It's about to be three years now, and the above statement by Dr. Rogers stands still like a permanent tombstone with respect to today's terror attack at Bamako's Radisson Blu Hotel.

By IndraStra Global Editorial Team

“The war in Mali and the recent attacks in Algeria are being seen as the start of a new phase of the war on terror across North and West Africa - an existential threat that could last decades. This is a dangerous simplification of a much more complex problem and risks becoming a self-fulfilling prophecy.” – Paul Rogers, Oxford Research Group, Jan 28, 2013

Image Attribute: Malian troops take position outside the Radisson Blu hotel in

Bamako

Habibou Kouyate/AFP

It's about to be three years now, and the above statement by Dr. Rogers stands still like a permanent tombstone with respect to today's terror attack at Bamako's Radisson Blu Hotel, The hotel itself is a popular place for foreigners to stay in Bamako, a city with a population approaching two million, and French and American citizens were among those taken hostage. Xinhua, China’s state-run news agency, reported that “numerous” Chinese tourists were staying at the hotel as well.

Kassim Traoré, a Malian journalist who was in a building about 50 meters,

or 160 feet, from the Radisson, said the attackers told hostages to recite a

declaration of Muslim faith as a way separating Muslims from non-Muslims. a similar approach was documented earlier during the attack at the Westgate Mall in Nairobi in 2013 by al-Shabab militants.

Epicenter of the Conflict:

In early 2012, Boko Haram fighters traveled, when the militant Salafist groups AQIM, MUJAO (Movement for Oneness and Jihad in West Africa), and Ansar al-Dine controlled the northern part of the country and established closer relations with these groups.

Epicenter of the Conflict:

In early 2012, Boko Haram fighters traveled, when the militant Salafist groups AQIM, MUJAO (Movement for Oneness and Jihad in West Africa), and Ansar al-Dine controlled the northern part of the country and established closer relations with these groups.

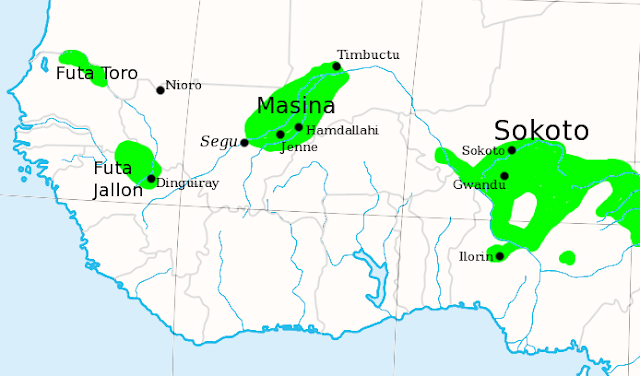

Image Attribute: Jihadist Objective is to create Fulani Empire / Sokoto Caliphate

Source: Wikimedia Commons

The Macina, a region that extends from the Mauritanian border to

the Burkinabe border, a particular vigilante militias Fulani have become

more radical and their rhetoric is not unlike that of Nigerian jihadists. Also, this region predominantly hosts a epicenter of the conflict around Mopti, as one of the main theaters of the violence eventually plaguing Mali. And those who inhabit it, for most of

the Fulani, are now a central concern of the Malian authorities and various foreign intelligence agencies.

"We are in a region marked by many community conflicts, said Boukary

Sangaré, an anthropologist who has been travelling to Macina since 7 years. For

most of the nomadic Fulani herders, have problems with the Tuareg or the Dogon.

When the rebels and jihadists arrived in 2012 and that the State machinery

system got disappeared, there was no one to settle disputes. So they had to arm

themselves to defend themselves. They sought help from the authorities, but

after their refusal, they turned to the jihadists in particular to Mujao. At the same time, Salafi ideas were gaining ground, sermons denouncing,

as in Nigeria against White's education in the form of Boko Haram.

After the French intervention and North area of the Macina was the first

region reoccupied by the Malian army. "The soldiers, who dreamed of revenge,

are all expressed their frustrations," said a French source. And the

Fulani have sometimes paid with their lives. NGOs are registered summary

executions and raids, but also insults and cattle rustling. "In some

cases, villagers even used as human shields for the soldiers, slips a UN

source. This has pushed people to take up arms and join the enemy jihadist

groups".

According to the same source, the whole event was seen at first as

"local initiatives for self-defense" has taken the guise of a

"structured movement" of which we know nothing

The French Perspective:

Image Attribute: A French Soldier talking with Malian Children / Source: Wikimedia Commons

The French assisted military advances and the re-taking of northern Malian towns had eventually lead on to a bitter guerrilla war, and reports of Malian Army atrocities against Tuareg communities played another major reason to further fuel the opposition.

From a French perspective, though, intervention was essential, given the

unexpected speed of the rebel advances in early January, which may have even

surprised the rebels themselves. Moreover, France had broad international

support, especially among western allies, as well as strong support from

Malians in Bamako and elsewhere in the more populated south of the country.

French military intervention developed rapidly, and by mid-February, there will

be 2,500 French military personnel in Mali, quite possibly backed up by a

similar number from ECOWAS states.

Even so, and whatever the strength of the arguments for intervention, it

must be recognised that this will be hugely welcomed by the wider jihadi

movement and its propagandists. What should under no circumstances be

underestimated is the impact of the air strikes, in particular. Coverage is

much greater in the Arab media than in the West and coverage by jihadist

propagandists through the new social media will be far more graphic.

Images of Mirage and Rafael strike aircraft and of the casualties and

damage will form part of a much wider narrative, joining a decade of

innumerable air strikes in Iraq and Afghanistan, drone attacks in Yemen,

Somalia, Afghanistan and Pakistan, and Israeli strikes in Lebanon, Gaza and

Sudan (widely seen as attacks by US aircraft in Israeli markings).

The Mali intervention may now be primarily French, but will be seen as

more broadly western, with UK and Canadian logistics aid, UK provision of

reconnaissance aircraft and reports of US offers of drone deployments

supporting this.

The Malian Perspective:

The Malian Perspective:

According to Dr. Rogers, long term sustainable stability for Mali will not be possible without

serious efforts to address the longstanding and deep grievances that stem from marginalization of the northern territories and its peoples, especially the

Tuareg. The French together with the Malian military and authorities will need

to address this issue, because there will be no unified Mali, if no solution is

found to accommodate the interests of the Tuaregs and other northern

populations. Socio-economic and political marginalization of the North has

deep-seated roots, and the ethnic/cultural dimensions (Tuaregs historically

enslaved black Africans) of this issue cannot be ignored. There is a

significant and well-documented history of rebellion and resistance by Malian

Tuaregs towards the colonizers (France) and later the central government.

The Malian government remained unwilling or unable to implement

development projects necessary to alleviate Tuareg poverty and marginalization,

failing to adhere to the terms and conditions of peace agreements reached under

the Tamanrasset Accords (1991) and National Pact (1992) and the Algiers Accords

(2006). A new talks process facilitated by the President of Burkina Faso,

Blaise Compaoré, on behalf of ECOWAS, began in Ouagadougou on 4 December 2012

engaging the Malian Government, Ansar Dine and MNLA. The talks, which had been

due to resume on 10 January, have been postponed. Further engagement is

essential.

It is the population’s resentment towards the central government over the marginalization of the northern territories, which has helped Islamists gain

support there. The chances of finding a solution to combating Islamic

extremism in northern Mali would have been significantly better had the Malian government looked at ways of collaborating with the Tuaregs. The only viable

long-term solution is cooperation and economic development for the region.

Conclusion:

Conclusion:

It’s a high time to frame all policies in terms of a willingness to

negotiate while recognizing the underlying problem of long-term marginalization. Islamists have latched on to deep and long-standing resentment and will best be undermined by fully recognizing this.

There is no pretence that this will be easy, especially as it is clear

that western political opinion has moved a long way towards a simplistic view

of this as part of an anti-jihadi war. The more it sees Mali in this light, the

more it will become just that, with dangerous long-term consequences. Indeed,

if western leaders speak in terms of an existential and generational conflict

across North and West Africa and act accordingly, that is precisely what they

will get.

AIDN: 001-11-2015-0452