. The case concerned a person caught in Kabul in April 2013 with 3.5

kilograms of pure crystal meth, which, strictly speaking, was way below the

legal threshold. But it was also the single largest crystal meth seizure ever

in Afghanistan and, by international standards, an unusually high amount. The

person was sentenced to 15 to 20 years imprisonment, according to the Special

Bulletin of the Supreme Court.

The CNPA has

been leading an effort to amend the legislation to include much harsher

penalties for the trafficking of methamphetamine. The proposal includes a

penalty of up to 10 years in prison for the trafficking of more than 100 grams

of methamphetamine, and six to nine months, plus a fine, for the trafficking of

up to five grams. The Ministry of Counter Narcotics also warned, in its 2012

Afghanistan Drug Report, that the sentencing provisions for methamphetamine

trafficking were “inadequate to address the seriousness of the crime” and

suggested revising the law in line with international conventions and

sentencing guidelines so that it would be “in line with the threat posed by the

substance.” However, at this point it is unknown when the parliament will

discuss the proposed amendments to the law.

The drug for

rich kids

The number of

meth drug users appears to be on the rise, as MCN warns in its 2013 national

drug report (see also reporting by Reuters in 2013). Data, however, is very

patchy. The 2015 Afghanistan National Drug Use Survey estimated that there were

between 70,000 and 90,000 amphetamine-type stimulants users, which is a

relatively low number (well below 1 per cent of the population). (5)

“There is no

accurate data on use and prevalence of crystal meth in Afghanistan, but reports

from drug treatment centres and some other sources have recorded a large number

of the meth users in the western part of the Afghanistan, specifically in

Herat. However, the drug is easily available in most of Afghanistan,” Dr Raza

Stanikzai of United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) told AAN. He said

that although some treatment centres provide counselling treatment sessions to

meth users as a part of the regular drug treatment provided to opium or heroin drug

users, there are no treatments tailored to crystal meth available in the

country. (The most effective treatments for methamphetamine addiction are

behavioural therapies, such as cognitive-behavioural therapy, a former UNODC

drug demand reduction expert told AAN.)

To date,

street use of crystal meth has only been reported from Herat, Dr Stanikzai

says. In other urban centres, although available, crystal meth is not used in

public. The price of 20 US dollars for a dose, in contrast to 1.5 US dollars

for a dose of heroin, suggests that crystal meth use is mainly reserved for the

rich strata of the population and, therefore, unlikely to be widely used in

public.

An additional

problem is that, when asked, users usually say they have a problem with

“crystal” – using a Farsi slang word for the drug – rather than

“methamphetamine.” However, a type of high purity heroin is also called

“crystal” among drug users. “This adds a degree of confusion to the

registration, as treatment centres do not have the means to test for the

presence of methamphetamine and cannot be certain of the substance the patient

used,” noted the 2013 Afghanistan Drug Report.

Looking ahead

The growing

number of crystal meth seizures and the indications of an increase in use in

Afghanistan are worrying, given the country’s already heavy dependence on the

opium economy. Afghanistan continues to be the world’s leading opium producer

and cultivator (see AAN reporting on 2015 opium cultivation). With the already

high prevalence of opioid use – estimated between 1.3 and 1.6 million Afghans

(see 2015 National Drug Use Survey available here) – the country does not need

a new drug on the market. Crystal meth prevalence is still dwarfed by

Afghanistan’s opiate production and consumption, and it may never find its way

into all pores of the society in the way that the opium economy has.

Nevertheless, the production and trafficking of meth could add another

complicating layer to Afghanistan’s already complex narco-economy.

So far there

is no strong evidence to suggest that crystal meth is entirely indigenously

manufactured, but this may change. Heroin is currently locally produced,

whereas ten years ago it was not. If an increasing number of meth labs were to

be detected in Afghanistan, this would be an alarming signal. Afghanistan could

for instance follow the example of Myanmar, once a leading opium cultivator and

heroin producer, which replaced labour intensive opium cultivation with

synthetic drug production. Together with Thailand and China, Myanmar is now a

leading producer of synthetic drugs in South East Asia.

Such a

scenario for Afghanistan would involve a transformation of the nature of the

country’s drug economy, resulting in changes in local drug networks and

possibly even a ‘generation shift’ within it (in Myanmar, for instance, the new

generation of drug lords only embraced synthetic drug production after opium

cultivation was successfully phased out). But it is also quite possible that

meth trade and production simply will add to the already considerable list of

illicit sources of income. It is yet unclear who is likely to benefit.

(1) The

laboratory is equipped with the latest analytical instrumentation including Gas

Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry (GC–MS), High Performance Liquid Chromatography

(HPLC), Raman Spectroscopy, and Fourier Transform–Infra Red Spectrophotometry

(FT–IR) – and may be more sophisticated than many forensic drug labs in Europe.

Details about the lab can be found on the page 88 of the 2013 Afghanistan Drug

Report.

(2)

Amphetamine-type stimulants (ATS) are a group of substances comprised of

synthetic central nervous system stimulants, including amphetamine,

methamphetamine, methcathinone, and ecstasy-type substances (eg MDMA and its

analogues). Internationally, the production, distribution, sale and possession

of methamphetamine is restricted or banned in most countries.

Methamphetamines

and amphetamines were discovered in the late nineteenth century and are used

for the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), obesity

and narcolepsy. During the Second World War they were used by both the Allied

and Axis forces to keep pilots awake during night raids. In the 1950s,

amphetamine became known as a weight-loss drug and in the 1970s was widely used

as a recreational drug.

The latest

available UNODC estimate suggested that the retail value of the global illicit

methamphetamine market in 2008 was around 28 billion US dollars.

(3) “The

evidence from the dismantled labs suggests there were attempts to make crystal

meth in Afghanistan – in particular the traces of red phosphorous found in the

labs, which is usually used for cooking the meth. There is also anecdotal

evidence that Iranians trained Afghans in meth production, although this has

not been confirmed,” a CNPA lab expert told AAN, on the condition of anonymity.

(4) Article

47: Punishment for Trafficking of Substances or any Mixture Containing

Substances listed in the Tables of this law, prescribes the following sentences

for: More than 250 grams up to 500 grams, imprisonment for more than one month

up to three months; More than 500 grams up to 1 kilogram, imprisonment for more

than three months up to 1 year; More than 1 kilogram up to 5 kilograms,

imprisonment for more than one year up to three years; More than 5 kilograms,

in addition to three years imprisonment, for each additional 500 grams

imprisonment for three months.

(5) As

reported in the 2013 Afghanistan Drug Report, according to the Ministry of

Public Health records the highest number of methamphetamine users in 2012 in

Nimroz, Kunduz, Jawzjan and Farah provinces. The four provinces together made

for 96 percent of all registered methamphetamine users countrywide.

About The Author:

Jelena Bjelica

is an independent researcher and a former journalist. She is also a

practitioner in development, including with UNDP in Kosovo 2009 to 2010 and

with UNODC in Afghanistan 2010 to 2014. Her recent academic and other

publications include: Networks of Regressive Globalization and Challenges to

International Assistance Report: Case Study Afghanistan, Bojicic-Dzelilovic V.

and Kostovicova D. (eds), London School of Economics and Political Science

(2012); Human Trafficking and National Security in Serbia, in Migrations and

Media, Moore, K., Gross, B. Threadgold, T. (eds.), Peter Lang Publishing Group

(2012); Briefing Paper on 2009 Annual Programme for Kosovo (under UNSCR

1244/99) under the Instrument of Pre-Accession in the context of the 2009

‘enlargement package; European Parliament, Brussels (2010).

Cover Art Attribute: Pure shards of

methamphetamine hydrochloride, also known as crystal meth / Source: Wikimedia Commons

Publication Details