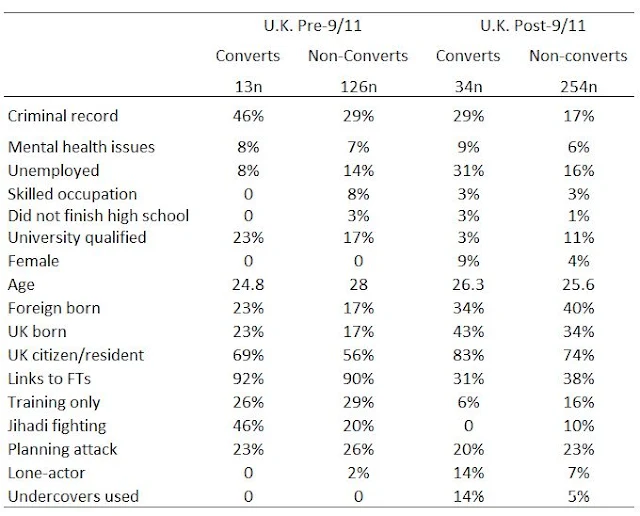

This article explores the role of converts in the ‘Global Salafi Jihad’ based on a sample of 75 American and 47 British converts who became involved in Islamist terrorism between 1980 and September 11th, 2013. Converts are compared to non-coverts on a variety of demographic, operational and investigative variables, and each sample is further divided into those who mobilized before and after 9/11 in order to allow assessment of changes over time. Contrary to previous research, results show that American converts in particular constitute a “jihadi underclass” that is markedly disadvantaged compared to the rest of the U.S. sample. They also present a generally less capable terrorism threat and are especially likely to be caught in sting operations. British converts, whilst also clearly disadvantaged and less capable, are much less distinct compared to non-converts in the U.K. Practical and theoretical implications of these findings are discussed.

- Was convicted of a relevant offence (whether under terrorism legislation or otherwise);

- Was killed during the course of terrorist activities, either at home and abroad;

- Was facing legal allegations at the time the analysis was conducted;

- Was subject to administrative or other sanctions in the absence of a conviction (detention, deportation, financial asset freezing and British control orders);

- Openly admitted their involvement in the GSJ, for example by way of appearing in a jihadi propaganda video;

- Was publicly alleged to have been involved in GSJ-related terrorism

but had not been subject to any legal action (including, for example,

numerous individuals from Minnesota who are believed to have joined

al-Shabaab).

- Wadih El-Hage. AQ operative. 1982–1998. Prosecuted.

- Ephron Gilmore. NY/NJ network, fought overseas. 1988–Unknown.

Public allegations.

- Daniel Patrick Boyd and Charles Boyd. Trained in

Afghanistan. 1989–1991. Confession/Public allegations.

- Christopher Paul. AQ links, planning attacks. 1990–2007.

Prosecuted.

- Abu Ubaidah Yahya. NY/NJ network. 1992–1993. Public

allegations.

- Kelvin E. Smith. NY/NJ network, provided training. 1993.

Prosecuted (non-terror).

- Earl Gant. NY/NJ network. 1993. Prosecuted (non-terror).

- Clement Rodney Hampton–El and Victor Alvarez. NYC

Landmarks plot. 1993–1993. Prosecuted.

- Aukai Collins. Fought in jihadi conflicts abroad. 1993–1996.

Confession.

- Jason Pippin. Trained in Kashmir, involved with Tarek Mehanna.

1996–2003. Confession.

- Abu Adam Jibreel al-Amriki. Killed in Kashmir. 1997–1998. KIA.

- Adam Gadahn. AQ spokesman. 1997–Ongoing. Confession.

- Jose Padilla. AQ operative. 1998–2002. Prosecuted.

- Earnest James Ujaama. Oregon training camp. 1999–2001. Prosecuted.

- Randall Todd Royer, Hammad Abdur–Raheem, Donald Thomas Surratt,

Yong Ki Kwon. Virginia jihad group. 2000–2003. Prosecuted.

- Hassan Abu Jihaad. Disclosed navy secrets. 2000–2001. Prosecuted

(non-terror).

- John Walker Lindh. American Taliban. 2000–2001. Prosecuted.

- Jeffrey Leon Battle, Patrice Lumumba Ford and October

Martinique Lewis. Portland jihad group. 2001–2002. Prosecuted/ Prosecuted

(non-terror).

- Clifton L. Cousins. Threatened George W. Bush. 2001–2003.

Prosecuted (non-terror).

- Rafiq Abdus Sabir. Offered support for AQ. 2001–2005. Prosecuted.

- Ryan Anderson. Tried to give military info to AQ. 2004. Prosecuted

(non-terror).

- Mark Robert Walker. Planned to join Somali jihadis. 2004.

Prosecuted.

- James Elshafay. NYC subway bomb sting. 2004. Prosecuted.

- Kevin James, Levar Washington and Gregory Patterson. LA

attack plot. 2004–2005. Prosecuted.

- Justin Singleton. Discussed jihad online, lied to FBI. 2005.

Prosecuted (non-terror).

- Paul Gene Rockwood Jr and Nadia Rockwood. Jihadi hit–list.

2006–2010. Prosecuted/Prosecuted (non-terror).

- Mohammed Reza Taheri–Azar. North Carolina vehicle attack March 3,

2006. Prosecuted (non-terror).

- Russell DeFreitas. JFK airport plot. 2006–2007. Prosecuted.

- Ruben Luis Leon Shumpert. Joined al-Shabaab. 2006–2008. KIA.

- Omar Shafik Hammami. Joined al-Shabaab. 2006–2013. Legal

allegations/Confession/KIA.

- Daniel Patrick Boyd. North Carolina jihadi plotters. 2006–2009.

Prosecuted (repeat offender).

- Carlos Eduardo Almonte. Conspiracy to join al-Shabaab. 2006–2010.

Prosecuted.

- Derrick Shareef. Mall attack sting. 2006. Prosecuted.

- Daniel Joseph Maldonado. Joined al-Shabaab. 2006–2007. Prosecuted.

- Bryant Neal Vinas. AQ operative. 2007–2008. Prosecuted.

- James Cromitie, David Williams, Onta Williams and Laguerre Payen.

NYC attack sting. 2008–2009. Prosecuted.

- Barry Walter Bujol Jr. Conspiracy to join terrorists overseas.

2008–2010.

- Troy Matthew Kastigar. Minnesota jihadi network. 2008–2009. KIA.

- Colleen Renee LaRose and Jamie Paulin–Ramirez. Conspiracy

to support terrorists overseas. 2008–2009.

- Michael C. Finton. Springfield, Illinois attack sting. 2009.

Prosecuted.

- Abdulhakim Mujahid Muhammad. Little Rock shooting, June 1, 2009.

Prosecuted (non-terror).

- Zachary Adam Chesser and Jesse Curtis Morton. Online

threats, attempt to join terrorists overseas. 2009–2010.

Prosecuted/Prosecuted (non-terror).

- Emerson Winfield Begolly. Promoting terrorism online. 2010.

Prosecuted.

- Antonio Benjamin Martinez. Baltimore attack sting. 2010.

Prosecuted.

- Randy Lamar Wilson. Planned to go to Mauritania for jihad.

2010–2012. Prosecuted.

- Marcus Dwayne Robertson and Jonathan Paul Jiminez. Jihadi

facilitation network. 2010–2011. Prosecuted/Legal allegations/Prosecuted

(non-terror).

- Walli Mujahidh and Abu Khalid Abdul-Latif. Seattle

military attack sting. 2011. Prosecuted.

- Naser Jason Abdo. Planned attack near Fort Hood. 2011. Prosecuted.

- Jose Pimentel. NYC attack sting. 2011. Legal allegations.

- Craig Benedict Baxam. Attempted to join al-Shabaab. 2011. Legal

allegations.

- Arifeen David Gojali, Ralph Kenneth Deleon and Miguel

Alejandro Santana Vidriales. Conspiracy to join AQ/Taliban. 2011–2012.

Legal allegations.

- Shelton Thomas Bell. Attempted to join jihadists in Yemen. 2012.

Legal allegations.

- Justin Kaliebe. Attempted to join jihadists in Yemen. 2013.

Prosecuted.

- Erwin Antonio Rios. Plan to commit armed robberies to fund jihad

(sting). 2012–2013. Prosecuted (non-terror).

- Matthew Aaron Llaneza. Oakland attack sting. 2012–2013. Legal

allegations.

- Nicole Lynn Mansfield. Killed fighting in Syria. 2012–2013. KIA.

- Eric Harroun. Fought in Syria. 2013. Prosecuted

(non-terror)/Confession.

- David Sinclair. Killed in Bosnia. 1993. KIA.

- Xavier Jaffo. Killed in Chechnya, April 12, 2000. 1995–2000. KIA.

- Andrew Rowe. International terrorist. 1995–2003. Prosecuted.

- David Courtailler. FPM network. 1997–2000. Overseas conviction

(France).

- Jerome Courtailler. FPM network. 1997–2001. Overseas conviction

(Netherlands).

- Abdullah el-Faisal. Jihadi ideologue. 1998–2002. Prosecuted.

- Abu Abdul Rahman Roland. Killed in Afghanistan. 1998–1999. KIA.

- Richard Reid. Shoe–bomb plot. 1998–2001. Overseas conviction (US).

- Dhiren Barot. US/UK attack plots (AQ). 2000–2004. Prosecuted

(non-terror).

- Martin John Mubanga. Alleged terrorist activity. 2000–2002. Gitmo

detainee.

- Feroz Abbasi. Alleged terrorist activity/FPM network. 2000–2001.

Gitmo detainee/Confession.

- Binyam Mohammed. Alleged terrorist activity. 2001–2002. Gitmo

detainee.

- Richard Dean Belmar. Alleged terrorist activity. 2001–2002. Gitmo

detainee.

- Jamal Malik al-Harith. Alleged terrorist activity. 2001. Gitmo

detainee.

- Abu Omar. Fought in Afghanistan. 2001–2002. Confession.

- Jamal Abdullah Kiyemba. Alleged terrorist activity. 2001–2002.

Gitmo detainee.

- Anthony Garcia. Fertilizer bomb plot (Operation Crevice).

2003–2004. Prosecuted.

- AP. Went to join jihadis in Somalia. 2004–2006. Control order.

- Atilla Ahmet, Kibley da–Costa and Mohammed al-Figari. UK

training camps. 2004–2006. Prosecuted.

- Jermaine Lindsay. 7/7 bombings. 2004–2005. KIA.

- Abu Izzadeen and Simon Keeler. Soliciting funds for

terrorism (AM). 2004. Prosecuted.

- Abdul Ishaq Raheem. Terror–supply network/Beheading plot.

2004–2007. Prosecuted.

- Umar Islam. Aircraft liquid bomb plot (Operation Overt). 2005–2005.

Prosecuted (non-terror).

- Yeshiemebet Girma. 21/7 post–event assistance. 2005. Prosecuted.

- Kevin Gardner. Army base attack plan. 2006–2007. Prosecuted.

- Nicholas Roddis. Bomb hoax. 2007. Prosecuted.

- Andrew Isa Ibrahim. Planned attack in Bristol. 2007–2008.

Prosecuted.

- Mohammad Abdulaziz Rashid Saeed–Alim. Attempted suicide bombing in

Exeter, May 22, 2008. Prosecuted.

- M1. Suspected terrorist activity. 2008–2009. Deported.

- Matthew Ronald Newton. Manchester terrorism recruitment. 2008–2009.

Prosecuted.

- J1. London Somali jihad cell. 2009–2010. Detention/Deportation.

- Abu Bakr and Mansoor Ahmed. Killed in Pakistan.

2009–2010. KIA.

- Richard Dart. (Attempted) overseas training/Planning domestic

attack. 2010–2012. Prosecuted.

- Minh Quang Pham. Joined al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP).

2010–2011. Legal allegations (US).

- Nicholas Roddis. Preparing for acts of terrorism. 2011–2012. Legal

allegations (repeat offender).

- Robert Baum and Christian David Erkart Heinze Emde.

Possession offences. 2011. Prosecuted.

- Samantha Lewthwaite and Jermaine Grant. Planning attacks

(al-Shabaab). Legal allegations (Kenya).

- Maryam. Joined jihad in Syria. 2013–Unknown. Confession.

- Michael Adebolajo and Michael Oluwatobi Adebowale. Murder

of Lee Rigby, May 22, 2013. Legal allegations (non-terror).

- Royal Barnes and Rebekah Dawson. Encouraging acts of terrorism online. 2013. Legal allegations.

![Table 1: Converts vs. non-converts involved in Islamist terrorism in the U.S. who mobilized before and after 9/11 (1980–September 11th 2013).[5] Table 1: Converts vs. non-converts involved in Islamist terrorism in the U.S. who mobilized before and after 9/11 (1980–September 11th 2013).[5]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgp4gYHGaavNsHxIfkj67Wzlczbm0AY5RtDhaEdMf92-iNa-5hn68JstT-PnBNLYCXcq5sR6yWHL03oJL05hOBg8Z8AZnbTxioSKVKJD_3npTpt0Ywr3yhswXZey-SK_NYKJzG_wnh0DQI/s640-rw/TABLE1.JPG)