Modern propaganda and disinformation cannot be fought with coordination and funding alone, we desperately need new approaches that take into account the rapidly changing information environment.

By Alicia Wanless

Image Attribute: Uncle Sam, Source: Wikipedia

U.S. Senators Rob Portman and Chris Murphy recently introduced a new bill aimed at countering foreign propaganda. The legislation, presented at an Atlantic Council conference, is “aimed at improving the ability of the United States to counter foreign propaganda and disinformation, and help local communities in other countries protect themselves from manipulation from abroad.” The bill, if passed, would launch a “Center for Information Analysis and Response” that would oversee coordination of all U.S. counter-propaganda efforts.

With an emphasis on empowering people in countries affected by perceived disinformation, the “Countering Foreign Propaganda and Disinformation Act” is a step in the right direction in coping with a changing information environment. While the intent can be applauded, the devil is in the details. What follows is an assessment of some of the challenges that will be faced, as well as suggested directions for countering propaganda in the 21st century.

Propaganda and the New Media Matrix

The tools and methods of the Digital Age have drastically transformed the way we approach propaganda. Before the Internet, information was somewhat more easily controlled. Mass media was a one-sided affair, with messages carefully crafted and broadcast out to the audience, who passively consumed such content. Those with money or power had the ability to control the flow of information – whereas the general public had limited means for acquiring content – via TV, radio, newspapers, libraries, or whatever personal networks they had which were usually restricted by geography and sometimes censorship laws. This meant that not only was the information environment more easily manipulated by those who controlled it, it was also more difficult to feed disinformation into such restricted media networks, essentially making external propaganda less effective.

The Internet has greatly changed the information environment. People now have access to far more information than ever before, and from greater distances instantaneously. This means a person is no longer reliant on a major news outlet alone to receive information about a far-flung place – they can just as likely interact with people in that distant land online through social networks, forums or other Internet-based media. While the Internet has presented the opportunity to become better acquainted with the world, it has also facilitated the manipulation of information and perspectives at alarming rates.

Considering the average person now spends eight hours a day consuming media (more than 10 hours for those living in the Americas and Eastern Europe), often on multiple devices at once, people are essentially plugging into a media matrix whereby, on one hand, they can access more information than ever before and, on the other, are positioned to be more susceptible to manipulation. It is little wonder that governments are concerned – especially so given how actors such as Daesh have been able to use this media matrix effectively to their advantage.

Some of the avenues for audience manipulation enabled by the Internet include:

- The perpetual news cycle encouraging media outlets to break stories at lightening speeds increases the likelihood that disinformation will be published as news.

- Given how individuals are regularly distorting information online to present themselves in a better light on social networks (coupled with a prevailing preference for “infotainment”), the average person is also growing increasingly more likely to accept disinformation as fact – particularly if that disinformation conforms to one’s existing beliefs.

- The Internet can also help create the illusion of mass support through astroturfing techniques, whereby fake accounts are used to present popular support or dissent on issues, in turn, helping manipulate the cognitive bias of social proof, encouraging people to adopt the seemingly widely professed opinions of others similar to them.

- Every two days more new information is generated than was created cumulatively before 2003. Considering that we have not had any great leaps in evolution over the past 50,000 years, it is not likely that human minds are well equipped to cope with this onslaught of information. Indeed, to sort through this vast and growing amount of data, people rely on algorithms to return findings on search queries and sort news feeds based on preferences.However, this puts immense power in the hands of service providers such as Google or Facebook, who have the potential to influence voting decisions and create echo chambers reinforcing biases.

In this changed information environment, the old one-sided approach of broadcasting counter-messaging is no longer effective in persuading populations. And, while the Senators Portman and Murphy are correct in that the Voice of America and its sister organisations are ill-prepared for countering modern propaganda, it is not simply a question of funding, but very out-dated approaches.

Propaganda Begets Propaganda

The tenets of modern warfare place a significant emphasis on winning hearts and minds, or in other words ‘information operations’. In the highly globalized and inter-connected world with trade, financial and infrastructure linkages, the prospect of an all-out war between opponents is perceived as a ‘last resort’, simply because physical destruction (including tactical nuclear weapons) is likely to have an adverse effect on the attacker as well. In most military doctrines and national security policies worldwide, (be it the U.S. and its allies, or Russia and China), strategists focus on methods aimed at influencing people’s perspectives at home and abroad. The new paradigm is: he who manages to shape opinions successfully will be the new master. However, unlike in traditional, physical wars, ammunition (or content) lobbed at an opponent can just as easily be picked up and thrown back in return: that is to say, everything said, can and will be used against you. We are entering into an era of perpetual information war – old approaches such as criticizing opponents, fighting with facts and banning information simply do not work in this new environment.

Criticism Feeds Conspiracy Theories

Much of the difficulty is perception. As humans, the way we see the world leads us to believe that others must see it in the same way. This makes understanding the mindsets of those who support dictators more challenging. A common tactic for fighting an enemy combatant with information is to criticize that state’s leader, in the hope that increased criticism will erode support for the target: If only the people knew. The problem with this approach is that it assumes that criticism automatically leads to a growing doubt planted in the minds of those among that target audience. More often than not, however, such criticism can actually be turned into support, by using the increased exposure as PR, or even spinning it into conspiracy theories.

Some Russian news outlets, for example, have been using attacks on credibility as a way to gain increased media coverage. RT (formerly Russia Today) positions itself as an alternative voice in news. It is a strategically smart move. Every time someone, particularly from the West, criticises RT, the outlet can simply refer to its positioning as the motive for such challenge. In other words, Russian media claim that it is attacked because it alone offers a counter narrative to the English-dominated Western news hegemony. Not only does such criticism provide RT with controversy and thus free PR, especially when such attacks equate the outlet to Daesh, but it also lends legitimacy, at least among those who already accept the outlet as a true alternative source.

Political leaders who are attacked can adopt the same positioning. (Indeed, closer to home, presidential candidate Donald Trump has taken this tack, and with some success.) Criticism of opponents can be used, in turn, actually to bolster support, rallying followers around the target. While international criticism might help reinforce prevailing beliefs about a target among American audiences, it will (and does, in the case of Putin) only help increase support in the target’s country.

Russians overwhelmingly support Putin with an 86% approval rating. And a slightly higher percentage of Russians (88%) believe that the West is conducting information warfare against them. Criticism of Putin doesn’t seem to be sticking to the leader as hoped, but taken on as a threat to the wider Russian population. Moreover, far from being ashamed of their country, 86% are proud to be living in Russia and 81% have never thought of moving abroad. If an aim of increased efforts to counter Russian propaganda is to sway Russian audiences, messaging and efforts must fit within their existing values and perceptions.Criticism will not have the desired effect of turning Russians against Putin, for example, but pushing Russians closer to him.

Likewise, attempting to counter disinformation with so-called “myth-busters” will do little to change the minds of those who already accept propaganda as truth. Setting aside the mathematical challenges of disproving disinformation with proof otherwise (it takes far less time to create and spread lies than it does to prove them wrong), fighting lies with facts actually does little to change perspectives.Moreover, those people exposed to disinformation are seldom those who view the corrective information when it comes out.

Criticism might have its place among audiences already disaffected, but it most certainly is not a viable strategy should the target populations already be sympathetic to the opponent.

The World is Not a Target Market

One of the biggest weaknesses in current approaches to countering propaganda is an inability to break audiences down into highly targeted subsets – instead viewing audiences as monolithic groups. The problem with this is, the less you define and know your audience, the less likely your message is to succeed in shaping opinions among them.

In Senator Portman’s speech introducing the new legislation, he cites diverse propaganda threats coming from China, Russia and Daesh, all potentially leading Americans astray with disinformation, but also manipulating undefined “local communities”. The U.S. alone is far from a monolithic audience, all sharing the same values and beliefs – never mind the untold populations living closer to the source of such propaganda. Treating these broad audiences in the same way, with the same messaging is doomed to fail.

In order to sway an audience, any counter messaging must conform to that target group’s existing beliefs. If new information contradicts what a group already believes – even if a superior argument is presented – it is unlikely to be accepted. Likewise, counter propaganda that denigrates or insults the target audience will actually have the adverse effect, causing people to more fervently believe what they did before. And, if the audience does not like the messenger, they will not accept the message. In short, it is far easier to reaffirm existing beliefs, than it is to change perspectives, and much comes down to the messenger as well as the message.

Would-be counter-propagandists hoping to have an impact should take care to identify and differentiate audiences to avoid failure. Crafting strategic communications campaigns that successfully engage and sway populations requires deep insight into well-defined target audiences. The world is not a target market.

Banning Information Makes it Sexy

There has been much recent talk about engaging industry to help supress extremist propaganda such as that disseminated by Daesh. While that might seem like a viable strategy, banning information actually makes it more attractive – regardless of its nature.

As Dr. Robert B. Cialdini noted in his book Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion, banning information will only make people want to access it, and be more inclined to believe its message. In studies of court cases where a judge instructed the jury to disregard evidence, the jurors actually valued that forbidden information more. Humans want what they cannot have as a result of the scarcity heuristic, another cognitive bias.

The West has benefited from having had its broadcasts banned by others in the past. Voice of America programs were banned in the Soviet Union and were, thus, that much more coveted by audiences behind the Iron Curtain. Take heed from past successes, ban content sparingly, if at all. Such scarcity can have the adverse affect than what was intended.

Beyond the Bill: Think Differently

The changed media environment demands innovative and new solutions. Avoid hasty, reactionary measures, such as banning information. Focus on strategic, data-driven approaches that build long-term capacity.

The Curtain Has Dropped: It is Time for a re-brand

Using Voice of America/Radio Free Europe to counter modern propaganda is taking a Cold War measure and applying it in a Digital Age. Not only is the brand strongly associated with Cold War efforts, news media are changing. If the aim is to build on existing infrastructure, then it is time for a re-brand.

Consider the examples of both RT and AJ+ – two foreign media outlets that target an American audience. Both have attempted to gain traction in markets abroad under different, more obvious brand names: Russia Today and Al Jazeera. They both produced news, with the aim of showing a different perspective – namely that of their respective homeland’s – on current events. To that end, neither was overly successful, that is, until they re-branded and began to produce shorter, punchier content.

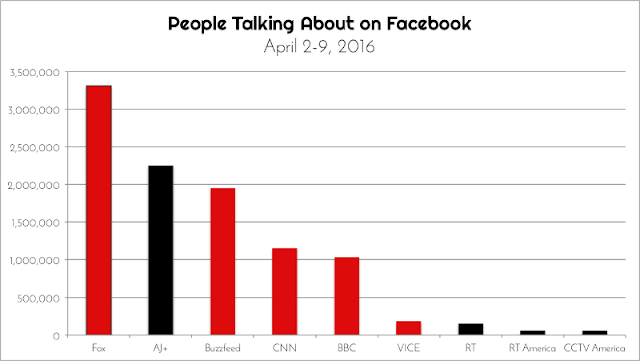

Arguably, one has had greater success than the other. After following RT’s example and shortening its name to AJ+, the Qatar-funded media initiative began producing catchy videos on hot socio-political topics, ultimately catapulting the mobile-centric outfit to rank among the top 10 Facebook video publishers on the social network, with 1.4 million video shares in June 2015, according to Newswhip. AJ+ alone stands out among a Facebook comparison of American versus foreign news outlets being “talked about” on the social network (see Fig.1). And AJ+ has endured, while its sister organisation Al Jazeera America has shut down.

Figure 1: People Talking About News Outlets on Facebook

Like RT, AJ+ videos focus on controversial issues widely ignored by mainstream media, such as police brutality, racism, and poverty – embodying its tagline of “Experience. Engage. Empower.” And in an analysis of likes between Facebook Pages, both outlets appear to be creating networks beyond the more traditional “ego network” typical of media giants such as the BBC, instead directly engaging with protest movements such as Occupy (RT) and Human Rights Watch (AJ+).

Given the success of AJ+, and to a lesser degree RT (insomuch as it has been able to stir such fear among political leaders), there is a model here in re-branding to fit a Digital Age. For Voice of America to remain a relevant tool in this changed information environment, it must create a new identity (and content) that fits with the times and disassociates with pre-existing Cold War notions.

Know Thy Audience

All audiences are not the same. There are no blanket approaches to influencing both domestic and foreign audiences. In fact, each audience must be approached very differently. While messaging should be consistent, as the Internet has flattened communications (a domestic audience can now easily access what a foreign audience might consume), each market is unique, but not isolated.

The Russians (and indeed, Daesh) understand the value of focused messaging to smaller, defined target audiences. While their communications approaches differ for internal and external audiences, the Russians know that not all foreign audiences are the same. How they aim to inform and persuade Georgians, for example, is quite different from how they go about swaying Americans. Moreover, it is not about vaguely projecting Russian values, but achieving some more tangible ends whether that is to acquire more territory, to reinforce a claim of media bias against Russia in international coverage, or destabilize opponents. If the West aims to counter this level of information warfare, it will need to take a page from the Russian manual.

Digital Media Mapping

The Internet has made it possible to gather detailed information on media landscapes. Digital Media Mapping is the monitoring and analysis of interactions between people to essentially understand how people are communicating online and about what. Such analysis can help identify who is engaging online and what topics they are discussing, but also how these subjects are being discussed, or the sentiment around it. Digital Media Mapping helps frame online engagement, by determining where people are connecting be it by geo-location (when data is available) or by the online spaces where interactions occur (such as forums, social networks or media comment sections). Most importantly, however, Digital Media Mapping can help explain why these interactions are important, identifying networks and key influencers.

Such in-depth mapping can provide ample data stemming from the country-specific cultural, sociological, economic and political domains, and inform the development of a facts-based communications strategy that can hyper-target influencers, engaging them to help build an amplification network of supportive voices – but also to create strategies for countering opponents.

Engage Like-minded Communities – Build Capacity

Sharing the stage at the Atlantic Council conference with Senators Murphy and Portman was Kristin Lord, CEO of IREX, an American “non-profit organisation providing thought leadership and innovative programs to promote positive lasting change globally.” She noted that “whether it is counter-propaganda, whether it is counter-extremism, we just really have to come to terms with the fact the United States government is not always the most credible voice in these debates. So we have to invest in the people who are making the credible arguments.” While Lord is quite accurate in that statement, such support must go beyond financial aid (and even that money trail should be considered and hidden lest it impact credibility.)

It is not enough to support local voices financially; in many cases they need significant capacity building. Take Georgia, for example, a small country wedged between Russia and Turkey.

Georgia has long courted Western integration – be it with the European Union or NATO. But the country’s aspirations seem always to be delayed. A disastrous war with Russia in 2008 has left Georgia in a precarious situation. With two breakaway regions, Abkhazia and South Ossetia, now de facto Russian vassal states, Georgia’s unresolved territorial disputes with both threaten any potential integration with the West. Moreover, the country’s proximity to Russia makes it extremely difficult for Western allies to defend it– indeed, Georgia was left widely unsupported in the short 2008 war. While a significant percentage of the population remains Western-leaning, other camps are swayed by Russian influence. Pouring money into supporting local voices sympathetic to Western views will not be enough to counter Russian propaganda and disinformation.

Georgian media has advanced since the fall of the Soviet Union, yet it struggles to hold the government accountable or to reasonably inform citizens. Individuals close to the political elite or with their own political ambitions own the major media outlets. Many of these owners have strong business ties with Russia and thus are prone to external influence. Cultural challenges also plague the Georgian media. Journalists have struggled to “unlearn” Soviet ways and thus fail to distance themselves from the political class. Georgia’s media landscape, political debates and public opinion are also increasingly being influenced and shaped by the rapid growth in online digital information and social media use. Understanding the scope and depth of these changes and their implications for consolidating Georgian democracy and the country’s economic and political security and stability is critical.

Digital insights can empower citizen journalists, independent media and civil society to amplify their messaging to inform the public and better hold the government to account – however, capacity must also be built among these networks such that they stand a chance of countering Russian propaganda. Comprehensive training on communicating in a Digital Age and coping with disinformation must be offered. Venues and opportunities for collaboration must be established and fostered to develop a network that can share information, and increase the volume of counter-propaganda efforts. It is not enough that these beneficiaries be enabled to share a message, but that they know how to make it heard, spread farther, and feed back into a network with shared aims and goals. Moreover, in an environment where Russia is not viewed as an enemy, simply criticizing the opponent is not a sophisticated enough strategy for countering propaganda, as it further polarises an already fractured society. Careful crafting of alternative messaging must take into account the socio-political and psychological realities of key target audiences, and the country as a whole.

Establish An Institute on Influence

While the creation of the “Center for Information Analysis and Response” to coordinate all counter-propaganda efforts is required, more research on the effects of disinformation and influence is needed. Propaganda has long been a dirty word in the English language. Few people study the topic, and research is diffused among psychology, sociology, political science and communications departments at universities. For the most part, any programs focusing on the subject do so in an historical context, which while still necessary does not foster the urgent and necessary skillsets required for countering propaganda in a Digital Age.

Those with practical skillsets in influence (political campaign specialists, marketers, or public relations practitioners) tend to work in short, focused bursts (an election, an ad campaign, or lobbying on a single issue), which, while applicable, is not the systemic approach that counter-propaganda demands. Entrusting such professionals to devise an information campaign that consists of half-truths and is repeated often may achieve the short-term effect of positioning Putin, for example, as the boogeyman at home, but certainly does nothing to win over Russian audiences. Moreover, these professional communicators are likely to have worked in single or similar markets, meaning their approaches are not directly transferrable to other audiences – what might work in the U.S.A. doesn’t necessarily apply in Kazakhstan, for example.

More research and analysis must be conducted on how information shapes perspectives and behaviours in an online environment. Researching the spread of messages and ideas through the Internet, and how target audiences adopt them, a dedicated “Institute on Influence” might seek to understand better how minds and actions are shaped in a Digital Age.

Media, information, and technology are converging in ways that significantly impact behaviour and perspective. A new multidisciplinary approach is required to analyze how this changing information environment is shaping human perspective and how it is shaped in return. An Institute on Influence could bring together creative minds from a variety of fields including computer science, behavioural psychology and strategic communications to study the online information environment determining methods and trends in opinion shaping. In developing methodology and tools for studying the spread and impact of messages on target audiences, such an institute would also identify techniques for effective strategies in a Digital Age that can then be applied to develop effective counter-propaganda measures.

A Good First Step – But Strategy Demands More

Countering propaganda in a Digital Age is daunting. As noted in the introduction to this article, the “Countering Foreign Propaganda and Disinformation Act” is a good first step. Modern propaganda and disinformation, however, cannot be fought with coordination and funding alone, we desperately need new approaches that take into account the rapidly changing information environment. A multidisciplinary and systemic approach is necessary – and at each step an understanding for how quickly the information we put out there can be turned against us is crucial. To win this information war, we must begin to think differently.

About the Author: