This is article is an excerpt taken from an original work of Dr. Sayuri Shirai which is published by ADB Institute as a Working Paper Series - No. 922 / February 2019.

Concepts of Central Bank Money

Central bank money refers to the liability of the balance sheets of central banks — namely, money created by a central bank to be used by fulfilling the four functions of money described earlier. Cash used to be the most important means of payment in the past. The amount of outstanding coins issued is much smaller than the amount of outstanding central bank notes in circulation due to the smaller units, so coins are used only for small purchases. Meanwhile, the development of the banking system and technological advances have given rise to interbank payments and settlement systems where commercial banks lend to each other. A central bank manages interbank payments and settlement systems through monitoring the movements of reserve deposit balances at the central bank. The amount of cash is issued based on the quantity demanded by the general public, which is associated with transaction demand (normally proxied with the nominal gross domestic product [GDP]) as well as the opportunity cost (normally a deposit rate paid by the commercial bank to the general public). Thus, a central bank supplies cash passively in response to changes in demand. A central bank provides commercial banks with cash by withdrawing the equivalent amount from their reserve deposit accounts; commercial banks then distribute the acquired cash to the general public on demand through windows of bank branches and/or ATMs.

Reserve deposits can be decomposed into required reserves (the amount set under the statutory reserve requirement system) and excess reserves (the amount in excess of required reserves). Banks use reserve deposits to lend to each other in the interbank market. In normal times, when the effective lower bound is binding, the central bank pays a (positive) interest rate on excess reserves (IOER), and this IOER forms a floor for the short-term market-determined interest rate corridors (while the ceiling is formed by a discount rate charged by the central bank when lending to commercial banks against collateral). The floor in the market interest rate can be established because no commercial banks should be willing to lend to each other at a rate below the IOER.

Both cash and reserve deposits are the safest and most liquid financial instruments held by commercial banks. Reserve money (base money or the monetary base [M0]) is comprised of cash and reserve deposits. Cash is regarded as legal tender by governments and central banks for all debts, public charges, taxes, and dues in their respective economies. The value of cash is stable in an economy where a central bank successfully conducts monetary policy in accordance with the price stability mandate (mostly at around 2% in advanced economies) and, thus, avoids substantially high

inflation or serious deflation. The value of reserve deposits is also stable and is equivalent to cash in a one-to-one relationship.

Differences in Features between Cash and Reserve Deposits

While both cash and reserve deposits constitute central bank money, they have different features (Table 1). For example, cash is physical money, while reserve deposits are digital currency. Digital currency is a type of currency available in digital form, in contrast with physical, visible cash. Moreover, cash is used mainly among the general public (thus called “retail central bank money”), is available 24 hours a day and 365 days a year and is usable anywhere within an economy where the legal tender status prevails. By contrast, reserve deposits are available only to designated financial institutions, such as commercial banks (thus called “wholesale central bank money”) and are used for managing the real-time interbank payments and settlements system. Wholesale central bank money is not necessarily available 24 hours a day or 365 days a year, depending on the computer network system managed by each central bank. With technology advances, central banks have been making efforts to improve systems for enabling faster and more efficient transactions.

From the perspective of users (the general public), the most important difference between cash and reserve deposits is that cash is anonymous and cash transactions are non-traceable since transactions cannot be monitored or tracked by the central bank that issued the cash. In contrast, all the transactions based on reserve deposits are traceable by the order of the time sequence of transactions made, since they are a digital representation of money that enables the recording of all footprints. Reserve deposits are non-anonymous since they are based on an account-based system that uses an owner register so that information—such as the ownership of money in the respective accounts and the number of money transfers from one account to the other—is available fully to a central bank. In addition, cash provides a peer-to-peer settlement form, while reserve deposits are non-peer-to-peer settlements as transactions between commercial banks are intermediated by a central bank. Because of anonymity and non-traceability, cash is often preferred by the general public who wish to maintain privacy but is often used for money laundering and illegal activities and tax evasion purposes. Cash handling costs are quite high when considering not only the direct fees (i.e., cost of paper and design fees to prevent counterfeiting) but also the security and personnel cost associated with the maintenance of cash provision and payment services by commercial banks, shops, firms, and individuals.

From the perspective of an issuer (a central bank), the most important difference between cash and reserve deposits is the presence or absence of an interest rate. Cash is an interest-rate free instrument, while a positive or negative interest rate can be applied to reserve deposits. It is known that a negative interest rate policy can be a monetary policy tool under the effective lower bound, as has been adopted, for example, by the European Central Bank (ECB), the Bank of Japan, and Sweden’s Riksbank. A negative interest rate policy can be applied by a central bank to the IOER and can be more effective if commercial banks pass the increased costs (arising from the negative interest rate) on to their retail bank deposits held by the general public to maintain interest margins and profits. This is likely to happen when the general public no longer utilizes cash (so mainly uses private sector money or bank deposits) and, thus, is unlikely to substitute cash with bank deposits in order to avoid a negative interest rate charged on bank deposits.

The performance of central bank money is examined by focusing on cash and reserve deposits separately. Cash is likely to rise as economic activities (proxied by nominal GDP) grow, reflecting transaction demand. Reserve deposits also tend to rise when greater economic activities are associated with the deepening of the banking system and, hence, an increase in bank deposits. Thus, this paper measures cash and reserve deposits by dividing these data by GDP in order to examine the trend excluding the direct impact coming from greater economic activities.

Figure 1 shows cash in circulation as a percentage of nominal GDP for the period 2000–2017 in advanced economies (the eurozone, Japan, Sweden, and the US). The ratio of cash to nominal GDP declined steadily in Sweden since 2008, suggesting that Sweden has progressed to become the most cashless society in the world. It is interesting to see that the Swedish cash-nominal GDP ratio continued to drop even after a negative interest rate policy was adopted on the repo rate (namely, the rate of interest at which commercial banks can borrow or deposit funds at the central bank for seven days) from February 2015 (–0.1% initially in February 2015, deepening to –0.25% in March 2015, then further to –0.35% in July 2015 and to –0.5% in February 2016 before increasing to –0.25% in January 2019 as part of normalization). This indicates that substitution from bank deposits to cash did not happen in Sweden despite a negative interest rate.

In contrast, the cash-nominal GDP ratios have risen over time in the eurozone, Japan, and the US. These rising trends were maintained before and after the massive unconventional monetary easing—namely, quantitative easing in the three economies and the negative interest rate policy in the eurozone and Japan. Japan’s cash-GDP ratio has been always higher than those of the eurozone and the United States, suggesting that cash is more frequently used in Japan as a means of exchange and store of value. This may reflect that Japan’s inflation has remained more or less stable at around 0% or in the moderately negative territory since the late 1990s. Japan’s preference for cash may also reflect its long-standing low-interest rate since the Bank of Japan implemented a series of monetary easing after the collapse of the stock and real estate bubbles in the early 1990s (see Shirai [2018a, 2018b] for details). It is also interesting to see that cash is growing fast in the US, even after the monetary policy normalization that has taken place since December 2015 with a continuous increase in the federal funds rate.

Regarding reserve deposits, Figure 2 exhibits the ratios of reserve deposits to GDP for the period 2000–2017 in the same four economies. These ratios in the four economies have risen after the global financial crisis of 2008–2009, perhaps reflecting the quantitative easing tool adopted in the presence of the effective lower bound (i.e., large-scale purchases of treasury securities and other financial assets). The US currently faces a decline in the ratio because the Federal Reserve has begun to reduce

its balance sheets by reducing the amount of reinvestment on redeemed bonds from October 2017—after having recorded a peak in October 2014 when the process of “tapering”, or a gradual decline in the number of financial asset purchases, was completed so that the amount outstanding of reserve deposits reached the maximum of around $2.8 trillion. The European Central Bank (ECB) initiated net purchases of financial assets from June 2014 and introduced a large-scale asset purchase program

in March 2015 but completed net purchases in December 2018 after conducting tapering. From 2019, a full reinvestment strategy will be maintained so that the size of the ECB’s balance sheet will remain the same. Sweden adopted quantitative easing in 2015–2017 and has since continued to engage in a full reinvestment strategy to maintain the number of holdings of government bonds. Currently, therefore, the Bank of Japan is the only central bank among advanced economies to continue asset purchases and, thus, expand reserve deposits and the balance sheet—although the pace of net purchases dropped substantially since a shift from the monetary base control to the yield curve control in September 2016.

In the case of emerging economies (India and the PRC), Figure 2 shows their cash GDP ratios for the period 2000–2017. The ratios in the two economies have not risen like in the eurozone, Japan, and the United States, even though the amount of cash in circulation has grown rapidly in line with GDP (reflecting transaction demand). In particular, a declining trend in the ratio in the case of the PRC is noticeable, and this is likely to reflect a shift in the money held by the general public from cash to bank deposits or other cashless payment tools in line with the deepening of the banking system and an increase in the number of depositors at commercial banks, as pointed out later. A sharp drop in the ratio in India in 2016, meanwhile, reflected a temporary decline in cash after the government suddenly implemented a currency reform. India’s government banned the ₹100 and ₹500 notes and instead introduced a new ₹500 note and issued new ₹2,000 notes for the first time. This currency reform was meant to fight corruption and anti-money laundering/illegal activities but created severe disruptions to economic activities by creating serious cash shortages. While the cash ratio recovered somewhat in the following year, it appears that the ratio was lower than the past trend, suggesting a moderate shift from cash to bank deposits or cashless payment tools. Meanwhile, reserve deposits in these two economies have remained stable (data are available only from 2007 in the case of the PRC); and this makes sense since the central banks have not conducted quantitative easing like those in advanced economies.

To summarize, central bank money grew rapidly during the period 2000–2017 in the selected advanced economies because of an increase in cash in circulation, with the exception of Sweden. In addition, central bank money expanded significantly as a result of the adoption of large-scale asset purchases as part of unconventional monetary easing tools in the face of the effective lower bound. Meanwhile, cash in emerging economies has grown rapidly but does not show a rising trend when cash is measured in terms of nominal GDP. India’s cash-GDP ratio remained stable until 2016, suggesting that India’s cash growth is associated with transaction demand. The 2016 currency reform created a sudden decline in the ratio. The ratio since then has recovered but appears to be lower than the previous trend. The declining trend is more visible in the case of the PRC, and this appears to reflect a shift in the payment tool used by the general public from cash to bank deposits or other cashless payment tools (such as Alipay or WeChat Pay), which has contributed to the banking sector

deepening as the prepaid system is linked to bank accounts. Reserve deposits in the emerging economies have remained stable due to a lack of an unconventional asset purchasing program. Overall, central banks in both advanced and emerging economies have continued to issue ample central bank money for various reasons.

This is article is an excerpt taken from an original work of Dr. Sayuri Shirai which is published by Asian Development Bank Institute as a "Working Paper" (Series - No. 922 / February 2019). / The original work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 IGO License.

About the Author:

Dr. Sayuri Shirai is currently a professor of Keio University (Japan) and also a visiting scholar at the Asian Development Bank Institute in Tokyo.

Cite this Article:

Shirai, S. 2019. Money and Central Bank Digital Currency. ADBI Working Paper 922, pp: 2-8. Tokyo: Asian Development Bank Institute. Available: https://www.adb.org/publications/money-andcentral-bank-digital-currency

References:

Shirai, Sayuri. 2018a. Mission Incomplete: Reflating Japan’s Economy, Second Edition, Tokyo: ADBI. https://www.adb.org/publications/mission-incomplete-reflatingjapan-economy.

Shirai, Sayuri. 2018b. “Bank of Japan’s Super-Easy Monetary Policy from 2013-2018”, ADB Institute Working Paper No. 896, Tokyo: ADBI. https://www.adb.org/publications/bank-japan-super-easy-monetary-policy-2013-2018.

Table 1: Main Features of Central Bank Money and Private Sector Money

From the perspective of an issuer (a central bank), the most important difference between cash and reserve deposits is the presence or absence of an interest rate. Cash is an interest-rate free instrument, while a positive or negative interest rate can be applied to reserve deposits. It is known that a negative interest rate policy can be a monetary policy tool under the effective lower bound, as has been adopted, for example, by the European Central Bank (ECB), the Bank of Japan, and Sweden’s Riksbank. A negative interest rate policy can be applied by a central bank to the IOER and can be more effective if commercial banks pass the increased costs (arising from the negative interest rate) on to their retail bank deposits held by the general public to maintain interest margins and profits. This is likely to happen when the general public no longer utilizes cash (so mainly uses private sector money or bank deposits) and, thus, is unlikely to substitute cash with bank deposits in order to avoid a negative interest rate charged on bank deposits.

Actual Performance of Central Bank Money in Advanced and Emerging Economies

The performance of central bank money is examined by focusing on cash and reserve deposits separately. Cash is likely to rise as economic activities (proxied by nominal GDP) grow, reflecting transaction demand. Reserve deposits also tend to rise when greater economic activities are associated with the deepening of the banking system and, hence, an increase in bank deposits. Thus, this paper measures cash and reserve deposits by dividing these data by GDP in order to examine the trend excluding the direct impact coming from greater economic activities.

Figure 1 shows cash in circulation as a percentage of nominal GDP for the period 2000–2017 in advanced economies (the eurozone, Japan, Sweden, and the US). The ratio of cash to nominal GDP declined steadily in Sweden since 2008, suggesting that Sweden has progressed to become the most cashless society in the world. It is interesting to see that the Swedish cash-nominal GDP ratio continued to drop even after a negative interest rate policy was adopted on the repo rate (namely, the rate of interest at which commercial banks can borrow or deposit funds at the central bank for seven days) from February 2015 (–0.1% initially in February 2015, deepening to –0.25% in March 2015, then further to –0.35% in July 2015 and to –0.5% in February 2016 before increasing to –0.25% in January 2019 as part of normalization). This indicates that substitution from bank deposits to cash did not happen in Sweden despite a negative interest rate.

Figure 1: Cash in Circulation in Advanced Economies (% of GDP)

Source: CEIC, US Federal Reserve of St. Louis, IMF.

In contrast, the cash-nominal GDP ratios have risen over time in the eurozone, Japan, and the US. These rising trends were maintained before and after the massive unconventional monetary easing—namely, quantitative easing in the three economies and the negative interest rate policy in the eurozone and Japan. Japan’s cash-GDP ratio has been always higher than those of the eurozone and the United States, suggesting that cash is more frequently used in Japan as a means of exchange and store of value. This may reflect that Japan’s inflation has remained more or less stable at around 0% or in the moderately negative territory since the late 1990s. Japan’s preference for cash may also reflect its long-standing low-interest rate since the Bank of Japan implemented a series of monetary easing after the collapse of the stock and real estate bubbles in the early 1990s (see Shirai [2018a, 2018b] for details). It is also interesting to see that cash is growing fast in the US, even after the monetary policy normalization that has taken place since December 2015 with a continuous increase in the federal funds rate.

Regarding reserve deposits, Figure 2 exhibits the ratios of reserve deposits to GDP for the period 2000–2017 in the same four economies. These ratios in the four economies have risen after the global financial crisis of 2008–2009, perhaps reflecting the quantitative easing tool adopted in the presence of the effective lower bound (i.e., large-scale purchases of treasury securities and other financial assets). The US currently faces a decline in the ratio because the Federal Reserve has begun to reduce

its balance sheets by reducing the amount of reinvestment on redeemed bonds from October 2017—after having recorded a peak in October 2014 when the process of “tapering”, or a gradual decline in the number of financial asset purchases, was completed so that the amount outstanding of reserve deposits reached the maximum of around $2.8 trillion. The European Central Bank (ECB) initiated net purchases of financial assets from June 2014 and introduced a large-scale asset purchase program

in March 2015 but completed net purchases in December 2018 after conducting tapering. From 2019, a full reinvestment strategy will be maintained so that the size of the ECB’s balance sheet will remain the same. Sweden adopted quantitative easing in 2015–2017 and has since continued to engage in a full reinvestment strategy to maintain the number of holdings of government bonds. Currently, therefore, the Bank of Japan is the only central bank among advanced economies to continue asset purchases and, thus, expand reserve deposits and the balance sheet—although the pace of net purchases dropped substantially since a shift from the monetary base control to the yield curve control in September 2016.

Figure 2: Reserve Deposits in Advanced Economies (% of GDP)

Source: CEIC, Bloomberg, US Federal Reserve of St. Louis, Riksbank, IMF.

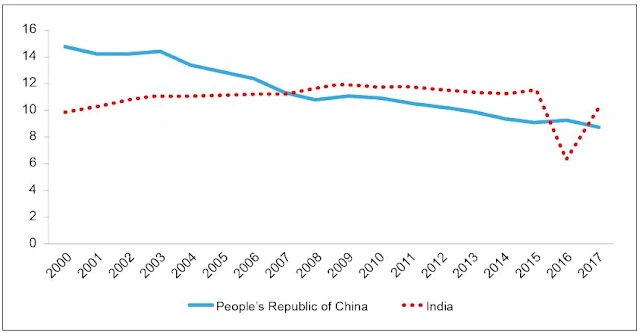

In the case of emerging economies (India and the PRC), Figure 2 shows their cash GDP ratios for the period 2000–2017. The ratios in the two economies have not risen like in the eurozone, Japan, and the United States, even though the amount of cash in circulation has grown rapidly in line with GDP (reflecting transaction demand). In particular, a declining trend in the ratio in the case of the PRC is noticeable, and this is likely to reflect a shift in the money held by the general public from cash to bank deposits or other cashless payment tools in line with the deepening of the banking system and an increase in the number of depositors at commercial banks, as pointed out later. A sharp drop in the ratio in India in 2016, meanwhile, reflected a temporary decline in cash after the government suddenly implemented a currency reform. India’s government banned the ₹100 and ₹500 notes and instead introduced a new ₹500 note and issued new ₹2,000 notes for the first time. This currency reform was meant to fight corruption and anti-money laundering/illegal activities but created severe disruptions to economic activities by creating serious cash shortages. While the cash ratio recovered somewhat in the following year, it appears that the ratio was lower than the past trend, suggesting a moderate shift from cash to bank deposits or cashless payment tools. Meanwhile, reserve deposits in these two economies have remained stable (data are available only from 2007 in the case of the PRC); and this makes sense since the central banks have not conducted quantitative easing like those in advanced economies.

Figure 3: Cash in Circulation in the People’s Republic of China and India (% of GDP)

Source: CEIC, PBOC, IMF.

Figure 4: Reserve Deposits in the People’s Republic of China and India (% of GDP)

Source: CEIC, PBOC, IMF.

To summarize, central bank money grew rapidly during the period 2000–2017 in the selected advanced economies because of an increase in cash in circulation, with the exception of Sweden. In addition, central bank money expanded significantly as a result of the adoption of large-scale asset purchases as part of unconventional monetary easing tools in the face of the effective lower bound. Meanwhile, cash in emerging economies has grown rapidly but does not show a rising trend when cash is measured in terms of nominal GDP. India’s cash-GDP ratio remained stable until 2016, suggesting that India’s cash growth is associated with transaction demand. The 2016 currency reform created a sudden decline in the ratio. The ratio since then has recovered but appears to be lower than the previous trend. The declining trend is more visible in the case of the PRC, and this appears to reflect a shift in the payment tool used by the general public from cash to bank deposits or other cashless payment tools (such as Alipay or WeChat Pay), which has contributed to the banking sector

deepening as the prepaid system is linked to bank accounts. Reserve deposits in the emerging economies have remained stable due to a lack of an unconventional asset purchasing program. Overall, central banks in both advanced and emerging economies have continued to issue ample central bank money for various reasons.

This is article is an excerpt taken from an original work of Dr. Sayuri Shirai which is published by Asian Development Bank Institute as a "Working Paper" (Series - No. 922 / February 2019). / The original work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 IGO License.

About the Author:

Dr. Sayuri Shirai is currently a professor of Keio University (Japan) and also a visiting scholar at the Asian Development Bank Institute in Tokyo.

Cite this Article:

Shirai, S. 2019. Money and Central Bank Digital Currency. ADBI Working Paper 922, pp: 2-8. Tokyo: Asian Development Bank Institute. Available: https://www.adb.org/publications/money-andcentral-bank-digital-currency

References:

Shirai, Sayuri. 2018a. Mission Incomplete: Reflating Japan’s Economy, Second Edition, Tokyo: ADBI. https://www.adb.org/publications/mission-incomplete-reflatingjapan-economy.

Shirai, Sayuri. 2018b. “Bank of Japan’s Super-Easy Monetary Policy from 2013-2018”, ADB Institute Working Paper No. 896, Tokyo: ADBI. https://www.adb.org/publications/bank-japan-super-easy-monetary-policy-2013-2018.