An excerpt, taken from Chapter 1 of ASIAN DEVELOPMENT OUTLOOK 2017 - Transcending the Middle-income Challenge

Image Source: Pixabay.com

Abundant global and local liquidity since 2008 has boosted commercial and household borrowing in developing Asia, more so than in other emerging regions. Macroeconomic vulnerability has worsened in some economies as a result, causing capital flow reversals and financial market volatility. The Fed’s tightening cycle has intensified fiscal and financial risk in the region, particularly in economies with highly leveraged private sectors. This requires close attention from policy makers.

Besides commercial debt (discussed at length in ADO 2016 Update), growing household debt has been a primary cause of rising leverage in the region. Fueled by the global availability of relatively cheap and abundant credit, consumer debt has surged in many Asian economies toward purchases of property, cars, and motorcycles, as well as many other consumer goods financed without collateral. Mortgage loans comprise the bulk of household debt in Asia.

Of some concern has been the speed with which household leverage has spiked in recent years. In the ROK, the ratio of household debt to GDP rose from 74% in late 2008 to nearly 91% in the third quarter of 2016. Thailand’s household debt ratio jumped by 26 percentage points in the same period, and Malaysia’s by 21 points, both reaching about 71%. In addition, the PRC, Singapore, and Hong Kong, China saw household debt increase substantially. In other economies where data are available, including India and Indonesia, debt ratios grew less and remain low (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Household debt

In Malaysia, sustained economic growth in recent years has boosted household incomes and consumer confidence, encouraging debt acquisition. Buoyant credit demand has come from a relatively young workforce and the influx of a more affluent population in urban areas, as home purchases continue to account for the largest portion of household debt. Government policies instituting fiscal incentives for home buyers, streamlined and reduced duties on cars, and a government-sponsored property lender have further spurred demand for household credit.

Thailand’s debt levels also reflect the impact of quasi-fiscal measures. Following floods in 2011, the government introduced a program for first car buyers in 2012 to support the hard-hit auto industry, raising demand for auto loans (IMF 2016). The program has since expired, but its impact on household debt lingers. Households have relied on credit cards to smooth consumption, further raising their debt. A survey conducted in September 2016 confirmed that recent increases in average household debt resulted mainly from purchases of vehicles and other consumer products, often using credit cards (University of the Thai Chamber of Commerce 2016).

Household leverage in some Asian economies has reached high levels were seen in mature economies, which sets the region apart from the rest of the developing world, where households are generally less indebted. By itself, household debt is unlikely to trigger financial crises in the region, at least not if unemployment stays low, asset prices remain fairly stable (Figure 2), and banks continue to be profitable and well capitalized (Figure 3). None of these parameters currently poses a problem for highly leveraged economies in the region. In Malaysia, for example, households’ capacity to service debt has been supported by stable domestic employment and a favorable income outlook. Heightened market volatility has caused a small decline in the value of household equity investments, but the aggregate household balance sheet remains healthy, with household financial assets valued at double their debt in the past 5 years. Further, stress tests suggest that potential bank losses are limited in Malaysia and easily covered by banks’ capital buyers.

Figure 2: Real property prices

Figure 3: Capital adequacy ratio

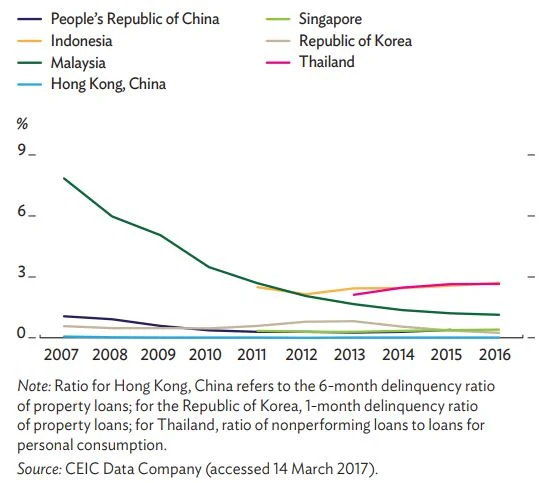

Ratios of nonperforming mortgage loans have remained low in the region. This is true even in Thailand, where delinquencies have increased in recent years, mostly involving younger people (Figure 1.3.5). The balance sheets of Thai commercial banks remain healthy, though other specialized financial institutions are more exposed to lower-income households. A recent Bank of Thailand assessment of these institutions found no imminent systemic risks but recommended heightened vigilance about sector risk exposure.

Figure 4: Mortgage nonperforming loan ratios

However, households, financial systems, and central banks are bound to feel it this year when rising US interest rates exert upward pressure on local borrowing costs, which have been fairly stable in the past 5 years (Figure 5). Higher rates will challenge households’ ability to service debt, particularly in economies such as Malaysia that have seen household debt service ratios rise (Figure 1.3.7). Loan delinquency will increase as a result, and households’ financial struggles may depress private consumption. In this situation, central banks could find themselves torn, wanting, on the one hand, to lower interest rates to support growth and householder balance sheets, but on the other to raise rates to stem capital outflow and support national currencies.

Figure 5: Short-term interest rates

Figure 6: Debt service ratios of households

This could be the case in the ROK, where low-interest rates and government stimulus that eased property regulations have lifted household leverage ratios to the highest in developing Asia. Although delinquency ratios remain low, at 0.5% for bank loans and 2.7% for non-bank loans, the pressure on households and the financial system is rising fast. The June 2016 Financial Stability Report from the Bank of Korea, the central bank, shows that nearly a third of household debt is held by households in distress, whose net financial assets are less than zero and who spend at least 40% of their disposable income on debt servicing. With 62% of mortgages at floating rates and another 30% with adjustable rates that shift to floating rates a certain point, the sector is highly vulnerable to a sharp hike in interest rates, particularly if combined with a growth slowdown and rising unemployment that would complicate central bank intervention.

To stem the risks of raising interest rates, the government has raised the target share of fixed-interest loans in bank portfolios; borrowers are encouraged to use them to refinance their adjustable-rate loans. In August 2016, it further tightened banks’ loan-screening requirements and lending by mutual finance institutions. This followed a more comprehensive package to manage household debt implemented the year before that sought to improve household loan quality, sharpen the assessment of borrowers’ repayment ability, and strengthen banks’ ability to respond to shocks and absorb losses.

Other policymakers in the region have been monitoring rising household debt for the past several years and enacting macroprudential policies to strengthen household and bank financial health. For example, Bank Negara Malaysia recently tightened limits on loan-to-deposit ratios and unsecured lending. It also required domestic banks to improve the asset quality of their balance sheets. The Bank of Thailand has been using loan-to-value ratios to limit household leveraging and property speculation.

In some other economies, though, macroprudential

policies remain relatively loose, and across the region the

sensitivity of household debt to changing interest rates remains a risk

to financial stability. This requires policy makers to stay vigilant and

tighten policy where warranted. In particular, the authorities should

assess the scope for further tightening loan-to-value and debt-toincome

ratios and requirements that banks set aside special reserves

and actively monitor and account for debt service ratios in their lending

decisions. Further interventions may be needed in some housing

markets to cool speculative demand and avoid asset bubbles.

Publication Details:

This article is an excerpt taken from Asian Development Outlook 2017, Chapter 1- Solid Growth Despite Policy Uncertainty, Pg 27-30, written by Valerie Mercer-Blackman, Arief Ramayandi, Benno Ferrarini, Madhavi Pundit, Shiela Camingue-Romance, Cindy Castillejos-Petalcorin, Marthe Hinojales, Nedelyn Magtibay-Ramos, Pilipinas Quising, and Dennis Sorino of the Economic Research and Regional Cooperation Department, ADB, Manila. Available under a CC BY 3.0 IGO license.