During negotiations for the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), military activities in another state’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) were a point of contention. Currently, the issue remains controversial in state practice. UNCLOS attempts to balance the differing interests of coastal and maritime states, but is silent or ambiguous on the legality of military operations in foreign EEZs.

By Jing Geng

On December

10, 1982, in Montego Bay, Jamaica, United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) was presented for signature. Over 115

countries signed that same day.[1] UNCLOS came into force on November 16, 1994,

and has been broadly accepted by the international community.[2]To date, 161

States and the European Union have joined the convention.[3]

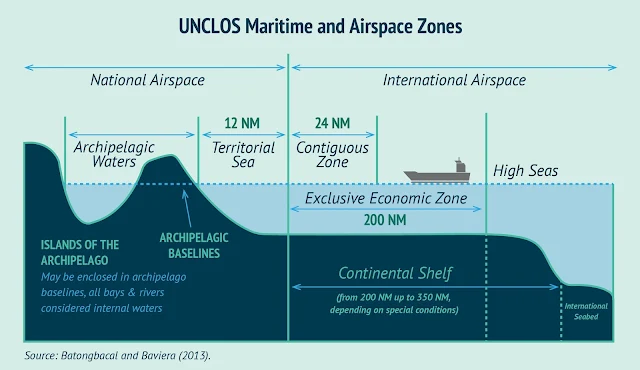

Image Attribute: UNCLOS Maritime and Airspace Zones /

Source: Batongbacal and Baviera (2013) via AMTI CSIS

UNCLOS is a

comprehensive treaty that creates a legal regime governing the peaceful use of

the ocean and its resources.[4] UNCLOS provides guidance on various maritime

matters such as pollution, environmental protection, and resources rights.[5] In

many ways, UNCLOS has provided clarity and reliability in the maritime

context,[6] however, it is either silent

Development of Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ):

In some ways,

the law of the sea has always had a tension between states supporting the

doctrine of an open sea (mare liberum) and states that seek control over a more

closed sea (mare clausum).[9] This struggle has been continuous throughout the

evolution of the law of the sea and many UNCLOS provisions reflect this balance

between coastal state and maritime state interests.[10]

UNCLOS

provides for different maritime zones with varying substantive regimes. For

instance, the coastal state has sovereignty over the territorial sea,[11] which

extends up to 12 nm from the baseline.[12] Foreign warships must follow the

conditions of Article 19 for ‘innocent passage’ if they are to navigate through

the territorial seas of a coastal state.[13] Article 25 permits the coastal state

to protect itself and ‘take the necessary steps in its territorial sea to

prevent passage which is not innocent.’[14] On the other hand, all states equally

enjoy the freedom of navigation and overflight in the high seas,[15] an area beyond

national jurisdiction.[16] Situated between these two substantive regimes is the

EEZ, which is arguably the most complicated of the maritime zones in terms of

regulation and enforcement.[17]

The concept of

an EEZ developed early in the course of negotiations during the third United

Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS III).[18] Asian and African states

adopted the 1972 Addis Ababa Declaration recognizing the right of a coastal

state to establish an EEZ up to 200 nm in which ‘the coastal state would

exercise permanent sovereignty over all resources without unduly hampering

other legitimate uses of the sea, including freedom of navigation, of

overflight and laying cables and pipelines.’[19] During UNCLOS III, there was

considerable debate regarding the EEZ’s legal status.[20] Maritime powers

maintained that the EEZ should have the traditional freedoms of the high

seas,[21] while coastal states argued for more rights and control over the

zone.[22] The result is an EEZ that is a compromise between the varying

positions.[23]

UNCLOS Article

56 establishes the substantive regime of the EEZ. This maritime zone begins

where the territorial sea ends and is to extend no more than 200 nm from the

baseline.[24] The coastal state has the sovereign rights for the economic

exploitation and exploration of all resources in the EEZ, including, for

instance, energy production.[25] The coastal state also has jurisdiction over

artificial islands and installations, marine scientific research, and the

protection and preservation of the marine environment.[26] In its regulation of

the EEZ, the coastal state is obliged to give ‘due regard’ to the rights and

duties of other states and must act in a ‘manner compatible’ with the

Convention.[27] It is important to note that ‘sovereign rights’

Varying State Interpretations:

Since the

conclusion of UNCLOS in 1982, the general concept of an EEZ and the right for a

coastal state to exercise sovereign rights over economic activity and resources

have become customary international law.[33] However, as a relatively new concept

in international law, the specific scope of rights and responsibilities in the

EEZ is dynamic and ever-evolving.[34] UNCLOS does not clarify the specific issue

of military activities in the EEZ and a major source of contention continues to

be whether maritime states may unilaterally conduct certain military operations

in the EEZ of the coastal state without permission.[35] Some maritime powers

support unfettered military activity in the EEZ by emphasizing the freedom of

navigation.[36] Conversely, some coastal states object to military activity in

their EEZ by expressing concern for their national security and their resource

sovereignty.[37] This divergence in perspective regarding the legality of foreign

military activities in the EEZ is partly due to varying interpretations of Article

58, which permits maritime states to engage in ‘other internationally lawful

uses of the sea related to these freedoms, such as those associated with the

operation of ships, aircraft and submarine cables and pipelines, and compatible

with the other provisions of this Convention.’[38] Thus, nations such as the

United States perceive this provision to permit naval operations in the EEZ as

an activity ‘associated with the operation of ships’ and more generally, as

protected within the scope of the freedom of navigation.[39]

Since UNCLOS

is meant to be a comprehensive ‘package deal’, states may not make reservations

or exceptions to the Convention.[40] Otherwise, parties to the treaty could

effectively opt out of their convention obligations.[41] Under Article 310,

States retain the right to make declarations, though such statements are

illegitimate if they ‘purport to exclude or to modify the legal effect of the

provisions of this Convention in their application to that State.’[42] Some

states have exercised their Article 310 right by making declarations on the

issue of military activities in the EEZ.[43] For instance, Brazil, Bangladesh,

Cape Verde, Malaysia, India, and Pakistan have all expressed concern over the

ability of foreign military vessels to engage in certain activities within the

EEZ.[44] In their declarations, these states require consent before a foreign

ship may conduct military activities.[45] To illustrate, Brazil declared in 1988:

The Brazilian

Government understands that the provisions of the Convention do not authorize

other States to carry out military exercises or manoeuvres, in particular those

involving the use of weapons or explosives, in the exclusive economic zone

without the consent of the coastal State.[46]

States such as

Italy, Germany, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom have protested these

interpretations as unduly restrictive on navigational freedoms and as

inconsistent with Article 310 and UNCLOS.[47] For example, the Netherlands

declared in 1996:

The Convention does not authorize the

coastal State to prohibit military exercises in its exclusive economic zone.

The rights of the coastal State in its exclusive economic zone are listed in

article 56 of the Convention, and no such authority is given to the coastal

State. In the exclusive economic zone all States enjoy the freedoms of

navigation and overflight, subject to the relevant provisions of the

Convention.[48]

These

declarations demonstrate the sharp disagreement and variance in interpretation

regarding the legality of conducting military activities in the EEZ of another

country.[49]

Despite the

ambiguity in the language of UNCLOS and the divergence in interpretation of the

text, there is some evidence that the Convention did not intend to broadly

exclude peacetime military operations in the EEZ.[50] For instance, the 1949

International Court of Justice (ICJ) Corfu Channel decision refers to the

freedom of navigation of warships in peacetime as a ‘general and

well-recognized principle.’[51] The ICJ’s findings in the Corfu Channel case were

influential in the development of the law of the sea in the UNCLOS

conferences.[52] This finding is crucial since the freedom of navigation is the

foundation for military operations at sea.[53] However, the Court’s decision did

not specify the scope of the rights included in the freedom of navigation of

warships. During UNCLOS III, the President of the Conference, Tommy T.B. Koh,

commented on the question of military activities in the EEZ by stating in 1984:

The solution in the Convention text is very

complicated. Nowhere is it clearly stated whether a third state may or may not

conduct military activities in the exclusive economic zone of a coastal state.

But, it was the general understanding that the text we negotiated and agreed

upon would permit such activities to be conducted. I therefore would disagree

with the statement made in Montego Bay by Brazil, in December 1982, that a

third state may not conduct military activities in Brazil’s exclusive economic

zone[…].[54]

Unfortunately,

the issue of military activities in the EEZ remains ambiguous and unsettled.

“For Peaceful” Purposes:

UNCLOS

repeatedly emphasizes that various maritime activities should be conducted ‘for

peaceful purposes.’[55] Both the Preamble and Article 301, for instance,

reinforce the peaceful uses of the oceans.[56] Article 301 for ‘Peaceful uses of

the seas’ echoes Article 2(4) of the United Nations Charter by stating:

In exercising their rights and performing

their duties under this Convention, States Parties shall refrain from any

threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political

independence of any State, or in any other manner inconsistent with the

principles of international law embodied in the Charter of the United

Nations.[57]

Although some

states have interpreted Article 301 to prohibit foreign military activities in

the EEZ,[58] it does not follow that military activities are inherently

non-peaceful. While Article 88, for example, reserves the high seas for

peaceful purposes,[59] military maneuvers and exercises have traditionally been considered

compatible with the freedom of the high seas.[60]

Due Regard’ for Rights and Duties

In tandem,

Articles 56 and 58 mandate that coastal and maritime states shall mutually

respect each other’s rights and duties in the EEZ.[61] These articles are meant

to balance the interests of various states in the EEZ. However, ‘due regard’ is

not defined in the Convention and is open to interpretation.[62] For instance,

proponents of the legality of military activities in the EEZ argue that such

actions do not interfere with the economic activity of a nation and thus cannot

be regulated by the coastal state.[63] What regard is due will inevitably depend

on the circumstances, for instance, a military vessel conducting weapons tests

may need to take measures to ensure the safety of maritime navigation in the

vicinity.[64] In cases where the extent of a state’s legal rights in the EEZ is

uncertain, Article 59 provides that the conflict in interests ‘should be

resolved on the basis of equity and in the light of all the relevant

circumstances, taking into account the respective importance of the interests

involved to the parties as well as to the international community as a

whole.’[65] Thus, circumstances matter and the implication is that there are many

variables in determining whether certain military activities are permissible in

the EEZ of a state, such as the scope and nature of the activity, the proximity

of the vessel to the coastal state, and the impact on the marine environment.

About The Author:

Jing Geng, Utrecht

University School of Law, LL.M. Candidate Public International Law (2012);

Washington University School of Law, J.D. (2011); Washington University College

of Arts & Sciences, B.A. Psychology (2008).

Publication Details:

This article is an excerpt from a technical paper, titled “The Legality of Foreign Military Activities in the Exclusive Economic Zone under UNCLOS” published at Merkourios 2012 – Volume 28/Issue 74, Article, pp. 22-30. URN: NBN:NL:UI:10-1-112848 ISSN: 0927-460X URL: www.merkourios.org Publisher: Igitur, Utrecht Publishing & Archiving Services Copyright: this work has been licensed by the Creative Commons Attribution License (3.0)

Download The Paper - LINK

References:

[1] JA Duff,

‘The United States and the Law of the Sea Convention: Sliding Back from

Accession and Ratification’ (2005) 11 Ocean and Coastal LJ 1, 6.

[2] United

Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea – Current Status accessed

30 January 2012.

[3] United Nations

Convention on the Law of the Sea – Current Status (n 10).

[4] United

Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, 10 December 1982, 1833 UNTS 397

Overview and full text accessed

30 January 2012.

[5] DG

Stephens, ‘The Impact of the 1982 Law of the Sea Convention on the Conduct of

Peacetime Naval/Military Operations’ (1998) 29 Cal W Int’l LJ 283.

[6] ibid.

[7] ibid.

[8] M Lehto,

‘Restrictions on Military Activities in the Baltic Sea – A Basis for a Regional

Regime?’ (1991) 2 Finnish YB Int’l L 38, 45; see also art 88 United Nations

Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) 10 December 1982, 1833 UNTS 397.

[9] CE Pirtle,

‘Military Uses of Ocean Space and the Law of the Sea in the New Millennium’

(2000) 31 Ocean Dev and Int’l L 7, 11.

[10] ibid.

[11] Subject to

the right of innocent passage and transit passage of foreign vessels. See

UNCLOS, Arts 17 and 38 respectively.

[12] UNCLOS, Art

3.

[13] UNCLOS, Art

19.

[14] UNCLOS, Art

25.

[15] UNCLOS, Art

87.

[16] UNCLOS, Art

89.

[17] See eg, DR

Rothwell and T Stephens, The International Law of the Sea (Hart Publishing,

Portland 2010) 428.

[18] S Mahmoudi,

‘Foreign Military Activities in the Swedish Economic Zone’ (1996) 11 Int’l J

Marine and Coastal L 365, 366.

[19] ibid 367.

[20] ibid 366.

‘Since the advent of the EEZ in 1971 there has been contrast in the views of

different states about the legal status of the zone, the balance of rights and

duties, and particularly about the exercise of the so-called residual rights

i.e. the rights which are not expressly attributed in the convention either to

the coastal state or the flag state. It is not surprising, therefore, that the

relevant provisions in the 1982 LOS Convention are not interpreted uniformly.’

[21] GV

Galdoresi and AG Kaufman, ‘Military Activities in the Exclusive Economic Zone:

Preventing Uncertainty and Defusing Conflict’ (2001) 32 Cal W Int’l LJ 253,

254, ‘It is not a part of the high seas, although high-seas-like freedom exists

there with respect to navigation. EEZ claims extract approximately 30 to 36 per

cent of the world’s oceans from waters traditionally considered high seas.’

[22] Commander

JC Meyer, USN, ‘The Impact of the Exclusive Economic Zone on Naval Operations’

(1992) 40 Navak L Rev 241.

[23] ibid 241.

[24] UNCLOS, Art

57.

[25] UNCLOS, Art

56.

[26] UNCLOS, Art

56.

[27] UNCLOS, Art

56.

[28] Pirtle (n

17) 30.

[29] Lehto (n

16) 48.

[30] UNCLOS, Art

58.

[31] UNCLOS, Art

58(2).

[32] JM Van

Dyke, ‘Military ships and planes operating in the exclusive economic zone of

another country’ (2004) 28 Marine Policy 29, 36.

[33] Galdoresi

and Kaufman (n 29) 285.

[34] ibid 254.

[35] Rothwell

and Stephens (n 25) 284.

[36] See eg, the

United States Navy’s Freedom of Navigation Program as described in WJ Aceves,

‘The Freedom of Navigation Program: A Study of the Relationship Between Law and

Politics’ (1995) 19 Hastings Int’l & Comp L Rev 259.

[37] M Valencia,

‘Intelligence Gathering, the South China Sea, and the Law of the Sea’

(Nautilius Institute, 30 August 2011) accessed

30 January 2012. See also MJ Valencia and Y Amae, ‘Regime Building in the East

China Sea’ (2003) 34 Ocean Dev and Int’l L 189.

[38] UNCLOS, Art

58(1).

[39] Y Song,

‘The PRC’s Peacetime Military Activities in Taiwan’s EEZ: A Question of

Legality’ (2001) 16 Int’l J Marine and Coastal L 625, 635, ‘Specifically, the

U.S. interprets UNCLOS Art 58(1) to permit “military activities such as task

force maneuvering, flight operations, military exercises, naval survey,

information gathering, and weapons testing and firing.”’ ibid 636.

[40] UNCLOS, Art

309.

[41] Van Dyke (n

40) 30.

[42] UNCLOS, Art

310.

[43] UNCLOS, Art

310 for ‘Declarations and statements’, ‘Article 309 does not preclude a State,

when signing, ratifying or acceding to this Convention, from making

declarations or statements, however phrased or named, with a view, inter alia,

to the harmonization of its laws and regulations with the provisions of this

Convention, provided that such declarations or statements do not purport to

exclude or to modify the legal effect of the provisions of this Convention in

their application to that State.

[44] See

generally United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea: Declarations and

Statements accessed

30 January 2012.

[45] UNCLOS

Declarations and Statements (n 52).

[46] Brazil

(1988), UNCLOS Declarations and Statements (n 52).

[47] UNCLOS

Declarations and Statements (n 52).

[48] The

Netherlands (1996), UNCLOS Declarations and Statements (n 52).

[49] Van Dyke (n

40) 29.

[50] Van Dyke (n

40) 31.

[51] Case

concerning Corfu Channel (United Kingdom v Albania) [1949] ICJ Rep 4.

[52] Rothwell

and Stephens (n 25) 267-68: ‘The ICJ’s finding that the freedom of navigation

was enjoyed by warships in peacetime was subsequently reflected in

deliberations at UNCLOS I and III and in both the Geneva Conventions and the

LOSC […]. That it was considered a general principle further elevates its

significance and needs to be taken into account when interpreting the

international law of the sea concerning navigation by warships.’

[53] ibid 267.

[54] Van Dyke (n

40) 31.

[55] Rothwell

and Stephens (n 25) 266: ‘This is reflected not only in Article 301, but is

restated in numerous provisions throughout the convention including that the

high seas are reserved for peaceful purposes (LOSC, Art 88), that the use of

the Area is exclusively for peaceful purposes (LOSC, Art 141), and that marine

scientific research is to be carried out exclusively for peaceful purposes

(LOSC, Art 240). Consistent with these articles and the Preamble, the

convention also emphasizes that passage in the territorial sea which is

‘prejudicial to the peace’ is inconsistent with the LOSC and coastal states may

respond accordingly (LOSC, Art 19).’

[56] UNCLOS (n

16) Preamble: ‘Recognizing the desirability of establishing through this

Convention, with due regard for the sovereignty of all States, a legal order

for the seas and oceans which will facilitate international communication, and

will promote the peaceful uses of the seas and oceans, the equitable and

efficient utilization of their resources, the conservation of their living

resources, and the study, protection and

preservation of the marine environment.’

[57] UNCLOS (n

16) Art 301. See also Art 2(4) United Nations, Charter of the United Nations

(24 October 1945) 1 UNTS XVI.

[58] UNCLOS

Declaration and Statements (n 52).

[59] UNCLOS (n

16) art 88.

[60] Valencia (n

45). See also Francesco Francioni, ‘Peacetime Use of Force, Military

Activities, and the New Law of the Sea’ (1985) 18 Cornell Int’l LJ 203, 222:

‘The term ‘peaceful purposes’ did not, of course, preclude military activities

generally. The United States had consistently held that the conduct of military

activities for peaceful purposes was in full accord with the Charter of the

United Nations and with the principles of international law. Any specific

limitation on military activities would require the negotiation of a detailed

arms control agreement.’

[61] UNCLOS (n

17) Arts 56 and 58.

[62] Galdoresi

and Kaufman, (n 29) 273: ‘As agreed upon, however, with residual rights

unassigned and the issue left in the balance, and with each side required to

exercise its rights in the EEZ with due regard for the rights of the other, the

regime appeared ambiguous. These provisions left any undefined rights

unassigned, and gave no hint as to how to weigh the balance in settling any

dispute over such assignment. Moreover, these provisions, while requiring ‘due

regard,’ did not define just what regard is due, leaving that difficult and

dangerous question on the table, with the answer very much dependent upon the

eye of the beholder.’

[63] Meyer (n

30) 246: ‘[A]rticle 58’s stipulation that states “shall comply with the laws

and regulations adopted by the coastal State” in its EEZ, relates to activities

for which the coastal state exercises sovereign rights and jurisdiction under

the provisions of part V of the 1982 Convention relative to the EEZ. Those

activities are economic in nature and are not applicable to the conduct of

warships in the coastal state’s EEZ.’

[64] Rothwell

and Stephens (n 25) 280.

[65] UNCLOS (n

16) Art 59