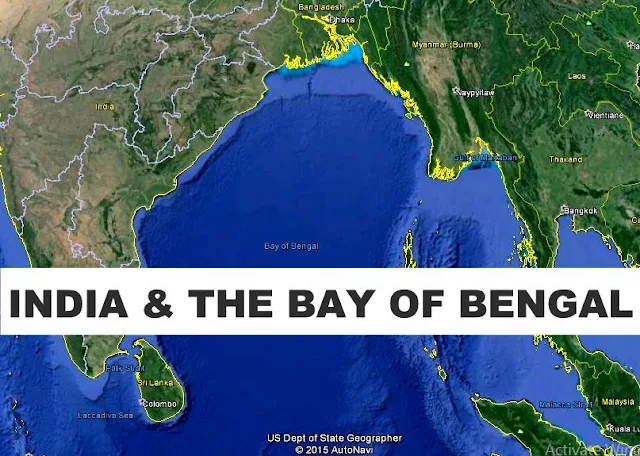

As part of the greater Indian Ocean Region (IOR), the Bay of Bengal (BoB) has historically been regarded as India’s sphere of influence. However, until recently it was treated as backwaters, and it was only after external actors started showing interest in the region that India realized the importance of protecting this geo-strategic area situated right above one of the world’s busiest Sea Lanes of Communications (SLOCs).

By Mohammad Humayun Kabir and Amamah Ahmad

As part of the

greater Indian Ocean Region (IOR), the Bay of Bengal (BoB) has historically been

regarded as India’s sphere of influence. However, until recently it was treated

as backwaters, and it was only after external actors started showing interest

in the region that India realized the importance of protecting this

geo-strategic area situated right above one of the world’s busiest Sea Lanes of Communications (SLOCs).

In terms of

its foreign policy and strategy, India has adopted a ‘Look East’ approach. The

nation is also showing interest in building what it calls the “Bay of Bengal

community”, where it envisages greater security cooperation amongst the

littoral nations. As a result, India may focus on strengthening security ties

with countries like Bangladesh and Myanmar. In other frameworks, such as the

BCIM, the three countries and China are collectively cooperating.

However, this

time, India may opt for cooperation that does not include China as a reaction

to China’s assertiveness in the BoB region. The significance of the BoB to

India’s economy is immense. In 2013, 95% of India’s foreign trade by volume and

75% by value were conducted by sea; and more than 75% of its oil was imported

by sea (Hughes 2014). With India’s economic growth, the importance of its Navy

also grew. As part of its maritime strategy, India states explicitly that it

will strive to ensure the safety of the Ocean’s SLOCs as being critical for

economic growth, for itself and for the global community.

It is also

cognizant of the fact that smaller nations in its neighbourhood, as well as

nations that depend on the waters of the BoB for their trade and energy

supplies, have come to expect that the Indian Navy will ensure stability and tranquility in the waters around its shores (HCSS 2010).

Between 1980

and 2009, the Indian Navy progressed from being a “brown-water” to almost a

“blue-water” force. The country’s economic rise fueled its defence budget and

strengthened its position in the IOR. The Navy is also involved in other

activities such as providing critical training and equipment to numerous Indian

Ocean countries, and its MILAN exercise now includes sixteen Asian and African

navies and coast guards (Samaranayake 2014).

Furthermore,

Prime Minister Modi asserted that he had accorded the highest priority to the

modernization of defence forces, as strong security was necessary for an

atmosphere of peace, amity and harmony in the country. Consequently, India’s

new maritime doctrine includes new policies such as Counter-Terrorism and

Anti-Piracy missions. Since the country cannot match China’s force-for-force,

it needs to seek bilateral alliances, maritime domain awareness, and network-centric

operations. In that regard, enhancing the security of small island states is an

integral part of that strategy (Vines 2012).

An additional

reason behind strengthening its naval power is India’s “Hormuz dilemma”; it

refers to its dependence on imports through the Strait, close to the shores of

Pakistan, where the Chinese are helping the Pakistanis develop deep-water

ports. India’s objectives are hence to gain “strategic autonomy”. This policy

is aligned with the Indian goal of achieving superpower status and it is in

this context that we see India opposing the presence of extra-regional powers

in the BoB and the IOR in general (Stratrisk 2014).

Delhi’s naval

modernization may also be the outcome of a perceived maritime threat posed by

China’s naval growth. In reaction, India is simultaneously developing

relationships with states in Southeast Asia and the Western Pacific, causing

some in China to question its motives. There is fear in Delhi that Beijing may

be outrunning them and strengthening its strategic position in the Bay. China’s

investment in infrastructure and financial aid to the littoral countries could

pose a serious threat to India which, up until now, remained the most important

partner for many of these nations. Now, Delhi is re-focusing on the Bay of

Bengal Initiative through a Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation

(BIMSTEC), with emphasis on improving transport connectivity across the

southern Asian littoral. It is also sponsoring the construction of new road and

river connections between its land-locked northeast states and the BoB through

new port facilities at Sittwe in Myanmar, to be completed by 2015.

Additionally,

Indian officials have welcomed the US re-balancing to Asia but made it clear that

its “Look East Policy” is separate from the US re-balancing and driven by Indian

and not US interests, thus the interests are not synonymous. Nonetheless, a

number of counter-terrorism and anti-piracy efforts have been conducted in

coordination with American forces. US interest in countering the threat of

terrorism in South Asia has pushed India and the United States towards more

substantive military cooperation.

India’s

economic and political links across the BoB are growing, accompanied by an

expansion of India’s regional security role. The nation has long aspired to be

recognized as the predominant power in the BoB and to assume a greater

strategic role in Southeast Asia. These ambitions are consistent with the

perspectives of many ASEAN states which generally perceive India as a positive

factor in the regional balance of power, in contrast with China (Brewster

2014).

The China

Factor:

Historical

mistrust between China and India has encouraged mutual suspicion regarding each

other’s intentions. India and China both view the BoB as a crucial frontier in

their competition over energy resources, shipping lanes, and cultural

influence. The competition stemming from the two countries expanding their

regional sphere of influence in each other’s backyards may result in skirmishes

over energy, SLOCs or maritime issues.

Up until now,

the strongest manifestation of Sino-Indian rivalry in the BoB was in Myanmar

where they both connect through Myanmar to their economically weaker regions,

namely India’s Northeast and China’s Yunnan province. However, since 2011

Myanmar opened its economy to the Western world after the US and Europe lifted

sanctions (BBC 2014), creating more partnership options as the reforms

attracted a wave of foreign investors. This in turn reduced Sino-Indian

competition by making space for new actors and creating more balance in the previously

polarized scenario.

Another major

aspect of the rivalry lies in the so-called String of Pearls Strategy that

China allegedly pursues. However, although there is competition, there is

little evidence that the Chinese are planning an encirclement of India with

their naval facilities stretching from southern China across the Indian Ocean.

Their strategy appears benign, seeking agreements, allowing access to

facilities for resupply, etc. The Chinese are here not for bases but for

access. Bases would involve huge amounts of investment and would have political

implications. It is not just the Chinese Navy that seeks access, the Indian

Navy pursues access facilities too but follows a different strategy from that

of the Chinese. While the Chinese provide aid in infrastructure building, the

Indians create small pockets of bilateral naval exercises (Agnihotri 2014).

In an attempt

to reduce suspicion, China has recently invited India to join the country’s

efforts of building a wide network of new silk roads on land and sea with the

aim of increasing global connectivity (Time of India 2014). Another challenge

for China may be India’s military reaction making Chinese sea lines more vulnerable;

Beijing is already worried about the Malacca dilemma, and now the Andaman and

Nicobar (A&N) Command will put India’s naval and air power in a position to

control access to the Strait of Malacca (McDevitt 2013). Whether it is the US

or India, whoever controls the Strait, will have a stronghold on Beijing’s

energy access, which constitutes a serious concern for China.

About The Authors:

Mohammad Humayun Kabir is Senior Research Director at the Bangladesh

Enterprise Institute in Dhaka, Bangladesh, and head of its Foreign Policy and

Security Studies Division. He studied International Law in Kiev State

University, Ukraine, and International Relations at Oxford University, UK.

Amamah Ahmad is a Research Associate at the Bangladesh Enterprise

Institute in Dhaka, Bangladesh. She graduated with a Bachelor of Arts in Social

Science and a Master of Arts in Political Science from the University of

Lausanne in Switzerland. She has research interests in Geopolitics,

International Security and Transboundary issues.

Publication

Details

Citation

Information: Croatian International Relations Review. Volume 21, Issue 72,

Pages 199–238, ISSN (Online) 1848-5782, DOI: 10.1515/cirr-2015-0007, March 2015.

© 2015. This

work is licensed under the Creative Commons

Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0)

Download The Paper - Link