By Dr. Mansee Bal Bhargava

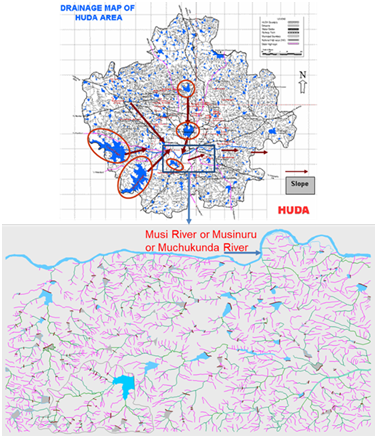

The ongoing flood in Hyderabad ([i]) and in most cities & towns of India during the monsoons this/every year are the result of, ‘Acts of Humans rather than Act of God’. These crucial maps developed for urban development, show the natural water system of a digital/smart Hyderabad comprising of a system of waterscape with Musi or Musinuru or Muchukunda River flowing west-east dissecting the city into north-south, a large number of lakes or ponds and innumerable unrecognized/unacknowledged small drains, mostly referred as ‘nala’ with a stigma of it being dirty. Similar maps are developed in several research outcomes for all the smart (and not so smart) cities of India where one can witness the existing system of waterscape([ii]). Ironically, the maps are left to be mere maps in the archive and sabotaged by the human endeavors collectively to tame the land and the water through urban planning and development resulting in fast deterioration and disappearance of the water resources ([iii]).

While more reasons for such floods are cited rightfully as, the encroachment of the land from the river&lakes banks ([iv]), and the wastewater discharge &solid waste dumping into the rivers&lakes ([v]); lesser is discussed about the state of the drains apart from they being dirty. If there is ONE thing as the root problem as well as the solution of the flood (and even drought and loss of biodiversity) in the cities/towns of India, it will be: addressing the systematic loss of the Drains and reclaiming them for relishing the rains and replenishing the rivers & lakes.

‘The Drains’were originally natural rainwater drainage courses interlinking the lakes and the rivers of a place. ‘The Drains’ traditionally in the form of streams, swamps, peats, wetlands, marshlands and were not as dirty as they happen to be now after getting engulfed in the urban development. The negative connotation as, ‘Ganda Nala/Naali’has occurred after they are turned into wastewater and solid waste dumping areas, for example, the Darbhavati River in Jaipur became Sukha Nala in a span of few decades. This forgotten as futile waterscape on the map, ‘the drains’, occupy nearly equal landmass alongside rivers & lakes in the cities. ‘The Drains’ need attention since they are the lifelines of the river/s & lake/s and the problem solvers of the flood-like situations of Hyderabad when the water is gushing on the streets in the absence of the network of water channels to bring water from one place to the other.

Source:CoreenaSaures, 2017 ([vi])

The article is written in two parts: first (this) as what citizens did with the drains (of Hyderabad and other cities); and second as what citizens can do with the drains instead. Why citizens? Simple! we citizens make the cities/countries. Blaming the government for every problem, in a country that fails to distinguish government and politics is naïve as those are made up of all kinds of citizens set in different institutional arrangements and empowered with various governing mechanisms. When we make the government officials, the politicians, the bureaucrats, the urban planners-designers, the civil engineers, the landscape architects, the architects, the builders, the businessmen, the hoteliers, the bankers, etc.; then we must own the decisions, actions, and consequences. Since citizens are at the core of the city governance, let us accept what we did and how government-governance is wrapped around it (Mansee Bal Bhargava, 2020).

There is a piece of drain shared by every citizen in a city! The state of the drains reflects the famous theory of, ‘The Tragedy of the Commons’ (Garret Hardin, 1968) where every citizen residing close to the drains (mis)appropriated it to the self-interest either by encroaching land of the drain or by dumping waste into it. Every small/large plot owner/developer has developed a tendency to extend upon (encroach) onto the public space (which is drain in this case) beyond the delineated (bought) area in the form of a line of trees, elevated plinth, planter, wall, step, ramp, gate, parking, overhang, and many more. There has been a gross violation of encroachment by those who can afford to reclaim land from the land of the drain for development, be it a bungalow, apartment, office, public building, hotel, school, college. Many have even gone to the extent of filling up the drains as deep as 20-40 feet. Architects/designers/planners, engineers, urban local bodies, science, and technology are party to such endeavors by offering legal-professional-technical services. At the same time, many poor people having problem to afford housing find the drains as a respite to inhabit. Further, citizens continue dumping waste into the drains and when they have become enough dirty, the option left is to either cover the drains to ensure water flow or fill the drains, neither of which is a good option. The short-term prevention of need (for some greed)of the citizens misses the long-term needs towards ecology & humanity for the future generation.

Source: S Sandeep Kumar ([vii])

The state of the drains also reflects the culture aligned with the famous theory of, ‘Prisoner’s Dilemma’ (Albert Tucker, 1950), where every citizen, while conveniently ignored and complacently encroached upon the drains intentionally, lawfully and technically in the disguise of urban development and now the smart cities; they are caged in a mindset that others/neighbors/politicians/governments are not doing things right and that their doing right may not solve the problem so why bother. Every citizen whether those dumping waste or encroaching part of the drain and/or those not doing anything about such acts are equal partners to the disappearing and distressed drains. The culture also extends to the famous theory of, ‘the Logic of Collective Action’ (Mancur Olson, 1965) as the citizens, who stand divided in various aspects, fail to come together in the absence of communication of a shared common dream, such as in this case it could have been green and clean development. And those coming together are not necessarily making the right choices, for example, the concretization of drains by either covering or canaling reduces their water and ecosystem capacity.

Then, there are citizens doing urban development and management either trained in planning, engineering, architecture, economics, management, and allied fields but are meagerly instituted and interested in water ecology to make the right decisions at the right place& time. Water education in the fields that heavily influence urban development is nominal and misses teaching-learning of hydrology, physiography, topography, limnology, biology, ichthyology, ornithology, and many more allied fields crucial to water sustainability and security. The multi-disciplinarity of water science need to transcend from preaching into practice with a passion for humanity and ecology. For example, heavy scientization of politics and politicization of science by politicians, elites, and professionals in the favor of capitalistic land-based real estate developments needs a serious accountability check through a strict legal framework. Water resources, since antiquity, are publicly-politically contested for the economy via land development and has cost most of India’s fresh sources of water within a century in the form of rivers & lakes and ironically unacknowledged drains. A better understanding of the science of integrated water resource management (Peter Mollinga, 2006) and interactive water governance (Mansee Bal Bhargava, 2019) isn’t enough if the operationalization is without a conscience. For example, the loss of water bodies and floods can be attributed to the lack of integrated land-water urban planning, as we continue practicing land-use urban planning with the value of a space ascribed to a land parcel’s designated use. Further, the urban designers and landscape architects, if/when involved in the urban development, instead of designing with nature (Ian Mcharg, 1969), paint a vague manicured kind of urbanscape for aesthetics with trimmed & tamed vegetation, water, biodiversity, and even land profile. For example, the very waterfronts of lakes & rivers to make the City Beautiful (AGK Menon, 1997) have gone way too far to merely please the people than parenting the planet.

Finally, the governmental aspects of the Drains can be pointed out to the definition, designation, delineated, and related property rights (Arun Agrawal and Elinor Ostrom, 2001). A relevant question is, why the urban developments could do away systematically with the drains and other water bodies (Mansee Bal, 2015)? The legal definition of the drain is weaker than the strength of the drain ecosystem, to either a stream or as wasteland depending on a number of criteria, leaving a lot of room for misinterpreting and misappropriating the drain from its loss of identity. The designation of the stream and/or wasteland as nala devalues the land and thus is further prone to misuse in disguise to provide greater value by reclamation of land. Important to point here is that any waterbody in a city without water is a piece of land for urban development and that land has been overvalued over water whereas, the land has no value but the use assigned to the land ascribes the value. This aspect has mostly worked against all kinds of water bodies. The delineation, formally and informally, of the area of the drains, has seen the maximum misappropriation. The channelizing/canalizing of the drains and the small extensions of public/private properties onto the drains in the form of road, parking, garden, building, backyard, etc. have led to the reduction of the water flow area of the drains. All these wrapped in the ambiguous property rights and ownership sums the apathy of the drains. While the urban local bodies do not own the property rights of drains, cities were planned with considering their non-existence. Further, the remote administration of the drains by the Revenue Department as patron of the water feature (according to the Constitution of India) augmented with remote maintenance by the urban local bodies hinted the citizens about the drains to be ‘the no man’s land’ available for land-water grabbing. Finally, as a policy, the Flood is looked at as a Disaster problem and Drought as a Water problem, whereas both are intricately interrelated and are likely to coexist spatially and temporally. This is where policy, planning, program, and projects need to do some vertical coordination in water governance.

These citizens led development aspirations have collectively resulted in the loss or choking of the drains as natural drainage courses to function as water carriers to let water smoothly flow between the lakes and with the river/s.In the absence of interconnecting drains and water bodies, Hyderabad that overbuilt itself is now experiencing streets turned into gushing water drains when the dammed water bodies have surpassed the full tank level of their capacity pushing the decision to open of the sluices of the dam to avoid some larger catastrophe from the dam.

Water distresses are humanly created out of a lack of integrated and interactive water resource planning, design, management, and governance that fail to signal to the society the rising distresses and to announce the need to shift towards responsible consumption and production of water goods and services. What is it required to be responsible? Individuals with their short term vested interests damage the Institutions that nurture them, citizens collectively do the same to the city that houses them. Least to start with is, accept that government neither dirty the drains nor encroaches upon it and that government is made up of we the citizens who do so.

Drains have the answer to both flood and drought but the alone government can’t do much about the reclamation or the loss of the drains unless citizens in all forms, mainly planners, developers, architects, decision-makers aka individuals holding positions in the Institutions, collectively (Ostrom, 1990) pledge to make the right decisions backed by science and conscience to avert the disasters and to ensure a water-secure future.

The focus in this article is on what citizens did with the drains. In the second part of the article, we shall discuss how the drains can be reclaimed for relishing the rains and replenishing the rivers & lakes to address the cities/country’s rising water distresses. A glimpse of the second part is shared as a tribute to the 10 Years of the National Green Tribunal (NGT[viii]) in India on the 18th of October. The NGTin one of its landmark decisions in the case of the ‘Drains’ of Delhi in 2014 ([ix]), had asked the Delhi Government to not just to clean up all stormwater drains but also ensure no sewage or solid waste ever enters them, in addition to warning for no drain to be covered. Covering of drains have the potential to cause environmental damage by changing the local biodiversity and hampering with the environmental functions like flooding & groundwater pollution; besides that leading to increased toxicity and health hazards owing to trapped gases. The report recommended, ‘Greening of the Drains’ ([x]). I’d wish that the NGT is more empowered to save and savor the country’s greens & blues, I leave that discussion to yet another possible article with a humble request to the NGT to come out louder and clearer on the importance of Drains to address the climate change and urbanization induced floods and droughts besides the fast-deteriorating urban ecology.

While we have managed to tame the mountains, forests, flora, and fauna, let us now accept that taming water further will be a challenge and a mistake given the rising climate change. Climate change and urbanization induced water distress are increasing than ever ([xi]) with the estimation that half the world population will be affected by 2025 (World Health Organization, 2018) and more by 2050 when the urban population will rise to 68% (United Nations, 2018). While India is riding the development paradigm of Smart Cities ([xii]) with a flimsy flag of Green Growth ([xiii]), it is among the most water distressed countries in the world (World Resource Institute, 2018) where climate change and urbanization impacts are integral to the economic growth. The concurrent urban floods and droughts with an implicit capitalistic approach to water services continue pushing the water conflicts of ownership, access, equity, sanitation, gender, and even transboundary. The Niti Aayog’s Composite Water Management Index (2019) already informs of millions in the country affected by the rising water distresses. To add to the apathy, while there is a plethora of policies & projects requiring coordination, there is an abundance of data on water requiring data management for better water management ([xiv]). The resilience planning with policies & projects are driven by more mitigation measures than prevention measures with often having a normative perspective of a ‘lost battle’. The rising water distress (Vishal Narain, 2000) in a country that is abundant in water resources ([xv]) and water wisdom (Anil Agarwal and Sunita Narain, 2001) is worth questioning and resolving.

References:

- Agarwal, A. &Narain, S., 2001. Dying Wisdom. Delhi: Centre for Science and Environment, CSE.

- Agrawal, A. and Ostrom, E., 2001. Collective action, property rights, and decentralization in resource use in India and Nepal. Politics & Society, 29(4), pp.485-514.

- Bhargava, M., 2019. Interactive Governance at Anasagar Lake Management in India: Analyzing Using Institutional Analysis Development Framework. In Kenji Otsuka edited, Interactive Approaches to Water Governance in Asia (pp. 197-225). Springer, Singapore.

- Bhargava, M., and Ast, J.A.V. 2020.WhyResourceGovernanceFails?: Examples from Urban Lakes in India

- Hardin, G., 1968. The Tragedy of the Commons. Science, 162, pp.1243-1248.

- Hardin, G., 1968. The Tragedy of the Commons. Science, 162, pp.1243-1248.

- McHarg. I. L., 1969. Design with Nature. Garden City, NY: Natural History Press.

- Menon, AG Krishna. 1997. Imagining the Indian City. Economic and Political Weekly, No 46; pp. 2932-2936

- Mollinga, P.P., 2006. IWRM in South Asia: A concept looking for a constituency. Integrated water resources management in South Asia. Global theory, emerging practice, and local needs, pp.21-37.

- Narain, V., 2000. India’s water crisis: the challenges of governance. Water Policy, 2(6), pp.433–444.

- Olson, M., 1965. The logic of collective action: public goods and the theory of groups. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Ostrom, E., 1990. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Tucker, A.W., 1950. A two-person dilemma. Prisoner's Dilemma.

Weblinks

[i]https://www.dnaindia.com/india/report-hyderabad-floods-tamil-nadu-govt-contributes-rs-10-crore-to-telangana-cmrf-2850922

[ii]http://www.rainwaterharvesting.org/downloads/hybad_dos.pdf

[iii]https://citizenmatters.in/ahmedabad-vanishing-water-bodies-21853

[iv]https://www.thehindu.com/news/cities/Hyderabad/eyes-wide-shut-to-rise-in-lake-encroachments/article32887879.ece) (https://www.thehindu.com/news/cities/Hyderabad/lake-encroachments-led-to-flooding/article32867026.ece

[v]https://citizenmatters.in/hyderabad-dying-lake-kudi-kunta-restoration-ghmc-citizens-11530

[vi]https://www.deccanchronicle.com/nation/current-affairs/070917/drainage-shortage-cripples-hyderabad.html

[vii]https://telanganatoday.com/plastic-chokes-nalas-drains-hyderabad

[viii]https://greentribunal.gov.in/about-us

[ix]https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/delhi/Dont-cover-storm-water-drain-National-Green-Tribunal/articleshow/32623479.cms

[x]https://www.thehindu.com/news/cities/Delhi/green-the-dirty-drains/article3945922.ece

[xi] https://science.thewire.in/environment/hyderabad-urban-flooding-climate-change-anomalous-rainfall-urban-infrastructure/

[xii]http://smartcities.gov.in/content/

[xiii]https://www.greengrowthknowledge.org/country/india

[xiv]https://niti.gov.in/sites/default/files/2019-08/CWMI-2.0-latest.pdf

DISCLAIMER: The views expressed in this insight piece are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of IndraStra Global.

![Source:CoreenaSaures, 2017 ([vi]) Source:CoreenaSaures, 2017 ([vi])](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEixcvGC2bVFnVuTKVWC_d_-zUS4-c9Ptyagocy5yemcOT_FUK4Px9Y5LQ2TQDuQU7zNDhf8oCt1tNWgh6rl7p-5zQY67GWolT4ufUJe1TV8Q1KzLWG9wYOMg0ff5lpCWqbVDv1neneUeSE/w640-h362-rw/image.png)

![Source: S Sandeep Kumar ([vii]) Source: S Sandeep Kumar ([vii])](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhXJlQSK2Cb0abnMV5_YW1NP3on4yuy3qENZEBr6mhfo__RdIUF7wmuZ292m_w7ow-SODjhBXkUBKZ-KN_HSLP1W-O1rYTrzuF8oarn0QjE0ugYzavk99Hs7MYMikmmHjLFdb0YZQzTP3E/w640-h430-rw/image.png)

COMMENTS