The need to improve the tools we use to deal with sovereign debt crises has been made particularly urgent by the accumulation of massive public debt stocks and balance sheet vulnerabilities in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis and the 2010 euro-zone crisis (Dobbs et al. 2015).

By Richard Gitlin and Brett House

The need to

improve the tools we use to deal with sovereign debt crises has been made

particularly urgent by the accumulation of massive public debt stocks and

balance sheet vulnerabilities in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis and the

2010 euro-zone crisis (Dobbs et al. 2015).

Following the

failures of Bear Stearns in 2007 and Lehman Brothers in 2008, central banks and

finance ministries pumped massive amounts of liquidity into credit markets to

prevent their breakdown. Concerns raised about Greece’s solvency in late 2009,

and weak activity in many other real economies, resulted in further application

of exceptional monetary and fiscal measures in the ensuing years. As the Bank

for International Settlements (BIS) highlights (BIS 2014a; 2014b), private debt

issuance more or less ground to a halt in 2007 and public debt then expanded

massively, taking the global debt securities market from just over US$60

trillion in 2007 to about US$100 trillion by 2013 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Global Debt Securities Market

(in US$ trillion)

The mountain of

sovereign debt created in recent years leaves little room to cushion the impact

of a policy mistake or respond to a new exogenous shock.Global vulnerabilities

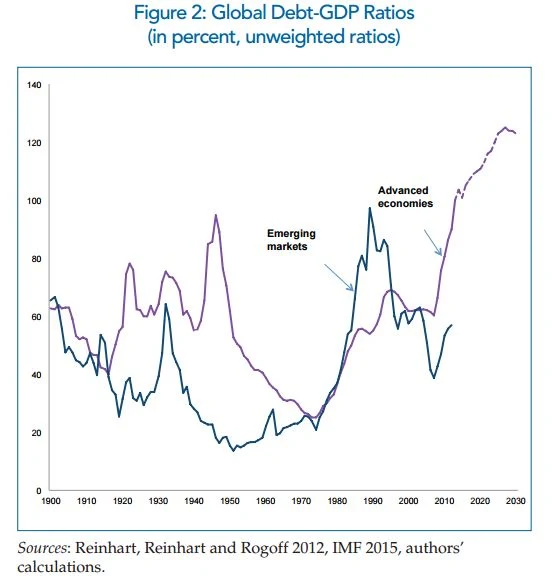

extend far beyond Europe’s continued saga with Greece. The aggregate debt-GDP

ratio for all advanced countries has returned to historic highs above 100

percent (Figure 2) — a level that in the past has been associated with

heightened geopolitical tensions, liquidity problems and insolvency (Reinhart

and Rogoff 2009; 2011; 2013; James 2014).

Figure 2: Global

Debt-GDP Ratios (in percent, unweighted ratios)

This situation is not set to reverse

itself quickly. Globally, real activity is not rebounding strongly as fiscal

stimulus ebbs and investment in public infrastructure falls to new lows

(Summers 2015; Wessel 2015), despite IMF (2014d) evidence that every dollar of

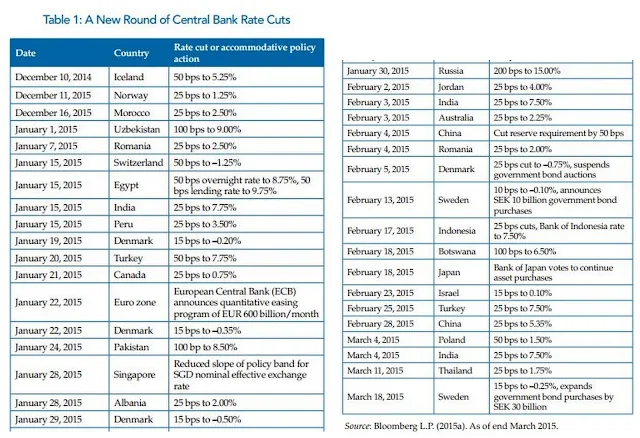

well-planned public investment can increase total output threefold. More than

20 central banks have returned to cutting interest rates and easing monetary

conditions (BIS 2015; also see Table 1). Whether these are genuine responses to

weakness in domestic economies or cloaked attempts to devalue against the US

dollar in a diffuse currency war, uncoordinated monetary easing of this sort

raises the possibility of beggar-thy-neighbour trade protectionism that could

cut global growth prospects further (Rajan 2014).

Table 1: A New

Round of Central Bank Rate Cuts

Medium-term

secular trends imply that heavily indebted developed-economy sovereigns will

not find the years ahead much easier. A gathering imperfect storm of

insufficient stimulus measures, impaired credit-creation mechanisms,

deleveraging across a range of sectoral balance sheets (Koo 2014) and aging

populations could entrench secular stagnation (Summers 2013; 2014a; Lagarde

2015a) and make real debt burdens even more onerous across advanced economies.

The GDP denominator in high debt-GDP ratios is unlikely to bring down these

ratios any time soon. At the same time, there’s little room to pare the debt

numerator.

The IMF (2011b) shows that, ceteris paribus, many advanced countries

would need fiscal surpluses well in excess of recent decanal averages in order

to bring debt-GDP ratios down to 60 percent of GDP from their existing levels

over the next 10 years. Where countries have prepared plans to achieve such

surpluses, they will be technically and politically difficult to execute, as

Barry Eichengreen and Ugo Panizza (2014) underscore. Moreover, if all or even

most advanced countries target fiscal austerity at the same time, global growth

prospects would be dented further and revenue projections would likely not be

realized.

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)

(2013) and IMF (2014b) have projected primary deficits in the neighbourhood of

3.5 percent of GDP over the next five to 10 years, as age-related health,

long-term care and pension spending are set to expand by an average of between

5.5 and 10 percent of GDP in advanced economies (IMF 2012c; 2014a). Running

these projections through a basic model built on the IMF’s debt sustainability

analysis (DSA) template implies that advanced-country debt-GDP ratios could

continue to rise to over 120 percent of GDP by 2030 (see Figure 2).

Past experience

implies that at these debt levels advanced sovereigns would likely face

substantially increased risks of default. As Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff

(2009) show, sovereign debt restructuring has historically been more the norm

than the exception: in nearly any given year over the last century, some

country has been in default or in the process of restructuring its debt. At

current and expected advanced-country debt levels, sovereign debt crises look

nearly inevitable when set against past developments.

Of course, it’s possible

that some combination of tougher capital adequacy standards under Basel III and

related local legislation will stoke demand for near risk-free assets and

sustain bids for new sovereign debt issuance. But it would be deeply imprudent

to orient international economic policy making around this faint hope.

Moreover, as demonstrated by the recent crises in Iceland, Ireland and Spain,

and the late-1990s Asian crisis before them, private-sector debt problems and

balance sheet mismatches can quickly morph into sovereign debt problems.

National accounts likely understate the extent to which corporate

foreign-currency borrowing has expanded through issuance in the domestic

markets of overseas subsidiaries (Shin and Zhao 2013; Wheatley 2014; Nordvig

and Fritz 2014). To paraphrase Reinhart and Rogoff, the next time is unlikely

to be different.

The fact that

much of the recent run-up in advanced country debt is linked to domestic

issuance should provide limited comfort. Although domestically denominated debt

can be inflated away, and debt issued under domestic law is typically easier to

restructure than foreign-law debt, domestic debt can still be a source of

substantial vulnerabilities (Panizza 2007), although these weaknesses may be

less pronounced than those engendered by foreign currency and foreign-law debt

(Dell’Erba, Hausmann and Panizza 2013). Cross-sector and cross-border maturity

and currency mismatches in private and public domestic debt stocks can expose

sovereigns to substantial risks, some of which precipitated sovereign debt

crises in the late 1990s and early 2000s, as detailed by Christoph Rosenberg et

al. (2005).

One of the few

ways in which the next set of sovereign debt crises could genuinely be

different is in the much wider range of countries that could be involved.

Several relatively poor countries, rebranded as “frontier markets,” have in

recent years made their debut issues on international capital markets with

offerings that have been multiple times oversubscribed as investors eschew

meaningful distinctions in credit quality in their search for yield. Ghana was

able to issue an oversubscribed US$1 billion bond in September 2014, one month

after its decision to seek help from the IMF. Even Ecuador returned to capital

markets in 2014 after capricious unilateral defaults in 2008 and 2009 on

international obligations it considered “illegitimate.” Until 2006, South

Africa was the only Sub-Saharan African country that had issued an external

sovereign bond. Since then, 12 Sub-Saharan African countries have issued more

than US$17 billion in external bond debt (see Table 2); three more countries

have made private external placements during this time: Mozambique and Angola

(2012), and Tanzania (2013).

Table 2: African

Frontier Market External Debt Issuance (excluding private placements)

Eight of these African countries had most of their

external debt written off only a few years earlier under the HIPC and

Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative (MDRI) restructuring programs. Some of

these countries are indeed much more credit worthy than they were even a decade

ago: democratic governance, economic performance and natural resource

management have improved markedly in many of them. But all frontier markets

face a substantial risk that they will encounter higher interest rates when it

comes time to roll over their recent bond issues. Even now, some 40 poor

developing countries, many of whom benefited from HIPC and MDRI debt relief,

are in medium to severe debt distress (Table 3; IMF 2014e; Kaiser 2014). The

next debt crisis is already brewing.

Table 3 : Incipient Sovereign Debt Distress in

Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC)

The end of US

quantitative easing (QE) and signals of a coming Federal Reserve rate increase

make efforts to improve the non-system of sovereign debt restructuring

particularly time sensitive (Chung et al. 2014). Although there is evidence

that good policy regimes provide some insulation against taper-induced

pullbacks (Mishra et al. 2014), the “taper tantrum” of 2013 tended to hit

emerging markets indiscriminately (Eichengreen and Gupta 2013) and, in some

cases, countries with better policy frameworks saw relatively larger outflows

as these economies also tend to have the most liquid, easily exited markets.

Looking at earlier rounds of Fed tightening, Joseph Capurso (2014) notes the

collateral damage on emerging markets is often most intense about one year

after Fed policy has been made less accommodative, particularly in countries with

large current-account deficits and banking systems particularly dependent on

foreign wholesale financing. The Institute of International Finance’s (IIF’s)

models anticipate three or four emerging-markets crises each year in which the

US Fed tightens monetary policy, up from the 40-year average of 1.7 crises each

year (IIF 2015). The BIS (2014b) has already sounded warnings about the impact

of higher US yields and a stronger dollar on global debt stocks. In March 2015,

the IMF’s managing director, Christine Lagarde (2015b), cautioned that the 2013

tantrum was not a one-off episode and called on both advanced and emerging

economies to get prepared for increased volatility ahead.

Solving the

financing problems of emerging markets ultimately requires better domestic

policy regimes to win the confidence of their own investors: improvements in

debt restructuring systems deal with symptoms rather than the root causes of

sovereign debt distress. Over long spans, the world’s main concern shouldn’t be

temporary pullbacks during yield increases in the United States, but rather the

secular tendency for capital to flow in the wrong direction between advanced

and emerging economies: more capital consistently heads out of emerging markets

than into them. Rather than a home bias, emerging-market public investors, in

particular sovereign wealth funds and central bank reserve managers, tend to

maintain a foreign bias that goes hand-in-hand with the ongoing stain of

“original sin,” the inability of many emerging-market sovereigns to borrow

domestically or abroad over long tenors at fixed rates in their own currency

(Eichengreen, Hausmann and Panizza 2002; 2007).

Capurso (2014) notes that

emerging market public investors’ assets under management rose from US$3

trillion in 2007 to US$11 trillion in 2012, with most of this devoted to

advanced economies. The roughly US$8 trillion in flows from emerging markets to

advanced economies allocated by emerging market asset managers from 2007 to

2012 was about 10 times greater than the US$0.8 trillion in developed-market

flows pushed by the search for yield into emerging markets during this

five-year span. Any improvement in sovereign debt restructuring regimes should,

therefore, be accompanied by better ongoing domestic economic policy making in

emerging markets, rather than continued pressure on the IMF to endorse capital

controls (IMF 2011a; 2012a).

About The Authors:

Richard Gitlin

joined the Centre for International Governance Innovation (CIGI) as a senior

fellow in June 2013. He played a leading role in the development of practices

and procedures for successfully resolving complex global restructuring and

insolvency cases. Richard has served as adviser to several countries regarding

the modernization of their insolvency laws, including Canada, Korea, Indonesia,

Mexico and the United States, as well as the International Monetary Fund (IMF)

in connection with corporate and sovereign restructuring reform.

Brett House is a

senior fellow at the Jeanne Sauvé Foundation and a visiting scholar at Massey

College, University of Toronto. He is also an adviser at Tau Investment

Management, a startup impact fund. This special report was initiated during his

tenure as a senior fellow at CIGI.

Publication Details:

This work is an

extract from "JUST ENOUGH, JUST IN TIME Improving Sovereign Debt Restructuring

for Creditors, Debtors and Citizens" (Special Report) by Richard Gitlin and

Brett House. Download the Report - LINK

This work is

licensed by the Original Publisher – Center for International Governance and

Innovation, under a Creative Commons Attribution — Non-commercial — No

Derivatives License. To view this license, visit (www.creativecommons.org/

licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/).