Meghaduta (cloud messenger) is a Sanskrit poem written (c. 400 CE) by Kalidasa, considered one of the greatest Indian poets, about a message of love carried by a cloud to the Himalayas. This poem served as the code-name of the military operation launched by India to gain control over the ridges adjacent to the Siachen glacier.

By Ravi Baghel and Marcus Nüsser

Department of Geography, South Asia Institute, Heidelberg University

Cluster of

Excellence: Asia and Europe in a Global Context, Heidelberg, Germany

Meghaduta

(cloud messenger) is a Sanskrit poem written (c. 400 CE) by Kalidasa,

considered one of the greatest Indian poets, about a message of love carried by

a cloud to the Himalayas. This poem served as the code-name of the military

operation launched by India to gain control over the ridges adjacent to the

Siachen glacier. There was dark humour in the choice of the code-name, as

Operation Meghdoot, launched on 13 April 1984, consisted of Indian air force

helicopters carrying assault troops to the area to obtain control of key ridges

and passes. Pakistan had also planned Operation Ababeel to capture the same

ridges, but the Indians came to know of it and moved first. The attack of the

Pakistanis was unsuccessful as by then the Indians already held the commanding

positions on the passes (Musharraf, 2007, pp 68-69).

Even though it

has been presented at times as the first military incursion into the area,

there had been military activity prior to this. The Indian air force first

landed helicopters on the glacier in 1978 (Ministry of Defence, 2014). The

Indian army moved a large number of troops on foot to the base of the Siachen

glacier in 1983, and they had been trained for several weeks to be able to

fight there (Indian Army, 2014). The Indian General in charge of the operation,

acknowledged that he had been one of a small group of influential officers who

had begun lobbying for an aggressive Indian policy on Siachen already in the

late 1970s. However he stated that operation was intended to be just a show of

force, and not the permanent occupation that it later became (Wirsing, 1995,

pp. 208-209).

The initial

plan was to deploy troops to three passes on the Saltoro range that controlled

access to the Siachen glacier, from north to south, Sia La, Bilafond La and

Gyong La (Fig. 1). However, after these positions were secured, the two armies

began to compete to gain higher ground nearby.

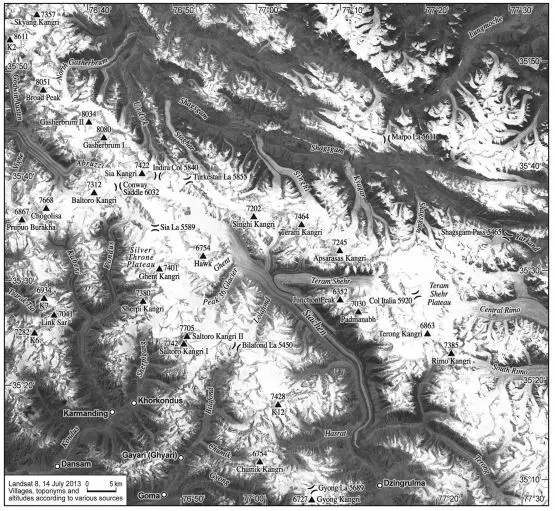

Map Attribute: Satellite

image with toponyms, altitudes and villages of area surrounding Siachen

glacier. The 71 km long glacier runs diagonally from top left at Indira Col to

its snout near Dzingrulma, the last Indian military camp. The Indian Army

positions run along the Saltoro ridge, west of the glacier, along a line

connecting Indira Col, Sia La, Bilafond La and Gyong La. The Pakistan Army has

camps at Goma and Gyari and access over the Baltoro glacier to the Conway

Saddle and glaciers in the southwestern part. The area controlled by China is

located north of the ridge from K2 to the Teram Shehr plateau.

The belief

that if one side did not capture a height then the other would, led to the

militarization of the entire ridge-line. This rapidly increased the number of

troops required by the Indian army to hold the commanding positions, and made

the logistics of the operation even more complex. This large deployment combined

with a sophisticated logistic chain created the fear that India might attack

the Northern Areas (since 2009 called Gilgit-Baltistan) territory of Pakistan,

which ended up escalating the number of Pakistani soldiers in turn (Raghavan,

2002, pp 41-43).

In spite of

previous training, the extreme cold and high altitude produced very high

casualty figures. Of the 29 Indian soldiers who landed at Bilafond La, one had

to be immediately evacuated. Another soldier died on the second day of High

Altitude Pulmonary Edema (HAPE), and 21 of the remaining suffered frost bites

(Gokhale, 2014). Many of the medical conditions that developed at such high

altitude could not even be diagnosed at first, and it was only after 1986 that

some of the conditions and ways of dealing with them became known (Anand,

2001). The Pakistani army termed the psychological effect of fighting at high

altitude “Siachen syndrome”, describing the progressive change in personality

of its soldiers at such extreme altitudes from normal to selfish, then

introverted and finally irrational (Ali, 1991, p. 12).

India had been

conducting research on high altitude mountain warfare since its defeat in the

1962 war against China, much of which was fought in the Himalayas. As part of

this a 200 bed hospital specialised in high altitude medicine, which is today

the main hospital supporting Indian troops on Siachen, had been set up in Leh

shortly thereafter (Bewoor, 1968). The “High Altitude Warfare School” was

established at the same time and created a large cadre of well trained military

mountaineers. This also meant that Indian climbing expeditions almost always

included army officers (Sircar, 1984; Raghavan, 2002, p. 32). This military

presence in fact was one reason why Pakistan was extremely suspicious of Indian

mountaineering expeditions that had entered the Siachen area (Khan, 2001, p.

224). Another reason India was willing to station troops around the year,

unlike Pakistan, was that it already had soldiers with experience in the

extreme conditions of Antarctica. The preparations for the first year round

occupation of the Indian Antarctic research station, Dakshin Gangotri, began in

December 1983, with the construction and scientific team primarily consisting

of people drawn from the Indian army (Stewart, 2011, p. 384). These same

officers were subsequently in charge of organising the training and logistics

for the year-round occupation of the Siachen glacier (Sharma, 2001, pp.

209-303).

As early as

1993, the hot war initiated by Operation Meghdoot began to become a frozen

conflict. Wirsing (1995) quotes a general of the Indian army summing up the

military situation at that time:

“Environmental

casualties … were down dramatically e by 90 percent e to a rate less, than that

of an ordinary military unit elsewhere in the country … there were no fighting

related casualties. The economic costs of Siachen were routinely inflated by

the media; India … could bear them indefinitely” (Wirsing, 1995, p. 214,

emphases in original).

A total of 846

Indian soldiers have died in the conflict between 1984 and 2012 according to

official figures (Ministry of Defence 2012). However, the casualties have

varied over the years and other estimates are that the Indian army lost around

30 soldiers per year till 2003, when a ceasefire began, after which fatalities

reduced to around 10 deaths per year, and subsequently to 4 per year (Pubby,

2008). This significant reduction in number of casualties is one reason the

Indian Army did not feel compelled to withdraw from the glacier (Thapar, 2006).

This

complacence of the Indian Army regarding the stalemate was challenged by the

Pakistan Army in the Kargil War in 1999, which took place along the LoC. The

possible strategic rationale for this was:

“A Pakistani

nuclear capability would paralyze not only the Indian nuclear decision, but

also Indian conventional forces, and a bold Pakistani strike to liberate

Kashmir might go unchallenged if Indian leadership was indecisive (Cohen, 1984,

p. 153)”.

Pakistan had

become overtly nuclear in 1998; and at the time of this conflict, India was

being run by a minority caretaker government, conditions that fit the above

scenario.

The Kargil War

was planned to be a “reverse Siachen” so that the Pakistan Army would occupy

high mountain positions along the LoC while they were vacated during the

winter, preempting the Indian Army's reoccupation (Tufail, 2009). Although this

would be a violation of the Simla Agreement of 1972, in the Pakistani

perspective, India had already violated it by militarizing the Siachen area.

Pakistan claimed to have no control over the fighters, alleging that they were

Kashmiri freedom fighters. The use of heavy artillery and identity documents on

the corpses of these fighters, made this very unlikely. A taped conversation

between the General in charge of the area, and the Pakistan Army Chief, (later

President) General Musharraf incontrovertibly established that the fighters

were Pakistani soldiers (Swami, 1999, p. 33).

An official

Indian government report on the Kargil conflict also noted the aspect of this

attack being Operation Meghdoot in reverse, but interestingly proposed a

response diametrically opposed to that on Siachen:

“[India] must

not fall into the trap of Siachenisation of the Kargil heights and similar

unheld, unpopulated ‘gaps’ in the High Himalaya along the entire length of the

Northern Border” (quoted in Nair, 2009, p. 37, emphasis added).

This

conclusion perfectly illustrates the dilemma of preemptive occupation of

heights and the logistical problems created as a result of this.

This article is an excerpt from a research paper "Securing the

heights: The vertical dimension of the Siachen conflict between India and

Pakistan in the Eastern Karakoram" Published by

Elsevier Ltd. under the CC BY-NC-ND license

(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Download The Paper - LINK