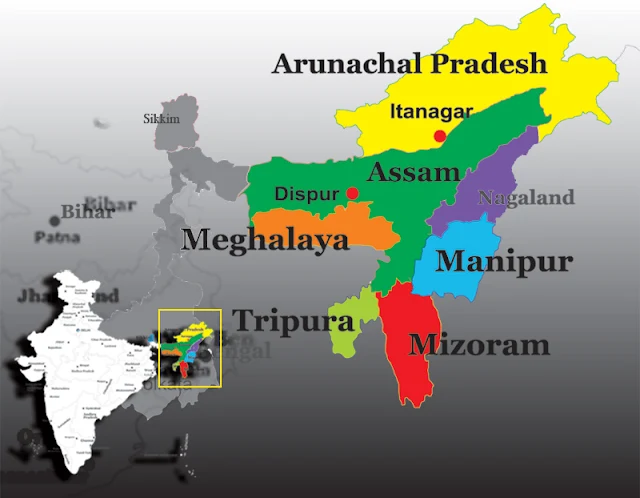

The paper is an attempt to examine the emergence of insurgency movements, the nature of contextualization insurgency activities and spatial conflict in Northeast India in the backdrop of the contesting state power relation.

By Leishipem

Khamrang

Abstract

Northeast India

has been plagued by insurgency related violence and conflicts for many decades.

The greater threat and concern have been, however, the rising regional tensions

albeit promulgation of series of insurgency crack-down policies by successive central

and state governments since the 1950s. To contain insurgency activities, new

winning formulas have been announced occasionally, promising incentives or job

to the surrenderees, with events of surrendering insurgent’s ceremonies yet

several newer insurgents and splinter groups have been formed. The volatile

state power relations intrigue the entire geopolitical condition and create

space for development of newer geographical landscape of conflict thereby

turning the region to one of the most sensitive regions in India. The paper is

an attempt to examine the emergence of insurgency movements, the nature of

contextualization insurgency activities and spatial conflict in Northeast India

in the backdrop of the contesting state power relation.

Keywords: Ethno-Nationalism,

Northeast India, Insurgency, Spatial Conflict, Violence

1. Introduction

Violence and

conflict have been a traditional theme within political geography and

geographers have been consistently arguing that violence and conflict,

including insurgencies, are inherently geographic as they occur in particular

place [1] and across geographical territory. Territories in

Northeast India are demarcated by contradictory superimposed boundaries―modern

state boundaries over traditional boundaries. Historically, traditional

boundaries coincide with the ethnic mapping. Such ethnic territorial identity

has been blatantly ignored during the reorganization of states in the post

independence. Territorial politics, revolving round between these two entities

―modern and traditional boundaries, compound regional conflict with many ethnic

groups asserted to restore the traditional boundaries; the case of Naga

represents an appropriate example. Nagas are one, therefore, construct of

sub-naga identity, such as, Manipur Nagas, Nagaland Nagas, Assam Nagas etc.,

within the federal set up, and Constitution of India is vehemently opposed by

the Nagas. Division of Naga inhabited areas into different states of India is

merely a scheme inducted to neutralize the Naga movements for

independence―movement that was begun before the independence of India. In the

last few decades, new trends of conflict have emerged following the intrusion

of neoliberalism undermining the effective indigenous mode of production. The

problems of the regions are no longer of conventional social and economic

practices but inherently link to the modern statist version of development

policies initiated. The statist version of development policies restructures

the organic relation of the community, dissociates them from the conventional

material practices and gradually pushes them into the unfamiliar new economic

system. The material practices of communities are systematically getting

exposed to a process of contrasting imagination constructed by the state

through projects of neo-liberal capitalist territorialization. The capitalist

and the statist logics are, therefore, found overextending themselves to

subjugate the organic practices from below [2]

thereby creating newer spaces of conflict continually. The contesting state

power relation thus becomes inherently a factor of spatial conflict. The state

deploys military force in an attempt to overawe native opponents, but for the

native who cannot accept state policy, insurgency became the politics of last

resort [3] . It is quite comprehensible that the underlying causes

of conflicts and insurrection of armed insurgent in the region are

intrinsically linked to Central’s apathy towards the unique traditional socio-

economic and political system of varied indigenous communities, and lack of

understanding, recognition and acceptance of mainland Indian to the people of

the region. This is often contested by the statist agents who asserted

underdevelopment and isolation of the region as a result of insurgent

activities and persistent internal ethnic conflicts. However, failure to

integrate the region with the mainland, socially, politically and economically

during the last 60 years of the plan period substantiates the fact that the

problem of the region cannot be viewed from the mainland Indian

perspective―which often negates the indigenous development praxis. The whole

development scenario thus creates space for significant debate which demands

for proper understanding of the societies at the grassroots. The present paper

embarks mainly on understanding the causes underpinning the dichotomy of state

power relation and resulted fragmented space of conflict.

2. Free India

and the Birth of Insurgent Movements in Northeast India

Insurgency is

not a new phenomenon in the history of mankind while in India it emerged mainly

during the 1950s following consolidation, by consent or force, of several

erstwhile princely states into modern India. India in its entire history, until

colonized by the British and united at gun point, was never a single nation [4]

. After the colonial rule, India succeeded in consolidation of many regions and

provinces yet failed to conquer the hearts of many people particularly in the

Northeast. India could conquer the land but not the hearts of the people. For

the people of this region, range from small fiefdoms to large princely states

and who had for centuries enjoyed independent existence, this administrative

and political amalgam amounted to loss of identity and freedom. Besides, the

new dispensation―democracy, in many cases brought no political or economic

advantage [4] . The post Independence era thus opened new chapter of

armed insurgents in the history of India.

Insurgency

activities in Northeast India grew out of varied reasons and purposes with each

of them having different agendas but a single thread runs through them all is

the construction of homeland. Unlike other insurgent groups in India, the

various insurgency movements in Northeast established basic ingredients for

continued insurrection, namely, territorial and community-based group. These

groups are armed, politically as well as militarily organized, while some of

the movements are politically oriented towards the overthrow of present

government. Emergence of such “groups politico-territorial identities” vying

for separate territory within or outside India [5]

has escalated regional conflict. Since most of these insurgent groups are

territorial and community based-group, civil societies and insurgents together

challenge the construct of Indian nationhood taking the pre-independent era as

reference period where many parts of the region were independent under

different form of governances. The tribal communities have their own form of

governance (republic) while the valley dwellers like the Ahom, Kacharis, Meitei

etc., are known for well-established kingdoms under monarchy system [6]

. The term secessionist movement labeled against them is therefore discarded

outright by many and asserted their movements as legitimate―to restore the lost

territory which they held before the advent of the British.

The continued

mass based insurgents grow stronger while some of the frontal civil

organizations are even labeled as mouth piece of insurgents group. Civil

organizations and insurgents are literally two sides of the same coin, merely

existing in different form with different responsibilities, having common goal

of reconstruction of homeland. Historically speaking, many insurgent activities

in the regions starts off as a resistance movement - which is an organized

effort by some portion of the civil population to resist the legally

established government or the occupying power to disrupt the civil order and

stability [7] . Insurgents cannot exist without support of the people.

Insurgency activities, therefore, still remain active in Northeast in spite of

several efforts accorded by Central government to stabilize the situation. Even

deployment of several paramilitary military forces under the provision of Armed

Special Power Act could not subdue the problems in the last 65 years.

Ethnic groups in

the region are bonded by their socio-cultural and political entity therefore

any external forces that disturb this cultural cohesion is bound to have severe

repercussion. Apparently, unimaginative states’ responses have intensified

regional tensions as experienced since the 1950s and against this backdrop,

several armed resistance movements have been given birth. This was the period

when armed insurrection emerged in Nagaland, using the remnant weapons of the

Second World War. The battle at Kohima, fought between the British and Japanese

forces, may be considered as the last battle of the allied forces in Indian

soil but it opened the new path of armed insurrection in Nagaland. During the

Second World War, insurgents and guerilla movements were established with the

support of allied forces in Asia, North Africa and continental Europe while

armed insurrection as a mean of political change was legitimized [8]

. Involvement of allied forces may not be very relevant as far as the birth of

insurgent in Northeast India is concerned. However, one cannot undermine how

the father of Naga Nation: Zaphu Phizo and his brother Kevi Yalley joined

Bose’s INA to fight against the British with a hope that Naga Hills would be a

free nation after the British left India. Severe battle took place at Kohima

between Japanese division supported by thousands of Bose’s INA troops and the

British army. At the end of the war, Phizo was arrested by the British in

Rangoon and served for seven months imprisonment when Rangoon was captured in

May 1944. On his returned to Nagaland, he propagated for free Nagaland. Since

then, the geopolitics of the Northeast took a new turns.

The beginning of

Independence era took a new turn in Indian history with many armed rebellion

groups rose against the state. Interestingly, one of the last conquered tracts

of the colonial regime (Naga Hills) emerged as a place where the first armed

rebellion group was formed in the sub-continent. In fact nationalism is not

recent development; the Ahoms, who ruled Assam for several centuries, fought

back the invading Mughals. The Manikya Kings of Tripura fought the Bengal

Sultans back from the hill region and conquered eastern Bengal. The Burmese

were the only ones who overran Assam and Manipur [9]

. The Nagas and the Lushais resisted strongly against intrusion of the British

into their territories and many British were got killed. The idea of resistance

continued even during the colonial regime. The Nupilan (Women’s war in Manipur)

in 1904, the Kuki rebellion of 1917-1919, uprising of Zeliangrong under the

leadership of Haipaou Jadanong in the 1920s, formation of Naga Club, etc., are

significant markers of resistance movement. After Independence of India,

central’s attitude towards these resistance groups changed, giving emphasis on

complete annihilation of the separatist movements with the military might.

British’s military policy, “Armed Special Power Act” to quell quite India

movement, was therefore reinforced in Northeast India but during these 65 years

long of military regime, several number of insurgency groups have been formed,

putting the success story of military rule under severe criticism from the

civil societies.

3. National

Consciousness and the Rise of Sub-Nationalist Movement―State Wise Scenario

The rise of

sub-nationalist movements and increased socio-political self-assertion by the

minority communities has generated waves of unprecedented violence and conflict

in the region. The birth of insurgency in Northeast India is a manifestation of

revitalization of historical construct of a nation prevailed prior to the

establishment of colonial regime. The Nagas were the first to challenge the

India nationhood in the post independence. Naga nationalism is as old as the

history of Nagas. Naga had resisted against intrusion of several forces at

different point of times in the past even before the advent of the colonial

rulers. The construct of Pan-Naga nation evolved out of political, territorial

and social consciousness which eventually led to the formation of Naga club in

1918. This was a significant event in the history of Naga resistance movement

representing the first organized political movement in Northeast India. The

Naga club submitted a memorandum to the British Simon Commission in 1929

stating that Nagas should be left alone should the British leave India.

Therefore, question of “uprising against constituted Government” does not arise

as a free Indian State had not been then established [10]

.

The construct of

Naga nationalism and Naga identity grew stronger with the formation of Naga

National Council (NNC) in 1946. The Naga National Council was formed as the

representative of Nagas which set out to construct a national identity by

“othering” the Indians [11]

and the organization’s goal was the unification of all Naga tribes [12]

. NNC declared independence of Nagaland on 14th August, 1947

and intimated the same to the Government of India and to the United Nations

Organization. Under the leadership of A.Z. Phizo, NNC gained momentum after

referendum, popularly known as the Naga Plebiscite, was conducted on 16 May,

1951 where 99.9 percent voted for independence of Nagaland. In 1952, the NNC

boycotted India’s first general election and launched civil disobedience

movement; refrained from paying tax to Indian government and set up its own

schools. The situation grew tenser with the movement of NNC become more

radicalized while the India government opted to neutralize the situation with

repressive military measures. Arrest warrant was ordered against the NNC members,

forcing them to take refuge in the jungle. Subsequently, a large number of

Indian Armies were deployed in Naga Hills in 1953 and massive crackdown on NNC

was launched.

Atrocity of

Indian Army was first committed when two villagers (Beechatami and Lopeelu Tami)

were killed and their bodies were tied with ropes and dragged in the street of

Kohima by the police to put fear in the minds of the onlookers in the aftermath

of Nagas leaving en masse few minutes before the delivery of speech by Indian

Prime Minister Jawaharlar Nehru in 1953 at Kohima local ground. This was

followed by massacre of 57 people of Impang village by Pangsha villagers in

Tuensang division of the North East Frontier Agency in 1954. It was found out

later that Indian Intelligence Bureau incited the villagers of Pangsha to

attack Impang village, to avenge the death of one postal worker killed by

Impang villagers. However, the hidden strategy was to eliminate some of the NNC

members encamped at Impang village [13]

. All these incidents did not deter Nagas from their demand for homeland rather

it fueled their angers. Nagas gradually understood the intention and policies

of the Indian government towards the Nagas. Subsequently, NNC declared setting

up of an underground Naga government on September 18, 1954 [13]

. In the early 1955, Makokchung was declared a “disturbed area” and later in

1956 the entire Naga Hills was declared as “disturbed area”. NNC embraced arms

as the last resort to counter the India military might rather surrendering the

rights of the Nagas. On March 22, 1956, NNC formed an underground government

called the Naga Federal Government (NFG) and a Naga Federal Army (NFA) was

created. Since then Northeast India has been passing through insurgencies of

various types and India has been confronting with tenacious insurgency in the

region. The number of outfits multiplied over the years each one with own

agenda.

By 1956, the

NNC’s guerrilla consisted of 5000 men, equipped with traditional spears and

daos as well as weapons left over from World War II [14]

. Without any internal crisis the movement carried on until Shillong Accord was

signed on November 11, 1975 between Indian Government and few signatories from

NNC. The darkest period in the annals of Nagas’ movement for self-determination

came with the signing of Shillong Accord. With the help of Indian Government,

NNC staged a coup and attacked the patriots who denounced the Accord. Those who

upheld the Shillong Accord brought on division amongst Nagas and they are

responsible for fratricide killing [15]

. There were, however, few hardcore nationalists who strongly denounced the

Accord. IsakChishiSwu and ThuingalengMuivah who had established base in

Myanmar-Naga territory since March, 1975 along with the armies who returned

from China did their best to convince A.Z. Phizo and some of their colleagues [16]

. After five years of vain effort to sort out the matter with the then

president of NNC, Mr.A.Z. Phizo, National Socialist Council of Nagaland (NSCN)

was formed with Isak Chisi Swu as Chairman, Thuingaleng Muivah as General

Secretary and S.S Khaplang as Vice President on January 30, 1980. NSCN also

established Government of the People’s Republic of Nagaland. NSCN further split

into two factions in 1988, one faction (NSCN-IM) led by Isak Chishi Swu and

Thuingaleng Muivah and the other faction (NSCN-K) led by S.S. Khaplang.

Government of India entered into ceasefire agreement with NSCN-IM in 1997 and

several rounds of talks have been held without any significant outcome. The

political impasse and lackluster progress in negotiation between the Government

of India and Naga insurgent outfits eventually has compelled some insurgent

leaders to search for more coercive alternative measures having no faith in

political dialogue. Recently, NSCN-K has abrogated ceasefire agreement with the

Government of India and constant threat from NSCN-IM to end the ongoing

ceasefire agreement with the Government of India against futile outcome of

political negotiation places the entire political situation at stake.

In Manipur,

resistance movement against the British first took place in 1904. A popular

movement called Nupi Lan (women’s war) was launched against the oppressive

economic and administrative policies of the colonial power. The first Meitei

armed insurrection was however, started by Hijam Irabot in 1950s against the

merger of Manipur Kingdom with Indian Union on 15 October, 1949. Hijam Irabot

and his fellow revolutionaries formed the “Red Guards” to resist against the

Indian state. Inspired by Marxist ideology which he gained during his prison

life in Sylhet jail, his main aim was to established an Independent Peasant

Republic” in Manipur. However, unable to establish liberated zones inside

Manipur, he went to Burma and secured support from insurgent Communist Party of

Burma. Unfortunately, Irabot died of typhoid at his headquarter in Kabaw Valley

on 26 September 1951 and the first revolutionary movement of the Meitei also

ended after his death [14]

). Armed insurrection reemerged in Manipur when United National Liberation

Front (UNLF) was formed on 24th November 1964. Gradually,

several factions emerged due to leadership and ideological crisis within the

outfit. Apart from UNLF, People’s Liberation Army (PLA) was founded on 25th September

1978, People’s Revolutionary Party of Kangleipak (PREPAK) was set up on October

9, 1977 and the Kangleipak Communist Party (KCP) came into being in April,

1980. Many smaller groups emerged but in spite of indifference in party’s

ideology, restoration of the lost Kingdom of Manipur is their main and common

agenda.

In Assam,

resistance movement against illegal migrants have taken toll of several lives

and displaced several thousands of people. The root cause of today’s problem in

Assam is the local people’s fear psychosis about others [17]

particularly the illegal immigrants. An estimated five million Muslim Bengalis

fled to Assam in the wake of the liberation war in East Pakistan (now

Bangladesh). Sensing the threat to indigenous population of the state, a group

of young men gathered to discuss the state of affairs at Sibsagar’s famous Rang

Ghar (an amphitheatre constructed by the Ahoms three centuries back). The

students began a campaign to expel the state’s millions of foreigners, claiming

that they has stolen job in paper, tea and oil industries. Worse has been the

nexus between the local politician and the illegal migrants where local

politicians helped the foreigners get ration cards and other documents which

made it possible for them to register as voters. Even today, the situation and

practice seem unchanged for wants of vote banks by the politicians. During

Assam violence in July, 2012, L.K. Advani slammed Congress that congress’s

collusion with the massive influx of illegal immigrants from Bangladesh was the

root cause of recurring violence in Assam [18]

. The issue of immigration is the core of conflicts but transformation of such

conflicts into insurgencies with a radical interpretation of their respective

histories, in which the India state is considered as an “external agent” [19]

poses threat to India’s internal and external security. Indeed, the role of

foreign hands has been featured frequent in political debates and India has

been making a significant attempt to accommodate these issues while looking for

economic integration of Asian countries under ambitious Look East Policy.

In the backdrop

of movements against influx of illegal migrants, United Liberation Front of

Asom (ULFA) was formed on 7th April 1979. In addition to the

ULFA insurgency, the largest plains tribes in the State, the Bodos in the 1980s

initiated a movement on issues such as dispossession of their tribal lands by

Bengali and Assamese settlers as well as apathy shown to the Bodo language and

culture by the mainstream Assamese. In 1975, All Bodo Students Union (ABSU)

along Bodo Sahitya Sabha launched movement demanding Roman Script in lieu of

Assamese Script for Bodo language. In the course of movement, 15 persons were

killed and 50,000 Bodo people were arrested [17]

. During the ABSU annual conference between 19th to 22nd December

1988 at Basbari, Bodo People’s Action Committee (BPAC) was formed and decided

to place demand for separate Bodo state. The agitation gradually turned violent

as many youth went underground and formed military organization [17]

called Bodo Security Forces (BdSF). Later, the nomenclature was changed to

National Democratic Front of Bodoland (NDFB). Within the outfit, indifferences

occurred and several splinter groups emerged such as, Bodo Volunteer Force

(BVF), Bodo Liberation Tigers (BLT), People’s Democratic Front (PDF), etc.

Negotiations between the government and the militant outfit culminated to the

creation of the Bodoland Territorial Council (BTC) in December 2003. Apart from

ULFA and the Bodo insurgency, the state has been also affected by insurgent

group of Karbi, Dimasa, the Adivasis and also the Islamists. Karbi and Dimasas

have demanded autonomy for their homelands whereas the Adivasis have demanded

greater recognition of their rights.

Insurgent group

was formed in Mizoram out of resentment against the inadequate and untimely

response accorded by the Assam government during the infamous famine “mautam”

in 1959. In fact the Mizo Hills District Council informed Assam government

about the possible outbreak of famine, following flowering of bamboos, to the

government of Assam, yet the Chief Minister ridiculed the connection between

bamboo flowering, increase in rodents and the consequent famine as tribal

belief [14] . When the tragedy hit, state government could not

response immediately and effectively compelling local people to swing into

action. Large number of voluntary bodies came up to provide relief to the

famine stricken people [20]

. The Mizo Cultural Society, a social club, was converted into a

non-governmental famine relief organization called the Mizo National Famine

Front (MNFF) by Laldenga. Later in 1961, the word “famine” was dropped and the

idea of the organization changed from famine fighting group to independence

movement of Lushai Hills. Many young Mizos were recruited and sent them to

remote villages to distribute the relief supplies and propagate the new slogan:

Mizoram for the Mizos, where Laldenga wanted nothing less than an independent

nation of his people. Taking revolutionary stance to liberate Mizos from the

new Indian regime, MNF embraced arms to rebel against India. To procure arms,

the first batch of MNF volunteers was sent to Chittagong Hill Tracts in East

Pakistan [14). On February 28, 1966, the MNF launched “Operation Jericho”―a

blitzkrieg operation that led to the capture of eleven towns in Mizo hills in

one stroke [21] and declared independent of Mizoram on March 1, 1966.

Laldenga and other sixty signatories signed the declaration, which appealed to

all independent countries to recognize independent Mizoram. The struggle lasted

for 20 years and MNF cadres laid down arms upon signing of the so-called Peace

Accord in 1986, technically termed as “memorandum of settlement” [20]

. Mizoram was curved out from Assam and granted statehood on 20 February1987,

and the outfit leader Laldenga became the first chief minister of the newly

created Mizoram state.

Tripura,

perhaps, is the lone state in India that had tribal kingdom in the history with

more than 1300 years ruled by tribal king before its accession to the union of

India in October 1949 [22]

. The beginning of organized insurgent activity in the late 1970s in the state

was a result of long internal conflict between the illegal immigrants (Bengali

from Bangladesh) and the native Tripuris. The incessant influx of illegal

migrants during the partition caused drastic change in demographic structure,

leading to fierce ethnic conflict ravaged the tiny state for more than three

decades [23] . Between 1947 and 1971, more than 600,000 refugees

entered the state [22]

. The indigenous people in the state, who accounted for 95 per cent of the

population of Tripura in the 1931 census, reduced to just 31 per cent at the

time of the 1991 census [24]

. Large proportion of the immigrants were cultivators resulting to cutting down

of vast forest areas for jhum cultivation. This impacted drastic decline in

jhum land-population ratio, jhum cycle and its productivity. Many of the native

population became landless as their lands were grabbed for rehabilitation for

the immigrants. Tribals were pushed to the hills and gradually immigrants

dominated the politics and administrations in the state. Socio-economic status

of the immigrants also becomes more dominant and tribals were gradually

marginalized. The social and economic consciousness gradually developed among

the educated tribal youths with increasing number of Bengali bureaucrats and economic

marginalization of the tribes. In order to address the educational problems

among the tribals, an organization called Jana Shiksa Samity (JSS), the first

Tripuri (tribal) pro-nationalist organization, was formed by few educated

youths in 1945 [25] . The youth organized themselves under the banner of

Communist Party of India to defend their ancestral land but defected from the

communist party and formed their own party called Upjati Yuba Samiti (Tribal

Youth Party) due to ideological differences. The splinters group subsequently

formed a military organization called “Senkrak” to fight for the tribals right

and injustice meted out to the tribals thus, become the first extremist group

of tribals operating in Tripura [26]

. Since then many new outfits have emerged, such as, Tripura National

Volunteers (TNV), All Tripura People’s Liberation Organization (ATPLO), The

National Liberation Front of Tripura (NLFT), All Tripura Tiger Force (ATTF),

Borok National Council of Tripura (BNCT).

Insurgency in

Meghalaya and Arunachal Pradesh is comparatively recent phenomena. Social,

economic and political consciousness of the native population grew stronger

with the rising domination of non-tribals, resulted to development of

xenophobia amongst the local against the non-tribals. There was a fear among

the major indigenous tribes, i.e., the Khasis, the Jaintias and the Garos,

being swamped demographically, culturally as well as economically by the

non-tribals [27] . Inspired by the logic of “anti-foreigners” agitation

in Assam led by All Assam Students Union (AASU) in the 1970s, Khasi Student

Union (KSU) spearheaded agitation against the non-tribals with the tacit

support of the traditional elites started in the 1980s [28]

. It was against the backdrop of tribal-nontribal dichotomy that insurgency

movement started with a motive of driving out the “dkhars” (outsiders) from the

state. The HynniewtrepAchik Liberation Council (HALC) was formed in 1992 to

safeguard the right of the tribals comprise of Khasi, Jaintia and Garos in

Meghalaya. The outfit split into two factions: Hynniewtrep National Liberation

Council (HNLC), representing the Khasis and the Jaintias, and the Achik Matgrik

Liberation Army (AMLA) representing the Garos. The AMLA subsequently passed

into oblivion to be replaced by the Achik National Volunteers Council (ANVC),

demanding for separate Garo land whereas the HNLC aims at converting Meghalaya

as a province exclusively for the Khasi tribe and free it from “domination” by

the Garo tribe. The only case of indigenous insurgency movement in Arunachal

Pradesh was the rise of the Arunachal Dragon Force (ADF), which was

rechristened as East India Liberation Front (EALF) in 2001. The outfit remained

active in the Lohit district, before being neutralized by the state police

forces. New insurgency outfit called “United People’s Democratic Front” was

floated in 2011, formed by a former member of Dawood Ibrahim gang,

SumonaMunlang [29] . The main objective of the outfit is to create an

autonomous district council (ADC) out of nine circles in Lohit and Changlang

districts of the state. It is believed that the hard-line faction of the ULFA

was playing a key role in the growth of the new outfit [30]

.

4. Territorial

Ideology, Ethno-Nationalism, Homeland and the Bases of Territorialism

“No matter how

barren, no territory is worthless if it is a homeland. Homeland contains the

fundamental of culture and identity; it is special category of territory: it is

not an object to be exchanged but an indivisible attribute of group of identity”

[31]

. This concept encapsulates the entire political movements of different ethnic

groups in Northeast India. The constructs of homeland became popular after the

independence of India, contradictory with each ethnic group attempts to

construct homeland on ethnic line. Contemporary conflicts are deeply rooted in

territorial and ethno-nationalism ideology. Homeland principle is the idea that

people with deep roots and a historical attachment to the land have a right to

control. To the ethnic minority, control over the homeland is vital because it

does not only measure relationship between community and resources but also

cohesive nature of the community where the strength of the community lies.

Increases in territory enhance the power of the community and prove the

possession of power by the community. Reorganization of state and breaking them

into smaller administrative unit is, therefore, considered as abrasion to their

traditional power. They are also apprehensive that losing control of homeland

and territory may result to a loss of capacity to reproduce community identity.

For ethnic group, territory is a defining attribute of their identity,

inseparable from their past and vital to their continued existence as a

distinct group [31] .

The state looks

at territory as indivisible space and often asserts that giving territorial

sovereignty to one ethnic group will set a precedent that encourages other

ethnic groups to demand self-rule [31]

. However, persistence territorial contestation and ethnic conflict are post

independent phenomena arising out of the arbitrary demarcation of state’s

boundaries. After the colonial rule, different territorial entities were lumped

together to form new administrative and political units―or states [4]

without the approval of the people themselves. The territorial/administrative

logic behind the state reorganization and creation of new administrative

unit(s) of modern India, seemingly overrides the traditional concept of

territory, has broken the historical bond of social relations among the

indigenous communities. Redistribution of ethnic population following the

reorganization of states (territories) against the well-defined traditional

territory sowed the seed of contention and territorial conflict. An ethnic

distribution that crosses state boundaries is a source of interstate

territorial conflict [32]

[33]

. For instance, creation of Nagaland state has strong and long repercussions

with many Naga inhabited areas are included in different administrative units

(Assam, Manipur, Nagaland and Arunachal in India and Myanmar). This has

triggered interstate conflict with Naga tribes demanding to bring all the Naga

inhabited areas under one administrative umbrella. Similarly, desire of other

indigenous population to live under unified homeland/territory remains strong

through which their identity can be expressed and within which their mythical

places and spaces are located. The politics of “homeland” under various

sub-nationalist movements, thus, constitutes a central element in the formation

and consolidation of their respective national identities [34]

.

Territorial

politics, revolving around the dichotomy between traditional boundaries (ethnic

boundaries) and modern state boundaries, have intensified regional conflict.

These boundaries remain central to contemporary conflict with each ethnic

community seeks to construct socio-political identity within the traditional

territory associated with ethnic setting. The boundaries may be removed or

altered or functionally changed, but their existence on the ground constitutes

a territorial reality around which political behavior takes place [34]

. The existing modern state boundaries, according to them, are artificial boundaries

drawn arbitrarily against the wishes of the people. Territorial claims are

therefore, invariably couched in terms of recovery of territory that

historically belonged to the claiming state/communities. Eventually, it emerges

as a main source of conflict because the state is fundamentally a place; its

very existence and autonomy are rooted in territory [32]

.

The politics of

territorial identity accompanied by “ethno-nationalism” ideology become popular

in Northeast arguably after the emergence of Naga armed resistance movement.

The birth of Naga separatist movement not only inspired neighboring communities

but also opened the eyes of ethno-political consciousness where “territory”

remains the basis of ethno-nationalism. Subsequently, newer separatist

movements emerged in Manipur, Assam, Mizoram, Tripura and other parts of the

region. The propensity to protect the territory and home community arises

because all the communities are territorial [3]

, occupying contiguous geographical landscape. Such ethno-political

consciousness and assertions made by different communities have made themselves

enemies for one another. Relationship between Meitei and Nagas, Nagas and

Kukis, Assamese and Bodos, Garos and Khasis, Bru and Mizos, etc., remains

uncertain with intermittent conflict being resurfaced. Slogan for restoration

of harmonious coexistence is a far cry with each and every community being busy

in putting up their demands for statehood, autonomy, alternative arrangement,

special status, so on and so forth.

5. Contesting

State Power Relation, Politics of the Dominants and Armed Insurrection

The region is

romantically labeled as the hot bed of extremism or sensitive [17]

infested with varied ethnic armed insurgent groups; range from demanding for

autonomy within the constitution of India to full sovereign nation. There are

varied causes of armed insurrection and conflict: the significant most being

relative deprivation and discontinuous development of the region. These

problems are inherently grounded in the structural policies of the state

inherited from the colonial regime. Such structural policies give rise to

fragmented space characterized by dominant of few core areas leaving the

peripheral in distress. A peripheral region far from the core of a state, combination

of feelings of deprivation is a powerful force that motivates rebellion [35]

. The structural policies, therefore, are perceived as a major source of

grievances and conflicts. The repressive policies introduced to extract

resources increase angers and resistance of the people. Denial of the right to

use conventional politics and protest pushes activists to underground and

spawns terrorist and revolutionary resistance [36]

.

Socio-economic

and political development of the region are inherently tied to the mainland

India through a series of complex relationship reflecting regional dependency.

The economy of the region heavily relies on the import of goods from the

mainland. The syndrome of regional economic dependency and Central’s apathy

towards the region is clearly visible. Regional economic dependency occurs when

one regions’ economy cannot function effectively without sustenance from other

region [37] . Several development programs have been introduced yet

in its journey of transition and development, the experiments in the Northeast

have consistently failed [38]

.

Therefore, the paradox of increasing regional tension and conflict alongside

introduction of newer schemes for regional development has been often

questioned. Relative deprivation, lack of regional integration and

discontinuous development have political and economic repercussion, eventually

generate forces which set the stage of regional conflict [37]

. Failure to integrate with the mainland India politically, economically,

socially and lack of recognition towards the people of Northeast India are the

most fundamental challenges confronted India. The lack of national integration

is rooted in societal divisions, along one or more lines of racial, ethnic,

linguistic, religions. In such situation, it is not surprising to find

intergroup antagonism and distrusts eventually giving rise to insurrections

directed at government [39]

.

Contemporary

spatial development characterized by space of contradiction with varied

socio-political and economic dimensions has gained attention of scholars,

researchers and policy makers. Such contradictory fragmented spaces are created

under new economic system superseding the logic of indigenous mode of

production in the pretext of socio-economic transformation. The negligence of

the Centre towards development of Northeast India is often cited in the

discussion of conflict and underdevelopment of the region. While initiating

development plans, it has been always found that the statist version of

development policies from the Center came as imposed rather instituting

development policies base on the indigenous mode of production. The logic of

indigenous way of development, embedded within the rigid social and culture

practices, in dissonance with statist development policy eventually intensifies

socio-political crisis in Northeast [40]

. This new economic system, exaggeratedly emphasizes on market oriented economy

with assurance of creations of new jobs and reduction in poverty, favors free

enterprises, private capital investment and the extraction of profit from the

poor [41] . Under the new economic system, untapped resources are

systematically exploited in a large scale in the pretext of transforming the

margins, several thousands of poor people are displaced thereby making them

victims of development. Rampant exploitation of resources without generating

benefit to the people who have in fact given up their lands to the corporate coupled

with minimal amount of compensation substantiates powerlessness of the poor

population. Simple statement can be that, the region is not neglected but

people are neglected and victimized in the pursuit of transforming the region.

Negligence by the Centre has resulted to a growing sense of alienation among

the people from the mainstream; manifested in various forms of separatist

movements in the region. Therefore, contrasting tenet of development approach

between the state and the people often resulted to conflict when the latter

attempt to resist the statist version of development [40]

. In this way, the region is doubly displaced within the Constitutional

nation-space: as a political-territorial space of the nation, it is still a

“periphery”, while as a culturally specific locale its difference is unrecognised [42] .

Geographical approach

of conflict emphasizes on the contested power relation. It is a political

violent process through which peoples or groups, who are excluded from power,

contest the ruling authority to alter or replace the existing power

relationship. The geographic approach to power emphasizes the way in which

conflicts and the attempts to resist state power relations are shaped by the

particular context of the places in which they occur and, in turn, how the

politics of power and resistance create particular space and place-specific

politics. In several occasions Nagas in Manipur under the aegis of United Naga

Council (UNC) reiterated to oppose any development project that breaches the

community’s traditional laws and customs. Development projects, such as,

construction of dams, oil exploration, demarcation of Special Economic Zones

(SEZ) etc., are strongly contested through sending memorandums to the Central

government and democratic means. Tribals indeed welcome development programs

but not at the cost of losing their customary and traditional laws of land

management system; land plays significant role in shaping the culture and

ethnic identity. Statist version of development policies often contradicts the

traditional system of land management. Contested power relationship takes

variety of forms; from localized passive non violent resistance against

policies of exclusion to the large scale collective violence of war, which can

be conceived “continuum of violence”, where the contest between dominating and

the resisting power has escalated to the level of insurgency [1]

. Insurgency and its related violence and conflicts in Northeast are

manifestation of such power relationship.

The longstanding

problem of divide between the minority tribals and the dominant non-tribal

group is another major issue in Northeast India. Globally, it has been observed

that ethnic minorities around the world have recently increased political

self-assertion [43] , causing waves of conflicts and violence. The

discontented minority groups consolidate their stance on slogan: distributive

justice against the dictates of the dominant group. The long standing conflicts

between Meitei-tribals in Manipur, Mizo-Chakma in Mizoram, Bengali-tribals in

Tripura etc., provide appropriate example of dominant-minority relation. These

minority groups represent the lower range in the socio-economic strata; often

exploited by the dominant group in employment, education, distribution of

infrastructure facilities etc. The reactions and counter reactions are severe

with often protest by the minority turned violence. In Manipur, United Naga

Council (UNC) has severed all ties with the Government of Manipur and demanding

for “alternative arrangement”. The issues that underlie these conflicts are

diverse but clearly tied to the ethnic setting. In general, history of peaceful

coexistence of the region is gradually fading away with every community

attempts to articulate ethno-political and socio-economic issues on ethnic

line. Even the intellectuals and scholars are divided on ethnic line; each

tries to justify and see the historical construct of the nation (community)

through the lens of their respective historical accounts. Under this

hegemonistic regime of the dominant, the oppressed and minority communities

opted armed insurrection as the only means to assert their rights.

6. Conclusion

The underlying

problems, as discussed, in Northeast India have complex and multifaceted

dimensions including socio-economic and political aspects. The long standing

conflict and violence and the mushrooming newer armed insurrection groups in

the region reflect inability of the state to formulate convincing policies. In

order to alleviate the problems, it is important to understand the relative

deprivation, justification of political action and the balance between

discontented people’s capacity to act and the government’s capacity to redress

the plight of the rebellions [36]

. The prevailing regional crisis and the measures adopted to alleviate the

problems need to be relooked, restructured and reformulated, to promote the

practices that serve best for the community. Development from within, through

incorporation of the old-age indigenous mode of production in the structural

policies, can bring real development in the region. The people feel injustice

and treated step motherly comparing with other groups because they are deprived

from development benefit. To understand the grievances, it is important to

understand ethnicity, culture, political identities of the people and their

position in the society. The point is with whom the people identify and in what

circumstances does a particular identity become more or less salient to them.

The Central’s attitude towards the region is equally important since, in many

cases, Government- imposed policies are a major source of grievances and

conflicts. How government responds to the political action or the grievances,

from which it springs, remain important questions. While seeking to understand

and respond to popular discontents, it is therefore important to examine the

group identities and grievances of the disadvantaged people, including the

poor, unemployed, religious and ethnic minorities; understand the source of

people grievances by examining their status and their treatment by government

and other groups who are more advanced. It is also important to know whether

government policies increase or decrease the potential of disruptive conflict;

important to study the motives and strategies of government in dealing with

disadvantages groups [36]

. Government indeed needs to open people’s participation for such groups.

About The Author:

Leishipem Khamrang, Royal Thimphu College, Thimphu, Bhutan

Cite this paper

LeishipemKhamrang,

(2015) Geography of Insurgency—Contextualization of Ethno-Nationalism in Northeast

India. Open Journal of Social Sciences,03,103-113. doi: 10.4236/jss.2015.36017

Publication Details:

Copyright © 2015

by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is

licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

References:

- 1. Lohman, A.D. and Flint, C. (2010) The

Geography of Insurgency. Geography Compass, 4, 1154-1156. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-8198.2010.00361.x

- 2. Banerjee-Guha, S. (2011) Contemporary

Globalization and the Politics of Space. Economic and Political Weekly,

46, 41-44.

- 3. Polk, R.W. (2007) Violent Politics. A History

of Insurgency, Terrorism and Guerrilla Warfare. Hay House Publishers India,

New Delhi.

- 4. Siddiqi, S.R. (2010) Insurgency Movements in

India. Failure of the Indian Government to Address the Root Causes Could

Lead to a Domino Effect in South Asia.

http://axisoflogic.com/artman/publish/Article_61885.shtml

- 5. Ahmad, R. (2009) Contesting Geo-Bodies and

Rise of Sub-Nationalism in Northeast India: A Case of Nagas and Khasi.

Ph.D. Dissertation, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi.

- 6. Kamei, G. (2011) Feudalism in Pre-Colonial

Manipur. Dialogue, 12.

http://www.asthabharati.org/Dia_Jan%20011/gang.htm

- 7. Scheafer, W. (n.d.) The Economics of

Insurgencies: A Framework for Analyzing Contemporary Insurgency Movements

with a Focus on Exposing Economic Vulnerability. iSites-Harvard

University, Research Paper.

- 8. McColl, R.A. (1969) The Insurgent State:

Territorial Bases of Revolution. Annals of the Association of American

Geographers, 59, 613-631. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8306.1969.tb01803.x

- 9. Bhaumik, S. (2009) Troubled Periphery: Crisis

of Indian’s Northeast. Sage Publication, New Delhi. http://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9788132104797

- 10. Shimray, T. (2005) Let Freedom Ring: Story of

Naga Nationalism. Promilla & Company Publishers, New Delhi.

- 11. Nag, S. (2013) Expanding Imagination: Theory

and Praxis of Naga Nation Making in Post Colonial Period. In: Tanweer, F.,

Ed., Minority Nationalisms in South Asia, South Asian History and Culture,

Routledge, New York, 14-34.

- 12. Chasie, C. and Hazarika, S. (2009) The State

Strikes Back: India and the Naga Insurgency. Policy Studies No. 52, East-

West Center, Washington DC.

- 13. Chandola, H. (2013) The Naga Story, First

Armed Struggle in India. Chicken Neck, New Delhi.

- 14. Lintner, B. (2012) Great Game East. India,

China and the Struggle for Asia’s Most Volatile Frontier. Harper Collins,

New Delhi.

- 15. Welman, F. (2011) Out of Isolation: Exploring

and Forgotten World. HPC Publishers and Distributers, New Delhi.

- 16. Vashum, R. (2000) Nagas’ Right to Self

Determination: An Anthropological Perspective. Mittal Publication, New

Delhi.

- 17. Dev, N. (2009) The Talking Guns, Northeast

India. Manas Publications, New Delhi.

- 18. Bharatiya Janata Party (2012) Assam Riot

2012.

http://www.bjp.org/images/publications/assam_booklet.pdf

- 19. Das, S.K. (2007) Conflict and Peace in

India’s Northeast: The Role of Civil Society. Policies Studies No.42,

East-West Center, Washington DC.

- 20. Pudaite, L. (2005) Mizoram. In: Murayama, M.,

Inoue, K. and Hazarika, S., Eds., Sub-Regional Relations in the Eastern

South Asia: With Special Focus on India’s North Eastern Region, Joint

Research Program Series No.133, 153-240.http://www.ide.go.jp/English/Publish/Download/Jrp/133.html

- 21. Bhaumik, S. (2007) Insurgencies in India’s

Northeast: Conflict Co-Option and Change. Working Paper No.10, East West

Center, Washington DC.

- 22. Gosh, B. (2003) Ethnicity and Insurgency in

Tripura. Sociological Bulletin, 52, 221-242.

- 23. Bhaumik, S. (2012) Tripura: Ethnic Conflict,

Militancy and Counterinsurgency, Policies and Practices—52. Mahanirbam

Calcutta Research Group. http://www.mcrg.ac.in/PP52.pdf

- 24. Phukan, M.D. (2013) Ethnicity, Conflict and

Population Displacement in Northeast India. Journal of Humanities and

Social Science, 1, 91-101.

- 25. Bhattacharyya, H. (1990) Communism,

Nationalism and Tribal Questions in Tripura. Economic and Political

Weekly, 25, 2209-2214.

- 26. Saha, A. (2005) Tripura. In: Murayama, M.,

Inoue, K. and Hazarika, S., Eds., Sub-Regional Relations in the Eastern

South Asia: With Special Focus on India’s North Eastern Region, Joint

Research Program Series No.133, 298-317.http://www.ide.go.jp/English/Publish/Download/Jrp/133.html

- 27. Lyngdoh, C.R. and Gassah, L.S. (2003) Decade

of Inter-Ethnic Tension. Economic and Political Weekly, 38, 5024- 5026.

- 28. Srikanth, H. (2005) Prospects of Liberal

Democracy in Meghalaya: A Study of Civil Society’s Response to KSU-Led

Agitation. Economic and Political Weekly, 40, 3987-3993.

- 29. Mazumdar, P. (2011) Former Dawood Man Forms

Militants Outfit in Arunachal Pradesh. http://www.dnaindia.com/india/report-former-dawood-man-forms-militant-outfit-in-arunachal-pradesh-1627457

- 30. Choudhury, R.D. (2012) ULFA promoting New

Outfit in Arunachal Pradesh.

http://www.assamtribune.com/scripts/detailsnew.asp?id=sep2412/at07

- 31. Toft, M.D. (2005) The Geography of Ethnic

Violence. Identity, Interests and the Indivisibility of Territory.

Princeton University Press, Princeton.

- 32. Murphy, A.B. (1990) Historical Justification

for Territorial Claims. Annals of the Association of American Geographers,

80, 531-548. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8306.1990.tb00316.x

- 33. Murphy, A.B. (2005) Territorial Ideology and

Interstate Conflict Comparative Consideration. In: Flint, C., Ed.,

Geography of War and Peace, Oxford University Press, New York, 281-296.

- 34. Newman, D. (2005) Conflict at the Interface,

the Impact of Boundaries and Borders on Contemporary Ethno-National

Conflict. In: Flint, C., Ed., The Geography of War and Peace, Oxford

University Press, New York, 321-344.

- 35. O’Loughlin, J. (2005) The Political Geography

of Conflict, Civil War in the Hegemonic Shadow. In: Flint, C., Ed., The

Geography of War and Peace, Oxford University Press, New York, 85-109.

- 36. Gurr, T.R. (2011) Why Men Rebel. Paradigm

Publishers, London.

- 37. Bookman, Z.M. (1991) The Political Economy of

Discontinuous Development, Regional Disparities and Inter-Regional

Conflict. Praeger Publishers, New York.

- 38. Bhattacharya, R. (2011) Development

Disparities in Northeast India. Cambridge University Press India, New

Delhi.

- 39. O’Neil, B.E. (2005) Insurgency and Terrorism:

From Revolution to Apocalypse. Potomac Books, Washington DC.

- 40. Khamrang, L. (2013) Contemporary Politics of

Development and Spatial Conflict in Northeast India. Proceedings of the

International Conference Geography of Change: Contemporary Issue in

Development, Environment and Society, Thane, 11-12 January 2013, 153-164.

- 41. Peet, R. (2005) Geography of Power, the

Making of Global Economic Policy. Zed Book, London.

- 42. Biswas, P. (2012) Re-Imagining India’s Northeast: Beyond Territory and State. Journal of North East India Studies, 2, 68-78.

- 43. Yiftachel, O. (1997) The Political Geography

of Ethnic Protest: Nationalism, Deprivation and Regionalism among Arabs in

Israel. Transaction of Institute British Geographer, 22, 91-110.